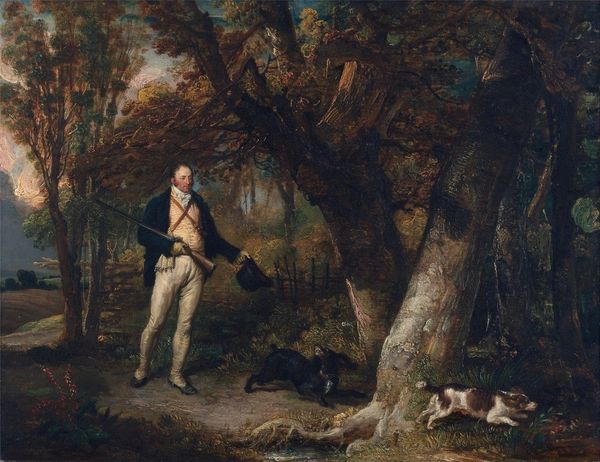

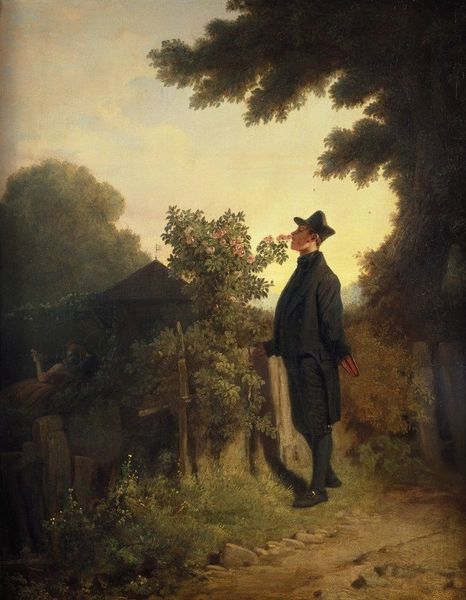

Dimensions: 148.6 x 207.6 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Before us is Joseph Wright of Derby’s oil painting, "Brooke Boothby," completed in 1781. It’s now held here at the Tate Modern. Editor: Right away, I’m struck by how intensely *chill* this guy is. Total languid elegance. Look at him sprawled out, mid-think, bathed in that sunset glow. I bet his dating profile would say something about "intellectual musings." Curator: It's a defining work of Romanticism. It presents Boothby, a known intellectual and writer, in an idealized state of melancholy, reflecting the period’s preoccupation with sentiment and the natural world. Consider the Enlightenment interest in science with the burgeoning aesthetic interest in emotions and drama. Editor: Melancholy, yes! There’s almost a Byronic vibe – all dark thoughts and brooding. The composition draws your eye right to his face, but then you notice the book under his hand, grounding him in reality even as the light sends him into some imagined place. But did anyone *really* recline like that for real? Looks wildly uncomfortable. Curator: That pose is quite intentional. It reflects the fashion for portraying individuals within carefully constructed pastoral settings. Wright consciously positioned Boothby against the backdrop of the natural world to signal his sensibilities. The book too speaks to the values of refined sensitivity and erudition among the landed gentry. Editor: It feels like we’re intruding on a very private moment. The darkening trees around him press in, and yet, he’s illuminated—gorgeous and a little ridiculous. It's like stumbling onto a theatrical performance staged just for the sunset. He practically *demands* to be painted. Curator: And, in a way, the painting fulfills the societal role of art during the late 18th century, emphasizing an individual's character and societal position but through a more personal, emotional lens. Editor: All in all, you leave with the sense that the artist *liked* the subject, no? It goes deeper than any stuffy commission – there’s fondness radiating from the brushstrokes. Curator: Indeed, Wright succeeds in painting more than just a portrait, instead conveying an aura that captured the aesthetic inclinations of an era, but also its emerging cult of personality. Editor: Absolutely, and isn't that what great portraits do? More than just record likeness, they somehow give us an inner landscape of another person’s mind, or even the echoes of an epoch itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.