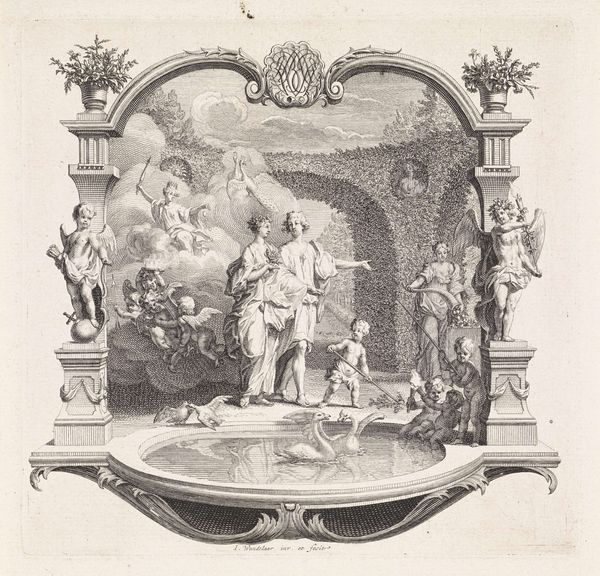

Cul-De-Lamp ad the End of the Volume, Page 91, from Dissertation sur les attributs de Vénus qui a obtenu l'Accessit au judgement de l'Académie Royale des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres à la séance ublique du mois de Novembre 1775. Par M. L'Abbé de La Chau, biliothécaire, secrétaire Interprète et Garde du Cabinet des Pierres gravées de S. A. S. M.gr le Duc d'Orléans. A Paris. de l'Imprimerie de Prault. Imprimeur du Roi quai Gêvres. et se trouve chez Pissot Libraire ru Hurepoix 1776

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Sheet: 4 3/8 × 4 3/4 in. (11.1 × 12 cm) Plate: 4 1/16 × 4 7/16 in. (10.3 × 11.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This engraving, created in 1776 by Augustin de Saint-Aubin, is titled "Cul-De-Lampe at the End of the Volume, Page 91, from Dissertation sur les attributs de Vénus..." Quite a mouthful! It resides here at The Met. Editor: It’s rather delicate. The framing elements almost overwhelm the central figure, Venus, making her feel precious, a jewel enshrined. I’m immediately drawn to the question of accessibility in representations of the female form during this period. Curator: Absolutely, considering this image stems from an academic dissertation on Venus's attributes, we have to acknowledge how these depictions served to define and confine understandings of beauty, desire, and female identity, particularly for elite consumption. Saint-Aubin was a known figure of the French Enlightenment. We might analyze how prints like these bolstered social stratification at that time, commodifying idealized beauty and dictating specific modes of looking. Editor: Looking at the crisp lines achieved by the engraving technique, and how meticulously each flower and drape is rendered, I wonder about the labour involved in its making, and about the cultural value placed upon the image-making craft itself during that moment in French society. The precision demanded in this kind of print production speaks volumes about artisanal specialization. Curator: The neoclassical style and allegorical theme are significant here. These artistic elements are inherently gendered. Think about how classical allusions were manipulated to reinforce specific narratives about gender roles and morality, influencing societal perceptions through the constant circulation of images just like these. Editor: Thinking about consumption, the work must also be situated within a visual economy in which this idealized Venus enters different spaces – whether aristocratic boudoirs, libraries, or the hands of print collectors. In these various spaces it carries meaning that also reflect how the female form can exist between being an everyday consumable and ‘high art’. Curator: I completely agree. The circulation of these kinds of images speaks directly to power dynamics in 18th-century France. Reflecting on our discussion, it reminds us that this image should encourage viewers to examine, critique, and resist narrow representations of gender and identity. Editor: Agreed, the emphasis on craft is really helpful to understand these power structures: material access, technical knowledge, labor, and even this very specialized act of printing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.