photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 49 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

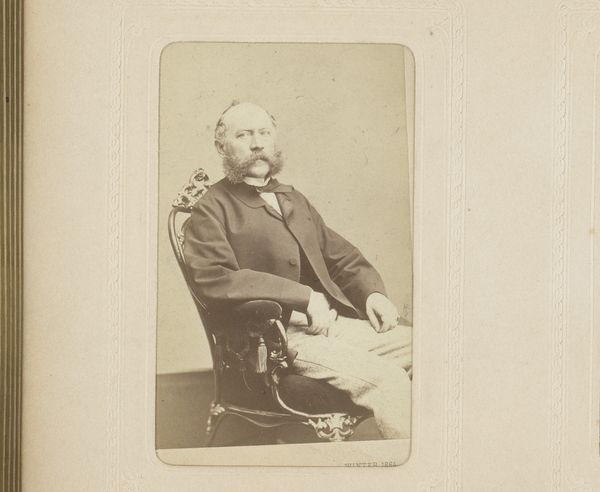

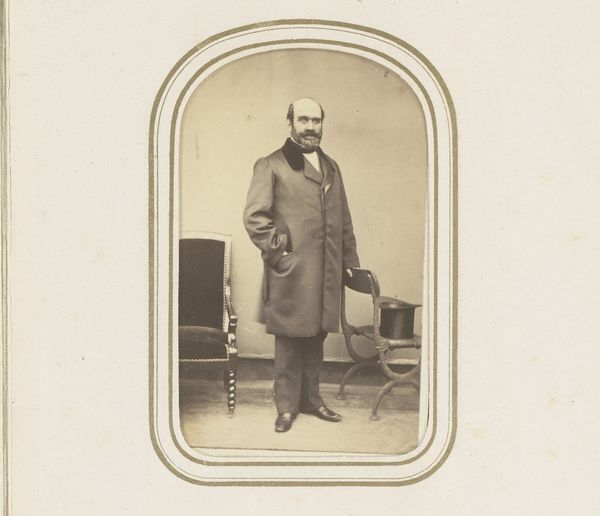

Curator: This captivating gelatin-silver print, created sometime between 1850 and 1900, presents us with a dignified "Portret van een zittende man met baard" or "Portrait of a seated man with beard", possibly by Ernst Wolffram. What are your first thoughts? Editor: It has such a somber feel. The formality of the man's attire, combined with the slightly blurred focus, almost gives the impression of a fading memory or a lost ancestor peering through time. Curator: Absolutely, that resonates with the historical context of photographic processes then. Gelatin-silver prints allowed for finer details and a wider tonal range compared to earlier photography, but required very precise labor to prepare, sensitize, expose, develop and fix the glass plates, so we also see a tension between technological advancement and intensive handwork. The commercial studio portrait would have also served a material function for personal use. Editor: Indeed, and if we place this photograph within a broader socio-political context, what kind of access to resources allowed this portrait to happen? Whose story gets told, and whose is deliberately or negligently overlooked due to marginalization? Curator: Exactly. Understanding the materials—the gelatin emulsion, the silver particles, the chemicals—and the labor involved allows us to consider the portrait studio as a site of early industrial capitalism and to unpack ideas about artistic labor and consumerism at the turn of the century. Editor: Let’s consider this man's clothing and its meaning during that era. Was the cut of his coat standard for a particular class or occupation? Those details could offer insights into his status and the performance of identity conveyed here. Curator: The details are remarkable when we begin to examine this image as a constructed commodity for middle-class identity formation. Editor: Seeing this portrait with a consciousness towards the social structures of the past deepens my perception. It prompts reflection on how societies create visible records—and whose visibility gets prioritized over others. Curator: It reminds us that photographic portraits of this era are artifacts embedded within complex economies of image production, and the act of making, viewing and now exhibiting this photo offers a chance to reflect on those historical processes. Editor: Agreed. What seems a straightforward image opens onto important questions about labor, visibility, and how the past informs our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.