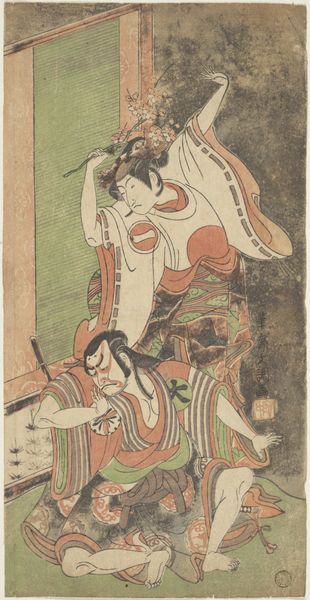

The Actors Nakayama Kojūrō VI as Hatchōtsubute no Kiheiji 1785

0:00

0:00

print, ink, color-on-paper, woodblock-print

#

narrative-art

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

figuration

#

ink

#

color-on-paper

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 15 5/16 × 10 3/16 in. (38.9 × 25.8 cm) (image, sheet, vertical ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: The piece before us, hailing from 1785, is a woodblock print titled "The Actors Nakayama Kôjûrô VI as Hatchôtsubute no Kiheiji" by Torii Kiyonaga, currently housed in the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: Okay, my first thought? Chaos! Controlled chaos, mind you. Everyone looks like they're either about to draw a sword or already mid-lunge. The colors are so bold, and the poses, dramatic. Curator: Yes, it’s certainly arresting. Kiyonaga was a leading artist of ukiyo-e prints, an art form deeply intertwined with the floating world of kabuki theater and the pleasure districts. Prints like this were immensely popular souvenirs and celebrity portraits. The exaggerated features and vibrant colors aren't just aesthetic choices; they signal specific character types and emotional states common in kabuki. Note the stylized cloud that seems to hover menacingly; this visual device often denotes something otherworldly or portentous within the narrative. Editor: Portentous indeed! I am zeroing in on the central figure: the one surrounded by that radiating halo... it’s so striking, almost comical, yet also terrifying. Like a deity mixed with a matinee idol. What’s that all about? Curator: That visual device signals the actor’s role as a character touched by supernatural powers. Radiating halos are common visual tools of stagecraft to distinguish extraordinary figures from the mundane ones, imbuing him with an air of heightened drama and significance within the play's context. The makeup, the exaggerated pose, it's all calculated to project meaning to an audience familiar with the codes and conventions of Kabuki. It represents the cultural memory inherent in performances and rituals, creating resonance for the audience. Editor: Interesting, so it’s like reading a theatrical language. Looking at that reddish figure in the foreground, coiled like a spring—he seems less superhuman, more... primal? And is that really a pink samurai? Is pink code for something, or did the artist just feel like pink that day? Curator: Likely a stylistic flourish, adding dynamism to the overall palette. Ukiyo-e was commercially driven, designed to capture attention and be appealing to a broad audience, even if that meant deviating from strict realism. Each actor, color, or stylized prop on stage carried symbolic weight. It creates a visual language which informs the audience and tells its own stories, echoing and enriching our experiences even today. Editor: Looking at this piece has been really illuminating; I am walking away seeing all those little performative languages which creates a rich, colorful world. It reminds me that what looks spontaneous or random might be deeply coded.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Related to the play Yukimotsu take furisode Genji 雪矯竹振袖源氏, performed at the Nakamura Theater in the 11th lunar month of 1785. This scene is from a Kabuki play based on the historic rivalry between the Taira and Minamoto clans. In 1159, Minamoto no Yoshitomo attempted to overthrow Emperor Nijō, whose regime was bolstered by the warrior Taira no Kiyomori. The coup d’état failed but led to a full- scale war. The play is set in the aftermath of the attempted coup. In the scene illustrated here, four key characters unexpectedly meet in Kyoto’s Gion district. Hatchōtsubute no Kiheiji, a Minamoto warrior who switched his allegiance to the Taira clan, has been living covertly as a monk who fills temple lamps with oil. Played here by Nakamura Kojūrō VI, he is shown holding an oil pot. Minamoto no Yoshihira (son of the coup’s leader, Yoshitomo), played by Ichikawa Yaozō III, has also been living undercover, waiting for an opportunity to again attack the Taira. Here, Yoshihira has recognized the traitor and begins to draw his sword, a magical weapon known as Raiden-maru (Lightning) because its unsheathing causes a thunderclap.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.