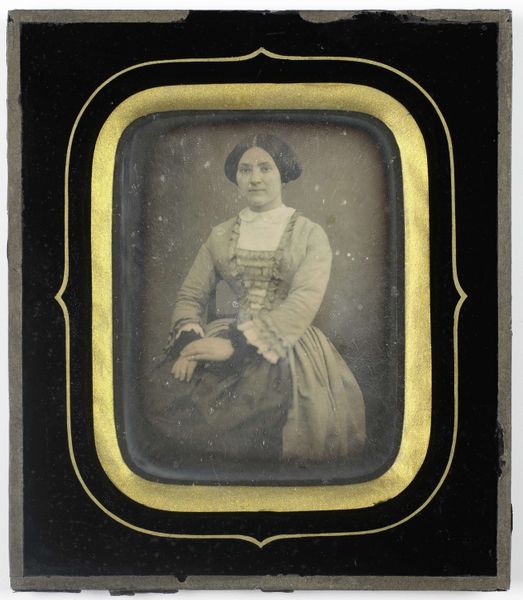

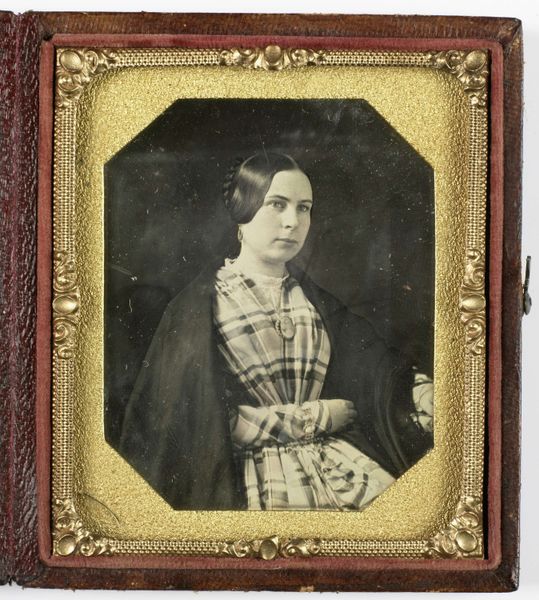

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

sculpture

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

Dimensions: height 72 mm, width 59 mm, height 130 mm, width 110 mm, thickness 4 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an intriguing portrait, simply titled "Portret van een onbekende vrouw," placing its creation somewhere between 1840 and 1860. What strikes you first about it? Editor: The reflective surface of the image grabs my attention. It's not a print; it’s almost jewel-like, hinting at the material process of its making. There's a directness I find compelling; almost as if it's pulled straight from an old mirror. Curator: Precisely! This is a daguerreotype, one of the earliest forms of photography. These images, rendered on silver-plated copper, held a unique cultural status. They were presented almost as luxury objects. Note how this example is housed within an ornate gilded frame, mimicking miniature portraiture of the time. It elevates photography into the realm of high art and remembrance. Editor: Interesting; there is labor and care in making it! But the anonymous subject complicates things, doesn't it? We lose so much of the narrative without her name, without her history written, its meaning rests primarily in the materials themselves, and what they signify socially. Curator: To some degree, yes, anonymity poses interpretive challenges, but this in itself provides access into a particular Victorian societal trope. Photography was becoming more accessible, but still signified elevated social status; portraits such as this one played an important part in constructing and reinforcing social identities. Who commissioned this daguerreotype, and why? And how would it have circulated? Editor: That last part feels pertinent; what were the conditions of photography and this specific photographic practice for this woman in her social-economic context. The lack of known provenance and the subject's relative anonymity pushes us to contemplate the relationship between photographic materiality, subjecthood, and circulation, wouldn't you say? Curator: Absolutely. The way photography blurred lines between art, commerce, and social practice renders it an incredibly important field of historical investigation. Editor: Well, examining it this way brings new meaning to this simple portrait, highlighting the intertwined dynamics of materials, history and personhood within art. Curator: Indeed; by studying art's function within its specific social contexts, we can decode powerful cultural and historical realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.