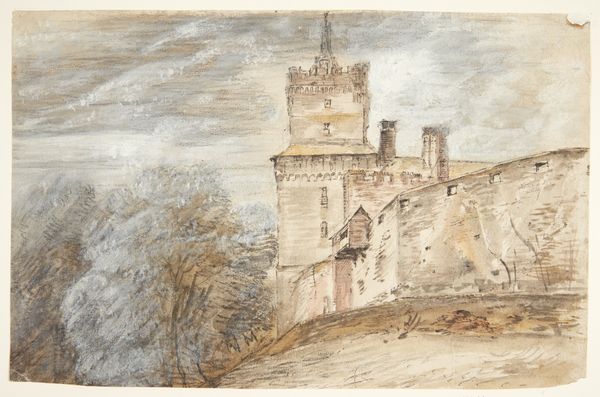

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet: 22.8 × 32.7 cm (9 × 12 7/8 in.) mount: 28.4 × 38.4 cm (11 3/16 × 15 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Here we have Peter De Wint’s "Lincoln Cathedral from the Castle Moat," a watercolor drawing from the mid-19th century. What strikes you first? Editor: An incredible sense of distance and the weight of history pressing down. The palette feels subdued, almost sepia-toned. It gives me a feeling of temporal displacement, as if viewing something from centuries ago. Curator: Indeed, observe the layering of forms: the dense foliage in the foreground leads the eye gradually to the imposing cathedral, which dominates the skyline. The artist's command of perspective here generates visual interest, emphasizing the monumentality of the architecture. Editor: It makes me think about power. Cathedrals like Lincoln weren't just religious spaces; they were visual declarations of authority and control within the social and political landscape of Victorian England. Did De Wint consciously portray this, or was it merely an aesthetic exercise? Curator: One could argue that, technically speaking, De Wint manipulates color temperature to create a certain optical hierarchy, with the warm hues of the cathedral drawing the eye, a compositional focal point further set apart through the subtle suggestion of atmospheric perspective, almost as a pictorial statement of architectural form, itself. Editor: The framing feels important too; using the natural, overgrown landscape in the foreground suggests an organic power pushing against the structures imposed on the landscape. What are the historical events, debates surrounding the church’s presence, the community's reaction to this grand building looming over their lives? The art prompts these queries. Curator: Setting aside those larger themes for a moment, look again at the use of line and wash in this landscape and the manner in which De Wint suggests both material and texture through transparent watercolor layering. Its structural success alone provides immense viewing pleasure. Editor: Of course. But consider the function of landscape art more broadly in this era; wasn't it about reinforcing ideologies, about naturalizing social hierarchies? These subtle visual strategies served larger, sometimes problematic narratives. It’s more than just looking, it’s a critical reflection. Curator: Point taken. Though appreciating it's visual cadence, in addition to any subtextual meanings, allows for a greater understanding. Editor: Agreed, the dialogue between form and context—always essential.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.