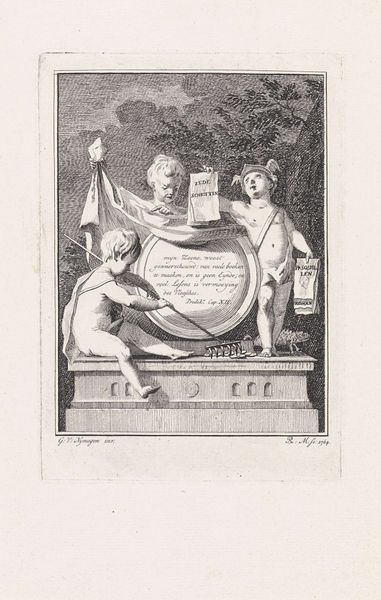

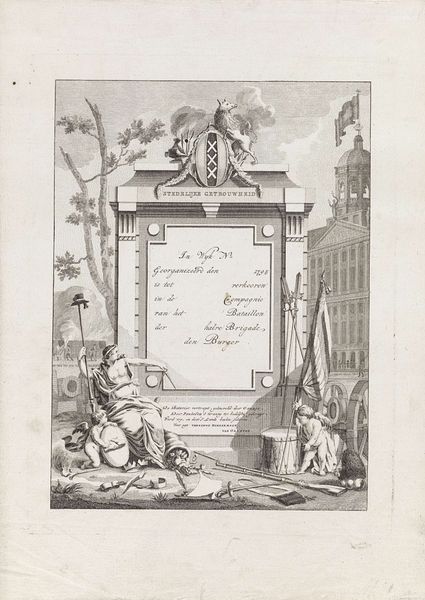

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 95 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Stembriefje voor een burger te Rotterdam, 1796," a print from 1796 by Hendrik Roosing. The neoclassical figures flanking the central cartouche give it a very formal, almost propagandistic feel, despite its small scale. How do you interpret this work, especially given the context of its creation? Curator: It's crucial to recognize the moment this print emerges from: the Batavian Revolution, inspired by the French Revolution. We see allegory and classical forms used to visualize these newly conceptualized “rights of man and citizen,” the emphasis on “fraternity” in the Dutch translation, which are meant to signal progress, civic virtue, and revolutionary change. Note the symbols that would resonate with people, for instance the fasces as an emblem for the people's power and civic unity, the emphasis on liberty, equality, and fraternity around the oval, the Roman garb, the "Rotterdam" signature for the "citizen's" place, as well as the shield showing 4 lions to emphasize strength. Do you see anything else related to that in terms of, perhaps, how gender and race factor into the visuals? Editor: I do notice the figures representing these ideals are feminized – suggesting a vision where perhaps the feminine embodies the Enlightenment principles? But also, the putti are white – whose 'rights' were being visualized and for whom? Curator: Exactly. By focusing on visual language and political context, we can dissect not just the aspirations of the revolution but also the limitations and exclusions embedded within its representations. Who *isn't* pictured is just as important as who is. It calls for a deconstruction, and prompts us to critically examine its message. Editor: That makes so much sense. Thanks for illuminating the power dynamics embedded in this seemingly simple print! I’ll definitely look at other historical artworks with a more critical eye.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.