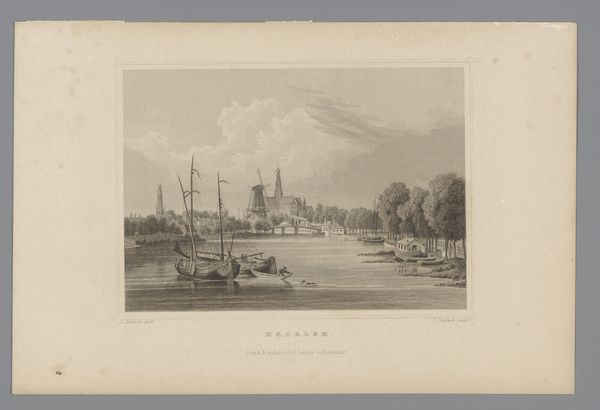

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 174 mm, width 246 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, this artwork has such a calm presence. It reminds me of a peaceful summer afternoon, lazy boats, dappled light... almost melancholic, isn't it? Editor: Yes, and what you are perceiving is precisely what the artist intended to capture. Here we have Carel Frederik Bendorp's, or rather Bendorp (I), rendering, in print form, of the "Stadsgezicht met het Spaarne en Waag in Haarlem," which translates to, a cityscape of Haarlem, focusing on the Spaarne river and the Weigh House. The image, crafted between 1786 and 1792, uses etching as a method on paper, adhering closely to a neoclassicist style. Curator: Neoclassical! Of course, the attention to clarity and order—the perspective feels meticulously planned, and despite all of these fine lines and detail—the overall affect somehow is soothing, a quiet snapshot from history... Do you think it’s romanticizing that period of Dutch history? Editor: Well, these depictions often serve a dual function. Beyond aesthetic appreciation, such artworks act as vital socio-historical documents. What stories could the position of women tell us in these harbor activities? Were new mercantile practices impacting class dynamics and social order? The questions these artworks elicit invite us to explore a comprehensive grasp of the intricate networks influencing 18th century Holland. Curator: I see the cityscape teeming with untold narratives. Just now, I am observing someone fishing, I am thinking… where does that activity place them on the socioeconomic scale? I am pondering their story... but I wonder if the print-making medium itself limits any subversive intent... Were these widely available and did this allow regular people to acquire them, influencing or impacting the circulation of revolutionary ideas? Editor: Precisely, we need to analyze print medium of that moment. Looking at how it circulated could provide crucial insight regarding any resistance movements through an artistic lens, because etchings at the time became more accessible and portable than painted canvases. That scale in the distribution meant radical views may reach an expansive viewership, challenging dominant sociopolitical narratives. Curator: Thinking about it, I would say, the weight house symbolizes trade, right? Editor: Yes, that is correct; it certainly anchored the city's commercial activities and therefore, societal norms. Curator: It leaves you wondering about the narratives that this quiet scene masks. Editor: Indeed, this tranquil scene encourages profound questions about society, progress and resistance from a seemingly uncomplicated window of that particular time and space.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.