painting, oil-paint, fresco

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

fresco

#

oil painting

#

chiaroscuro

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

portrait art

Copyright: Public domain

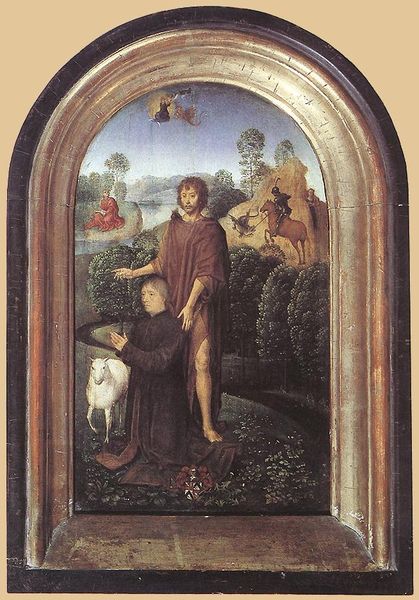

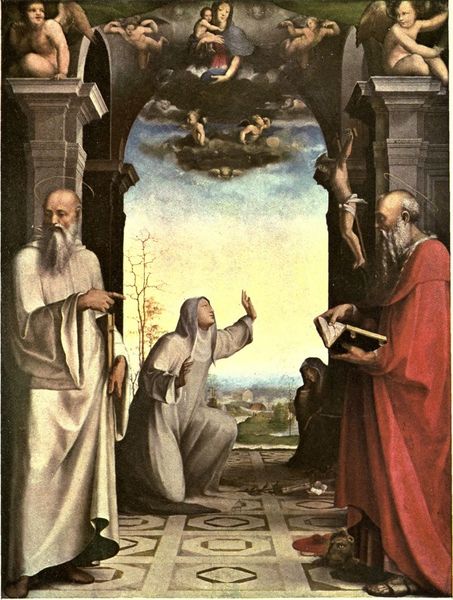

Editor: Here we have Ambrogio Bergognone's "Saint Francois reçoit les stigmates," painted around 1510. The oil paint gives a beautiful, soft quality to the landscape, but those beams of light connecting Saint Francis to the figure of Christ really dominate the composition. It's almost unsettling. What do you see in this piece? Curator: For me, it speaks to the profound empathy at the heart of the Saint Francis narrative. Those beams aren’t just about divine intervention, they’re conduits for understanding, illustrating a lived experience of Christ’s suffering. Notice how Francis's body mirrors Christ's, implying a spiritual and corporeal connection? How do you think Bergognone uses landscape in this context? Editor: Well, it feels very Italian, but also kind of…staged? Like it's there to showcase the event, not to feel like a real place. Curator: Precisely. Bergognone uses the Italian landscape not as mere scenery, but to legitimize and naturalize the religious narrative. The positioning of a built structure, such as a monastery or commune on a hill – like you see in the painting – often signifies control and claims to land. It’s about grounding the divine in a tangible, relatable, and crucially, a *claimed* space. How does that change your interpretation of the scene? Editor: I hadn’t considered the idea of “claiming space,” or ownership. So it’s not just a picture of a religious event, but also a statement about power and control? Curator: Exactly. Early Renaissance art often functions in this way, legitimizing social hierarchies through religious iconography. Considering the historical context—the power of the church, the emergence of humanist thought—the painting operates on multiple levels. The narrative intertwines faith and influence of institutions. Editor: This makes me consider a deeper complexity of the composition and think about the significance of its socio-political underpinnings in Renaissance Italy. Curator: Indeed. It's about viewing the work as embedded in social power relations, not just detached admiration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.