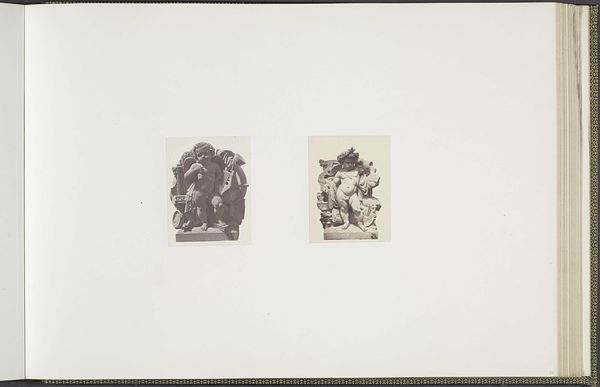

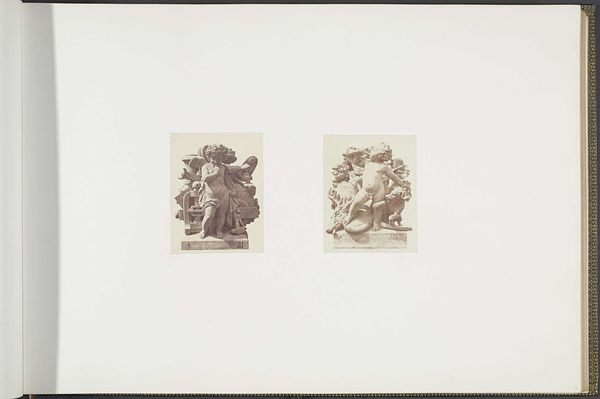

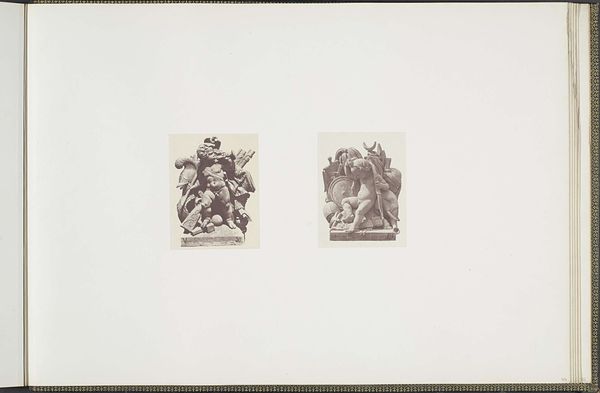

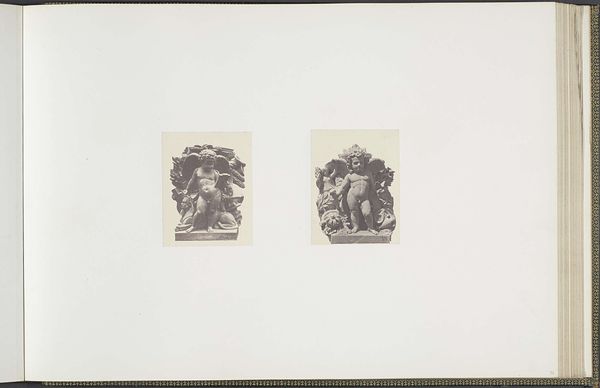

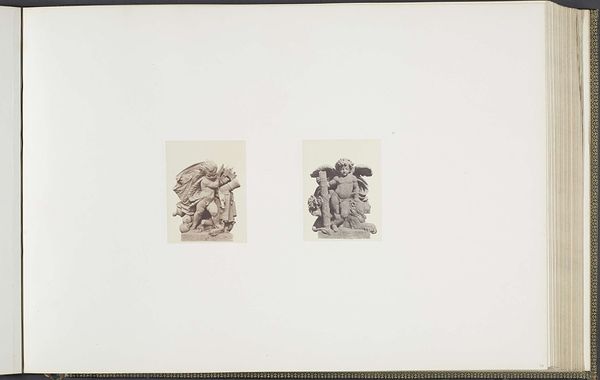

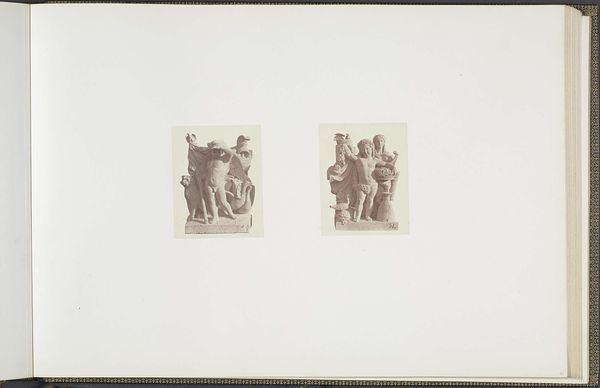

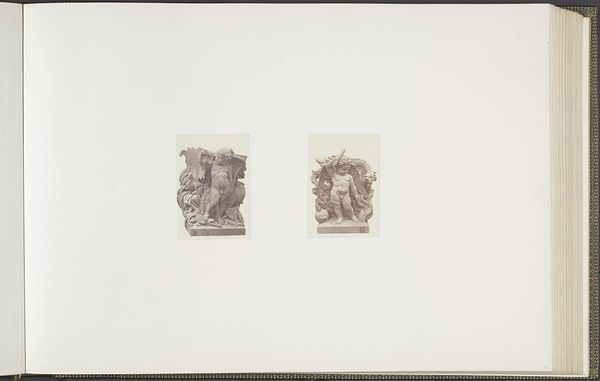

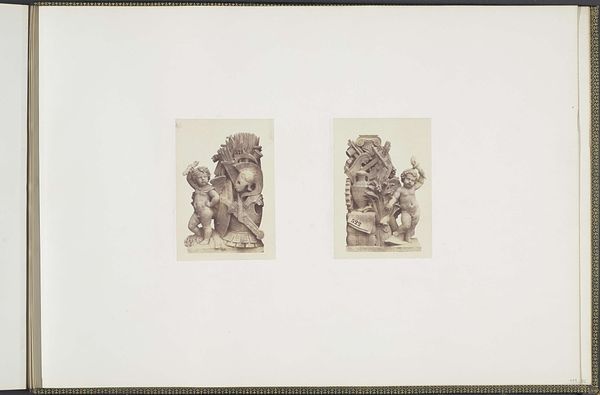

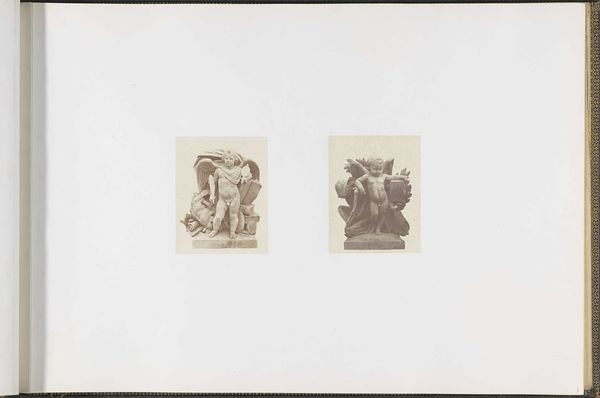

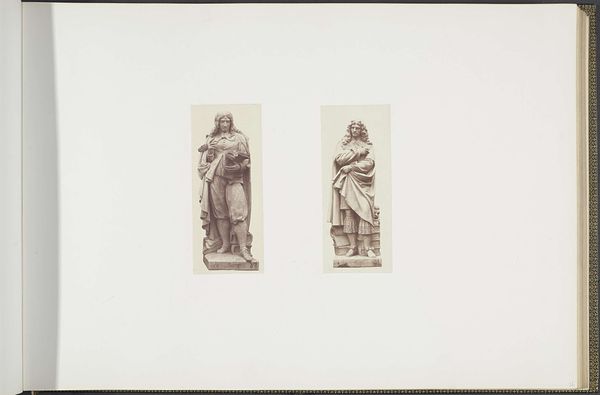

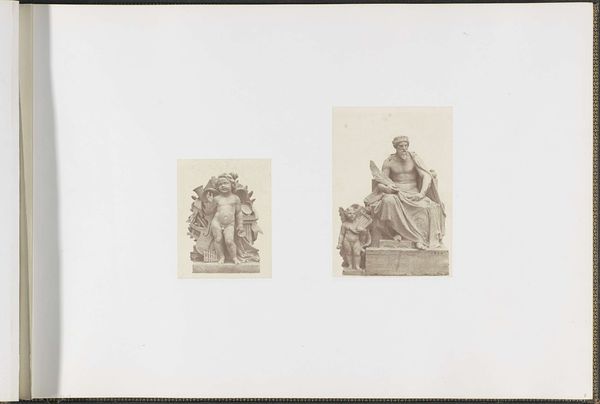

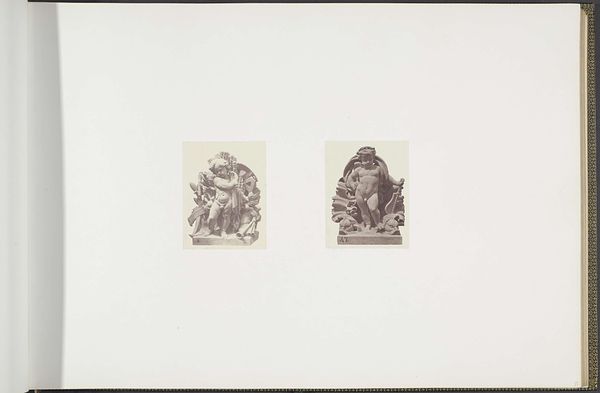

Gipsmodellen voor beeldhouwwerken op het Palais du Louvre: vlnr "La Marine" van Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, "L'Agriculture" door Théodore Gruyère en "Le Commerce" door François Truphème c. 1855 - 1857

0:00

0:00

edouardbaldus

Rijksmuseum

#

photo of handprinted image

#

natural stone pattern

#

toned paper

#

ink paper printed

#

pencil sketch

#

white palette

#

linocut print

#

watercolour illustration

#

tonal art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 378 mm, width 556 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a photograph by Edouard Baldus, taken between 1855 and 1857. It’s called "Gipsmodellen voor beeldhouwwerken op het Palais du Louvre," which translates to "Plaster models for sculptures at the Palais du Louvre." We see three separate sculptural groups, all photographed in the same light and presented together. What strikes me is how these preparatory models, intended to be translated into a monumental scale, are here captured so intimately. How do you read this piece in the context of its time? Curator: This image, beyond being a simple document, speaks volumes about the mid-19th century art world. Baldus, commissioned to document architectural projects, including work at the Louvre, inadvertently reveals the mechanisms behind monumental art. Consider the public role of the Louvre at this time. It wasn’t just a museum, but a statement of French power and cultural ambition under Napoleon III. Editor: So, the sculptures themselves would have reinforced that message. Curator: Exactly. The allegorical figures representing marine power, agriculture, and commerce symbolize France's global aspirations. Baldus’ photograph, though seemingly neutral, played a part in circulating these powerful images. By documenting these sculptures even in their nascent plaster form, he contributed to their eventual impact. It begs the question, how does photography change the aura of art meant for grand spaces when reproduced for wider distribution? Editor: That's fascinating. It shows how photography not only captures art, but actively participates in shaping its meaning and impact. Curator: Precisely. It’s a record of artistic process, but also evidence of the era’s understanding of how art functions in society and how photography shapes public perceptions. It invites us to reconsider what the purpose of these symbols really mean. Editor: I see that more clearly now. Thanks, that gave me a lot to consider. Curator: My pleasure. I have some thoughts to turn over as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.