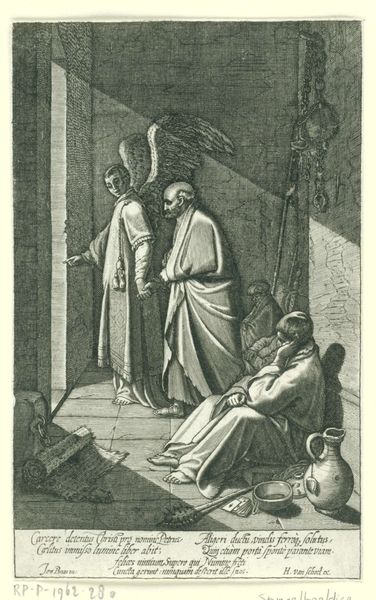

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

sword

Dimensions: height 172 mm, width 108 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to "Petrus en Paulus," an engraving made in 1647 by Gilles Rousselet, currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. What strikes you initially? Editor: There's a gravity to the figures, a somberness. They’re imposing, yet something about the monochrome tones feels understated. Almost contemplative. Curator: The process of engraving itself, the labour involved in transferring such detail to a copper plate and then producing multiple impressions, speaks to the importance afforded to these figures. Consider the physical act of creation and replication for devotional or didactic purposes. Editor: Exactly. And look at how Rousselet presents Peter and Paul, key figures in early Christianity. Peter holds the keys, traditionally symbols of his authority in the Church. Paul leans on a sword, symbolizing his martyrdom, his sacrifice to further the Christian mission and the intersection of faith, power and sacrifice within religious doctrine. Curator: Note the architecture, as well. The rather severe stone structure, also the rendering of cloth. The material support systems surrounding artistic making are a critical point to emphasize: economic patronage systems and distribution chains supporting Rousselet. The printing process suggests access and circulation for such iconographic themes. Editor: Definitely. It makes you think about the intended audience and the cultural function this print would have served back then. These images circulated, disseminating not only religious ideas, but also constructing and reinforcing power dynamics. Peter's keys suggest hierarchy, control, a patriarchal legacy that warrants deconstruction. Curator: Moreover, the quality of paper impacts how such pieces exist materially. Was it intended to be housed among valued materials in collections? Or was it to function more directly, affixed to everyday things? How were these ideas mediated by different degrees of permanence? Editor: It is true—thinking about it materially situates the art in everyday life during that period. I'm really drawn to how the figures embody a complex mix of vulnerability and authority, their presence resonating with both religious power and the heavy cost of faith, especially as those concepts relate to contemporary dialogues around religious authority. Curator: By considering how the means of producing art shapes, supports and distributes certain visual narratives and the lives involved in this network of practice, the viewing can move past appreciation of subject toward understanding its operation within social constructs. Editor: And perhaps that exploration encourages us to re-examine power and its ongoing impact, connecting the historical context with the power imbalances still affecting our present day, urging us to examine and maybe even reshape these power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.