drawing, paper, ink, pen, engraving

#

drawing

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

pen

#

academic-art

#

engraving

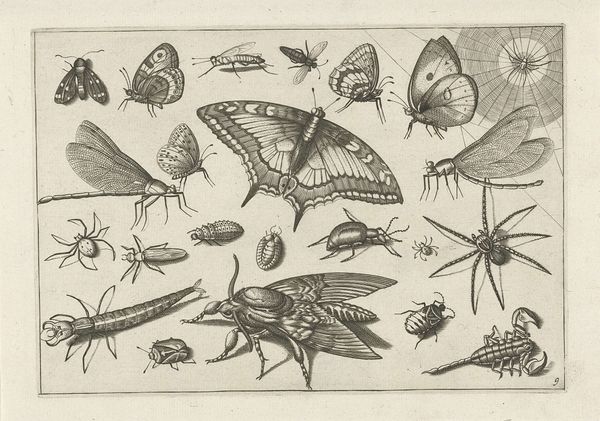

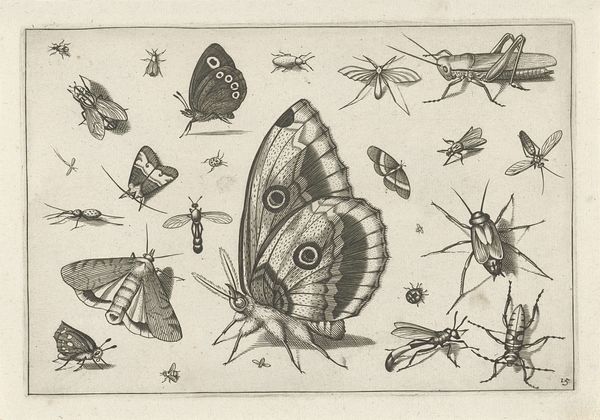

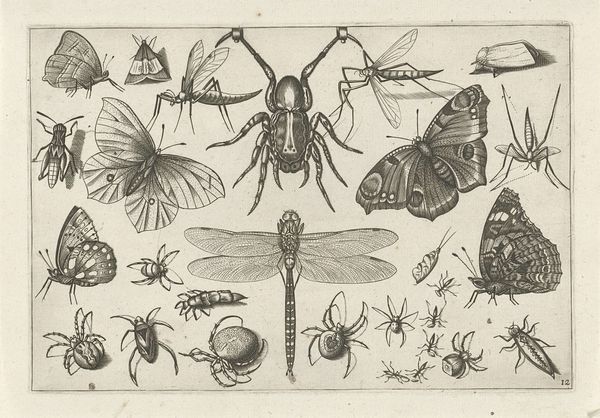

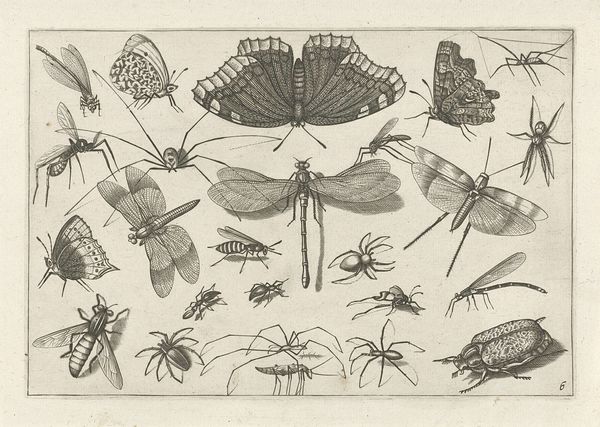

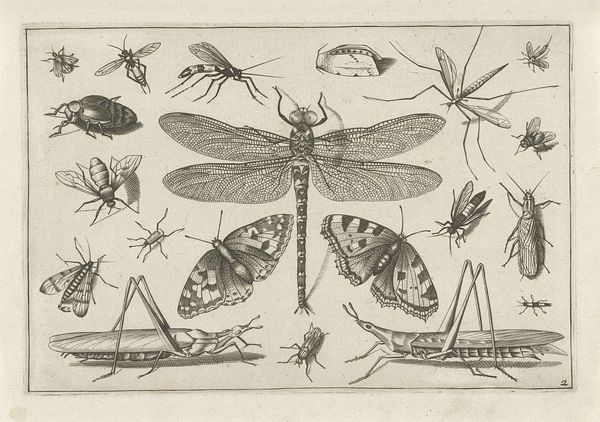

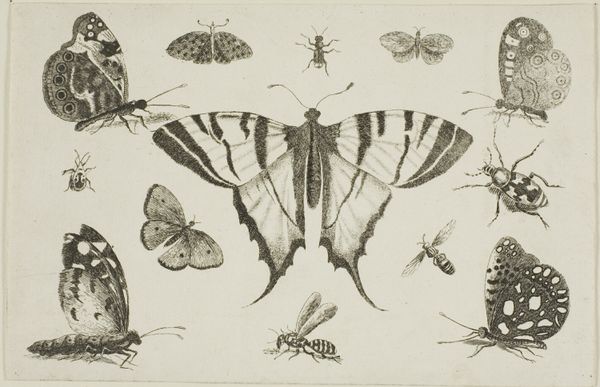

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "Insecten," created around 1630 by Jacob Hoefnagel, what immediately strikes you about this pen, ink, and engraving artwork? Editor: I'm immediately struck by the detail and precision. It feels like a scientific illustration, almost like a collection of specimens laid out for study. There's a clinical quality that separates us from nature's vibrancy. Curator: Yes, the historical context here is crucial. The 17th century was a period of burgeoning scientific exploration, where the natural world was classified, dissected, and visually documented in service of European power structures. "Insecten" must be viewed within the power structures that were emerging, especially pertaining to trade and access to nature’s material wealth. Editor: So, this isn’t simply about observation; it's also about power and possession? I see your point. Even the materials—the ink, paper, and engraving tools—speak to that process of controlled replication. What was accessible? Who owned these objects in the context of emerging capitalism and European empires? Curator: Precisely. Insects, sourced globally and visually preserved as if trophies of European "exploration," came to be presented disembodied from both ecological webs of relationality and the labour involved in their procurement. Hoefnagel was working within an era of shifting material dynamics where the labour practices of obtaining these specimen have come to be replaced by capital’s fetishization of ownership. Editor: And what of the craft? How did Hoefnagel’s specific process impact our reading of the piece? There’s undeniable skill at play here – look at the chitinous sheen rendered by the pen work on the beetles, or the implied delicacy of the butterfly wings. Curator: I believe his training further enabled certain values such as observation and careful collection to solidify themselves within broader culture, setting standards for “objective” natural representation as a service for further ecological degradation in colonized regions of the world. Editor: It’s fascinating to consider that what may seem like a neutral, scientific rendering holds this loaded historical and economic framework. Thinking about art as evidence really alters my interpretation here. Curator: Exactly. And recognizing this artwork within broader intersectional narratives encourages dialogue concerning ongoing colonial practices evident today, so considering that, how has your perception evolved? Editor: It feels less like a record of natural curiosity and more like a symptom of our own history with the environment. Thanks for reshaping how I'll understand not only art from this era, but even approaching what counts as "empirical evidence."

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.