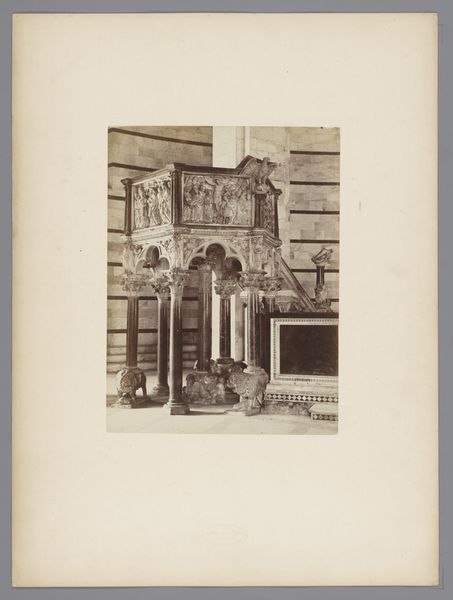

XIVe Station. Le corps de Jésus est deposé dans le tombeau. Monument du St Sépulcre où le corps du Christ a été enseveli. 1860

0:00

0:00

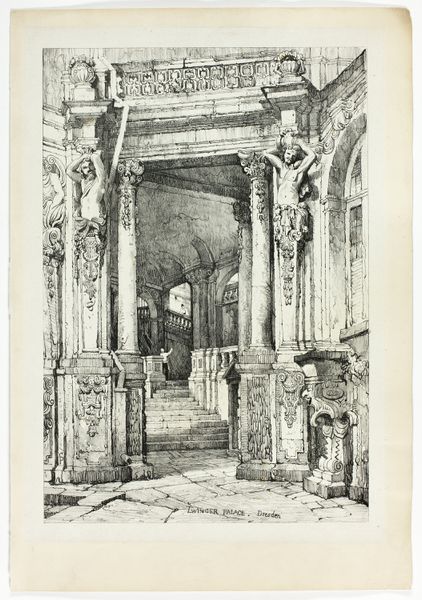

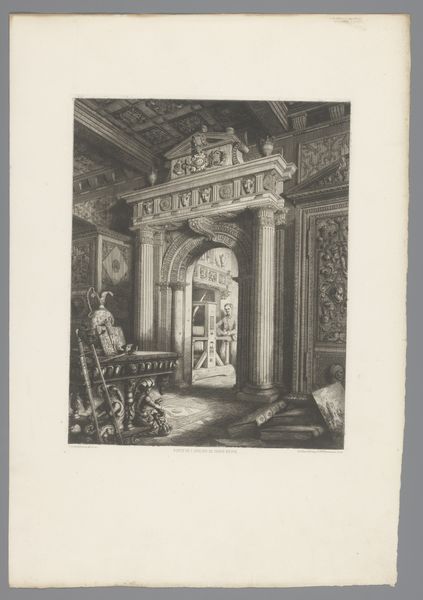

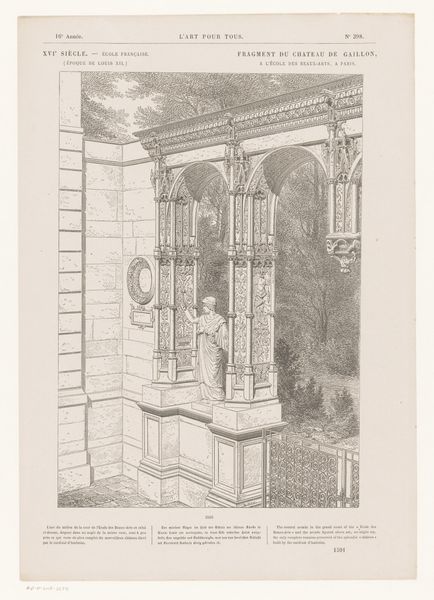

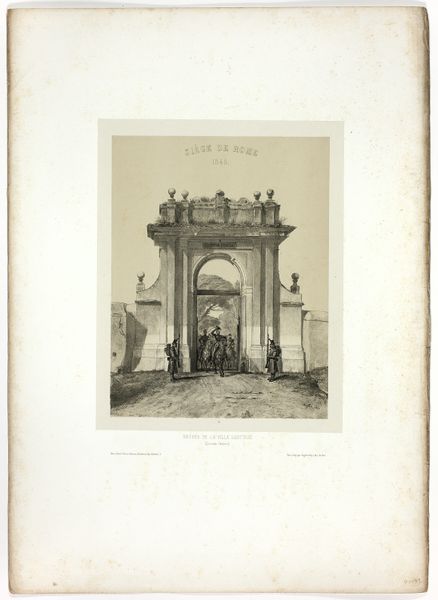

print, engraving, architecture

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 9 5/8 × 7 9/16 in. (24.5 × 19.2 cm) Mount: 17 15/16 × 23 1/4 in. (45.5 × 59 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: It has such a feeling of hushed stillness, doesn't it? That shadowed doorway promising...nothingness. Editor: Yes, that’s the literal and metaphorical point of the Fourteenth Station, the Tomb, illustrated in this engraving by Louis de Clercq. Completed around 1860, it depicts the sepulchre, the place of Christ’s entombment. Curator: Clercq captures a rather specific image here. Is he presenting us with an objective document of religious significance or something more... personal? Editor: I see it as a reflection of its time. Mid-19th century European fascination with the Holy Land created a context. This engraving acted not merely as a devotional piece but engaged in broader dialogues about representation, cultural memory, and even Orientalism. Consider its positionality then. Curator: Interesting. The Stations of the Cross are almost cinematic in how the visual imagery carries the memory, the pain, and then here, the emptiness... The image of the shrouded sepulchre is so weighty with implications. How are the cultural values of this memory upheld when translated through an orientalist lens? Editor: Precisely. Its creation intersected colonial gazes and religious faith. De Clercq’s focus on the sepulchre itself frames a European idea of what this "holy place" is; in so doing, it risks exoticizing it as opposed to conveying the deeper message around justice and mourning the site holds. Also, you could argue that the very act of reproducing religious iconography in this way—through the mechanics of engraving and mass distribution—decentralizes the authority and traditional exclusivity. Curator: I can see that tension, and feel the conflicting emotions conveyed. What do you make of the fact it presents not the resurrection, not ascension but the Tomb itself? It’s so austere, so definitive, and absolute. Editor: By choosing to freeze this specific moment in the narrative of suffering and then resurrection, I wonder, too, if de Clercq is trying to pose difficult questions around loss, legacy and what constitutes faith when it confronts historical complexities and social power dynamics? Curator: So much more to this image than just the literal scene! It makes me ponder the weight of such heavy symbolism across centuries and cultures. Editor: Me too. De Clercq's print encourages viewers to reflect on its history of faith, representation, and the politics that frame both.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.