Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

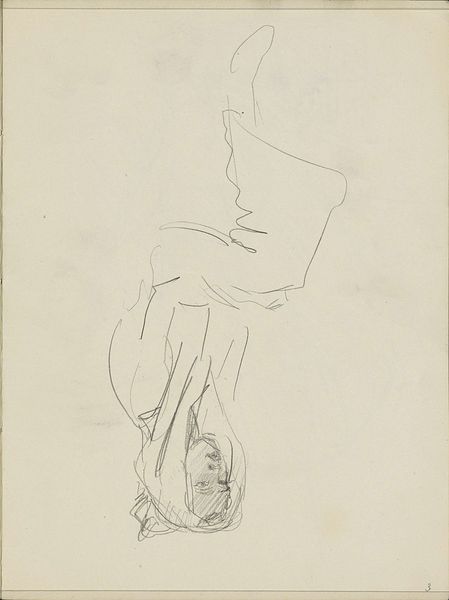

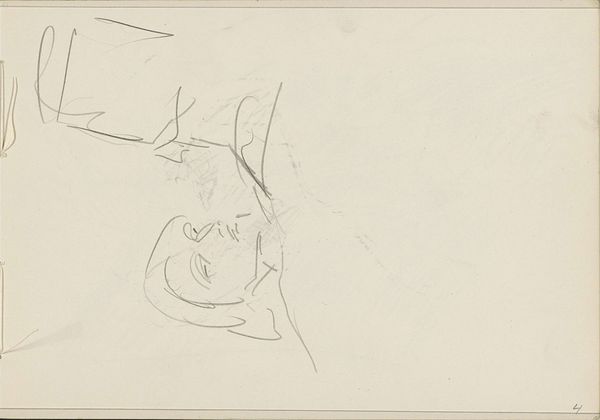

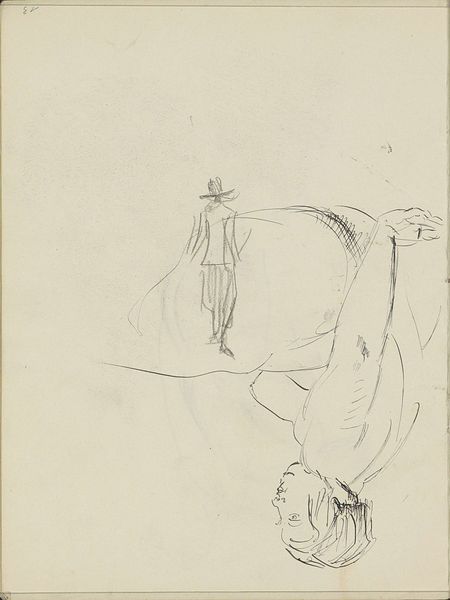

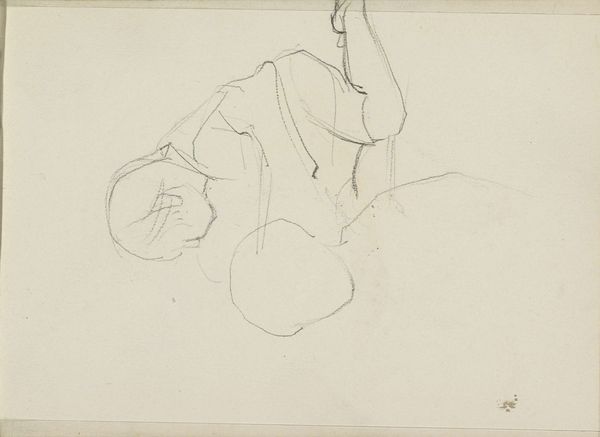

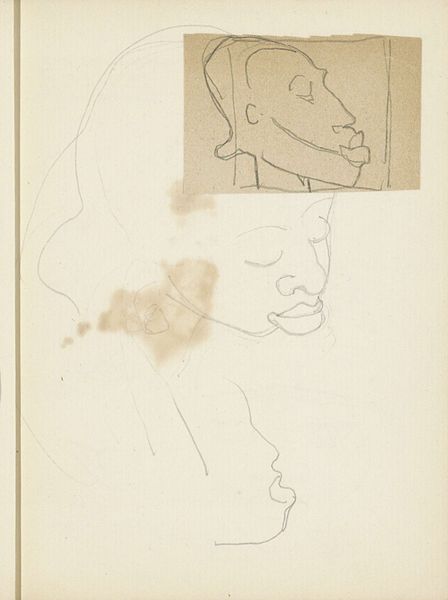

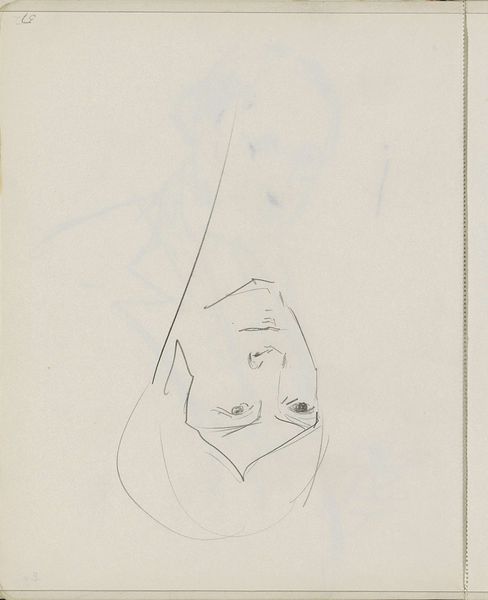

Curator: Here we have Isaac Israels' "Reclining Female Nude," a pencil drawing dating from around 1875 to 1934. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought? Intimacy. The simple lines almost whisper. The incompleteness makes it feel very personal, like a stolen glance. Curator: Exactly. Israels had a fascinating public life, but he also captured very personal and intimate moments in his drawings. How the museum collects and shows this says a lot about shifting definitions of what’s historically “important.” Editor: And this piece does subvert a lot of the traditional power dynamics we often see in nude art. The rough strokes and the nudity of the subject have been used by certain critics to assert power over her for generations, objectifying women under the veneer of artistic license, something that impacts real world biases today. But I think Israels challenges those norms here by only offering an incomplete sketch, by emphasizing her face instead of more overt symbols of sensuality and seduction. Curator: It's more vulnerable, wouldn't you say? Editor: Vulnerability is such a complex topic, it can depend on context. Curator: Of course, yes. But beyond its sensitive portrayal, consider the artistic circles Israels moved in. How Impressionism shaped the perception and acceptability of these fleeting, less idealized studies of the human body. Editor: The impressionistic style further democratizes the figure by allowing it to exist in an unvarnished state. It reminds us how movements like these provided fertile ground for conversations on race, class, gender, and other subjects that were usually avoided in polite society. Curator: It absolutely pushed those conversations into public view, although how "democratic" these spaces were in reality remains a complex issue, when we consider access and the dominance of male narratives. Editor: True. What Israels has shown us is what can result when creators take into account the world that his creation inhabits, how people’s perceptions can shift or remain unphased, depending on the context, but how no work of art can ever be isolated from those broader historical dialogues. Curator: Indeed. It prompts us to reconsider how institutions present even the simplest sketch in the grand narrative of art history. It’s really been illuminating exploring all of this in context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.