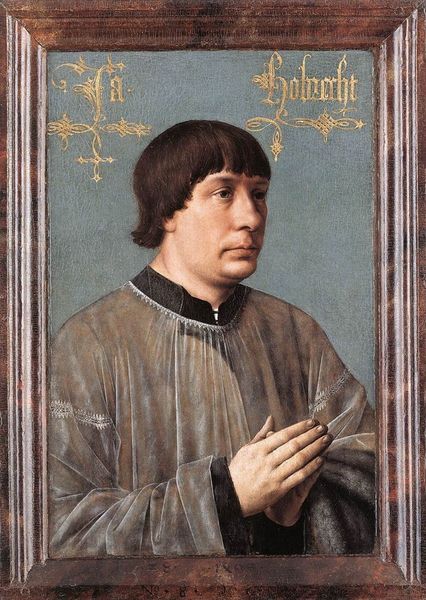

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

early-renaissance

#

realism

Dimensions: Oval, overall 12 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (31.8 x 26.7 cm); painted surface 12 1/2 x 10 1/4 in. (31.8 x 26 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today, we're looking at "Portrait of a Man," an oil on panel painting attributed to Hugo van der Goes, dating from about 1470 to 1480. It currently resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: He strikes me immediately as contemplative, almost mournful. The stark realism of his features against the muted background creates an intense focus on his interior world. And those hands clasped in prayer–a familiar symbol. Curator: Yes, the hands immediately suggest piety. However, the portrait transcends mere religious symbolism, particularly when considering the social hierarchies of the time. Portraits during the Early Renaissance were often commissions that signified status and power. It is a history painting in that it captures a particular moment in this individual's story, set against a delicate landscape, marking a place of privilege. Editor: And yet, his gaze seems almost vulnerable, defying that sense of power. The landscape itself, visible through the window, feels distant, almost ethereal. It reminds me of van Eyck in how naturalistic it appears despite that subtle distance. Is he gazing upon something longed for, perhaps? I think of similar iconographic usages within medieval tapestries when considering that far-off verdant scenery, it gives insight into his deeper longing for a terrestrial paradise. Curator: It’s fascinating to view it that way. Given that van der Goes himself experienced periods of intense mental and spiritual crisis, this portrait begs consideration within his own emotional landscape. Does this piece represent an understanding of internal struggle mirrored by external elements? Editor: I believe so. The landscape does suggest inner conflict as a motif. What do you make of the stark, unwavering focus on his realism? Are there cultural clues in the specific ways in which this individual has been presented? Curator: His realism, verging on hyper-realism, is not merely about objective representation; it makes an intersectional point that moves past mere aesthetics. Consider, during this period, idealized beauty standards reigned, particularly in the context of aristocratic portraiture, even as this man does conform with black and brown Renaissance dress codes. Van der Goes is pointing to a different facet of experience, potentially signaling dissent or even a claim to authentic, lived experience beyond superficial markers. Editor: That offers such a relevant social commentary when considered with the traditional presentation and iconography, it's clear his likeness is meant to convey his inner thoughts rather than the historical period. A subversion, if you will. Curator: Precisely! Van der Goes masterfully interweaves individual psychology with cultural discourse, offering a complex, thought-provoking meditation. Editor: Yes, examining how even the subtlest details – from the clasped hands to the distant landscape – act as potent reminders of cultural memory provides such profound insight into not only the subject, but to the artist himself. Curator: Well said. It underscores art's ability to serve as both a historical record and a vehicle for individual and collective narratives that continuously provoke critical thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.