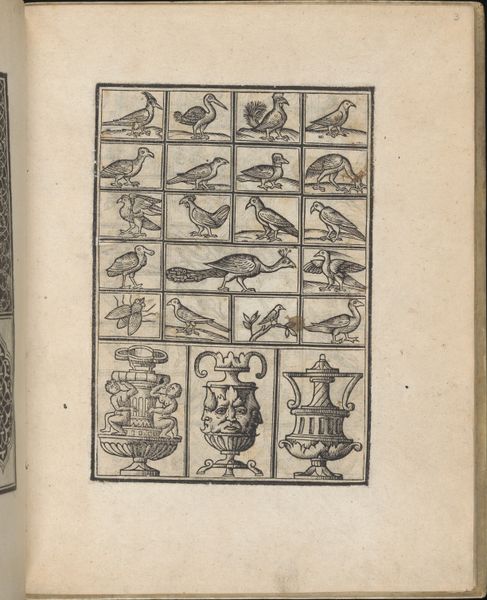

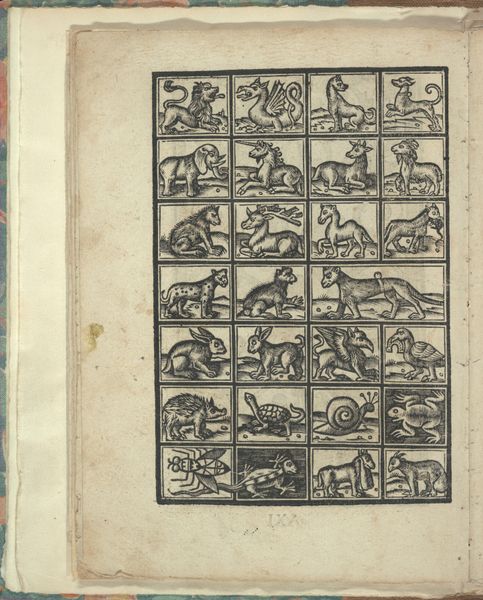

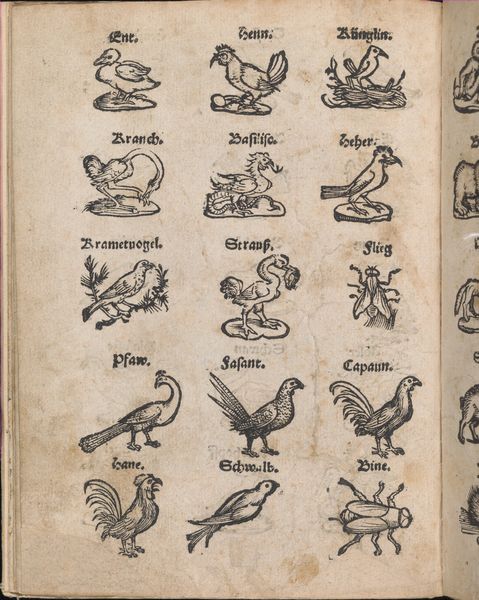

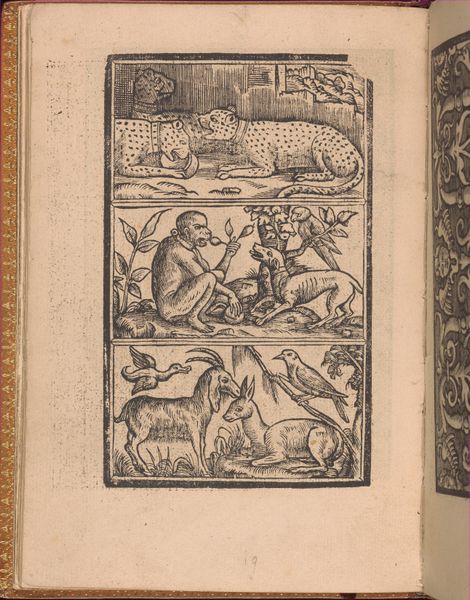

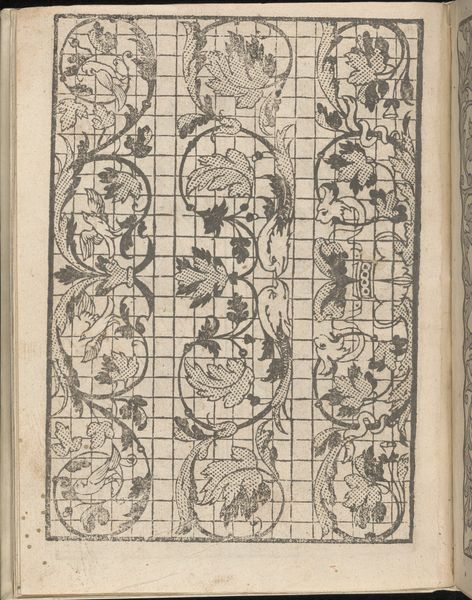

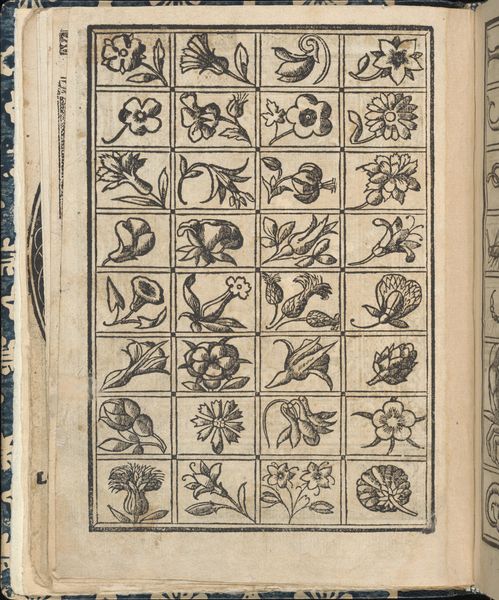

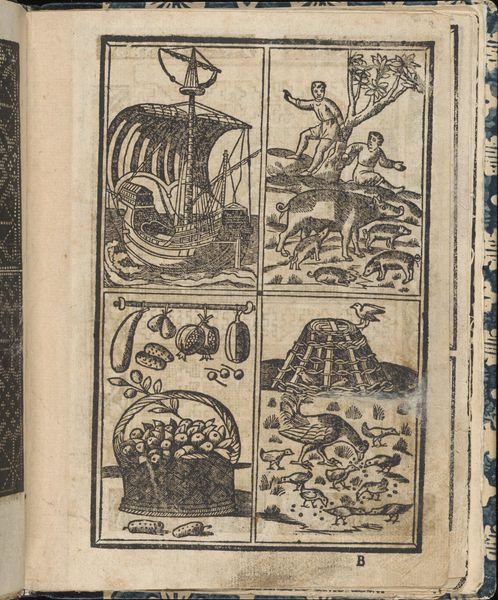

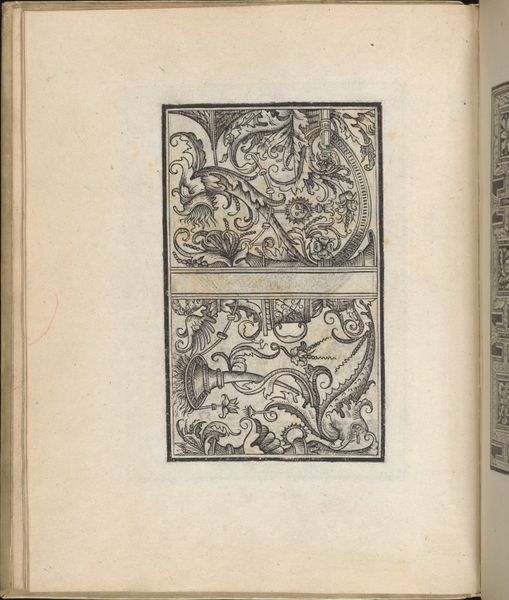

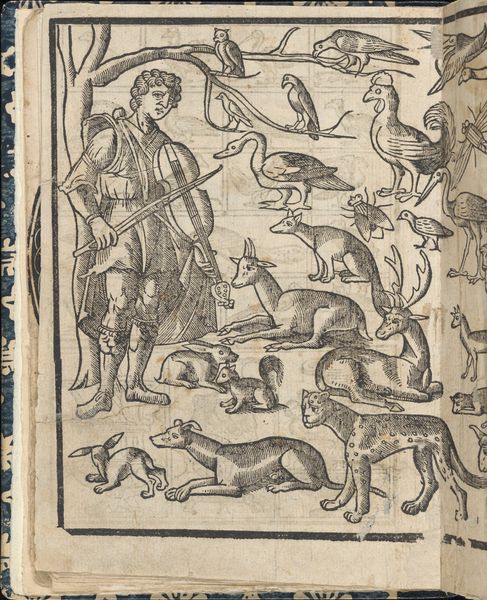

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

#

animal

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

geometric

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: Overall: 7 13/16 x 6 3/16 x 3/8 in. (19.8 x 15.7 x 1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

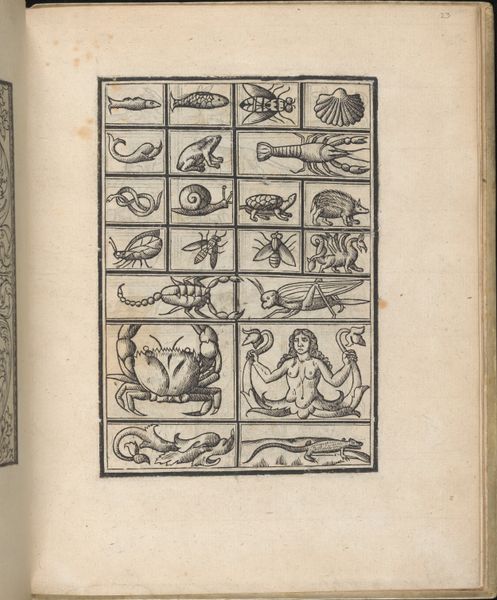

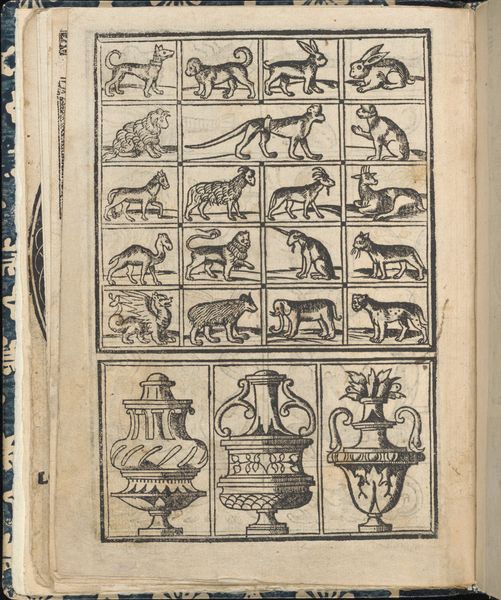

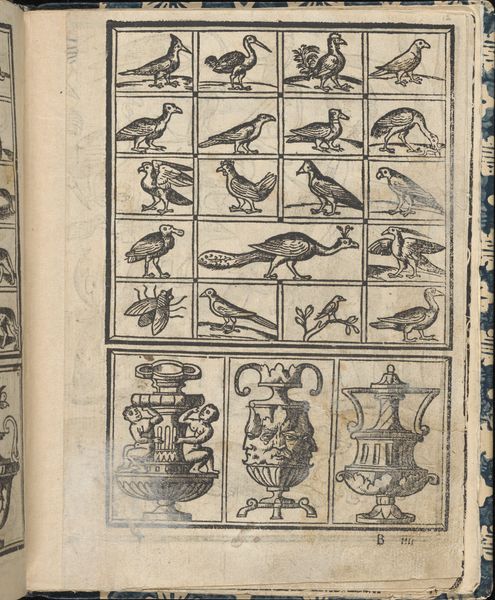

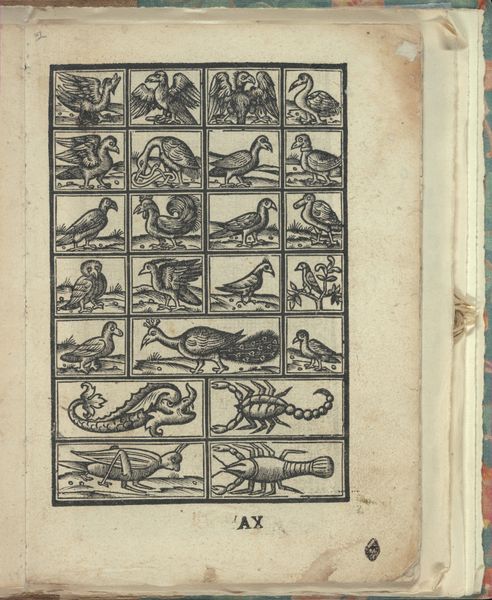

Curator: Here we have "Essempio di recammi, page 11 (recto)" from 1530, made by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente. It's an engraving in ink, presented within the pages of what looks like a pattern book. Editor: What strikes me immediately is its systematic presentation – almost like a natural history compendium, yet filtered through a very decorative, Renaissance lens. It's curious and unsettling simultaneously. Curator: Right, that’s key! These pattern books, specifically "Essempio di recammi", were crucial in disseminating designs throughout workshops. Consider how the very act of producing and reproducing these images using ink and engraving was democratizing design, impacting material culture across different social strata. Editor: Exactly. We should recognize the societal role here. These images – fish, insects, a mermaid! – would then materialize through the labor of embroidery, primarily by women. How did these images intersect with then-contemporary gender roles? Was it about imposing societal constructions of idealized nature, as filtered through gender? The animals here, though decorative, also evoke questions of the known versus the unknown, and the cultural project of categorizing nature itself. Curator: And consider the printing process. The texture of the ink, the pressure of the press on paper…These techniques had direct implications for the artisans replicating the patterns. The book itself becomes a tool and a means of production and control, directing artistic output across a region. It tells us about labor—highly skilled but often invisible labor. Editor: True. When we see the labor manifest – perhaps through embroidery on a sleeve or decorative household object, do we ever consider its connection to the commodification of nature? How far can one extract a design from nature and then transplant it onto another material only to signify one's standing or status in society? I see a complex commentary on the very human impulse to tame nature, literally stitch it onto our world. Curator: Ultimately, a small engraving like this speaks volumes about production, material culture, and artistic circulation in the 16th century. Editor: A stitch in time, as they say, saves not just nine, but a whole history. These images prompt us to ask important questions about design, identity, and social change.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.