Copyright: Public domain

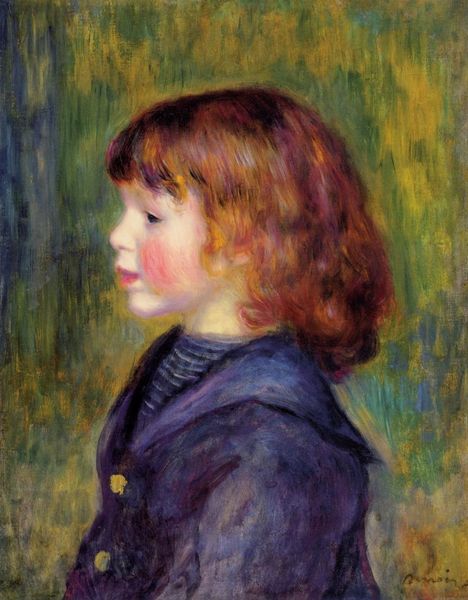

Curator: Here we have Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s “Portrait of a Kid in a Beret,” created around 1892. What strikes you immediately about it? Editor: The color, definitely. That muted palette – sandy browns, earthy greens, the deep blue of the beret and coat… there’s a tangible warmth to it despite the somewhat solemn expression of the boy. The rough canvas texture shows through the paint layers, contributing to its materiality. Curator: Absolutely. The roughness you describe is a key component of Impressionist works made en plein air and serves as the backdrop to interpret childhood within a historical context. It begs the question: who was this boy, and what social forces were shaping his life and identity at the time? His beret and coat hint at a certain class, a boy on the cusp of adolescence shaped by expectations of masculinity and social status. Editor: That’s interesting to think about. My eye goes to how Renoir captures the fall of light on his form and within his surroundings—the way the light shapes his features with broad strokes and visible brushwork, particularly within his cloak and face. We know that Renoir was fascinated with rendering light and texture, with the physicality of paint itself, a way for an industrializing era to push against such advancements, as handmade. How did materials influence our understanding? Curator: That's right, that approach highlights the very act of artistic production, connecting it to labor practices and materiality. Renoir elevates "lowly" subjects to the status of high art. But it’s worth examining the gaze itself. Is there a sense of vulnerability or stoicism being constructed here? What norms around masculinity are being performed and how does it play to the rising industrial environment and notions of work in Europe? Editor: I agree, looking at the gaze is critical here. The lack of direct eye contact gives a candid effect. We understand Renoir’s portraiture focused on moments of everyday life rather than idealized representation. Curator: And in capturing this momentary quality, it makes me think about broader questions surrounding childhood and social conditions, particularly how the weight of tradition, class, and the burgeoning industrial age shaped these nascent identities. It encourages a deeper understanding of what boyhood embodied back then and what echoes we can perceive today in social constructions of identity. Editor: Seeing Renoir handle his materials here adds an extra layer for understanding and valuing the human effort needed to translate these conditions and this child to us. Curator: It does indeed. This offers a way into the study of both material existence and ideological making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.