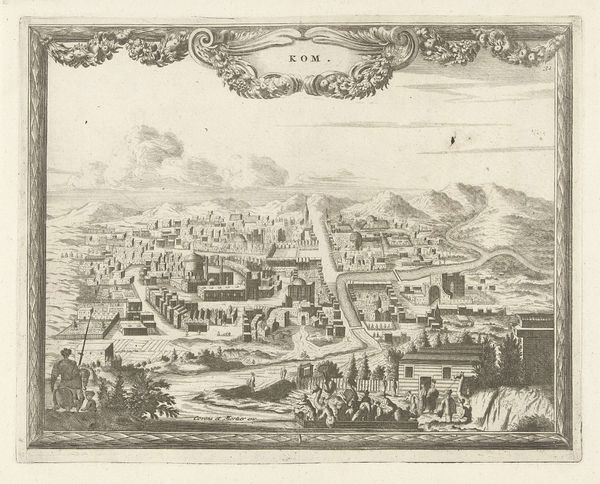

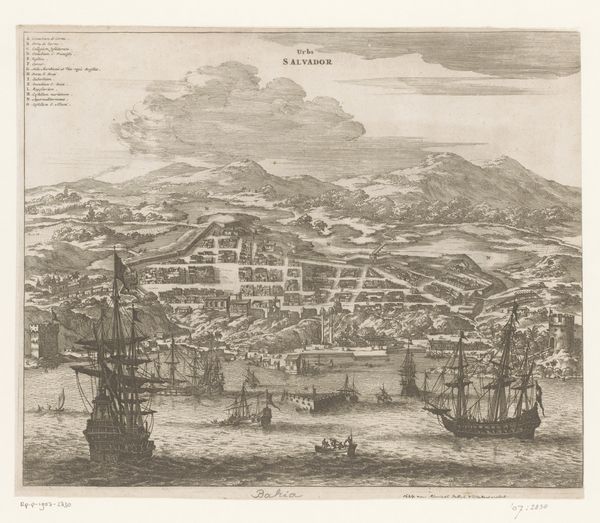

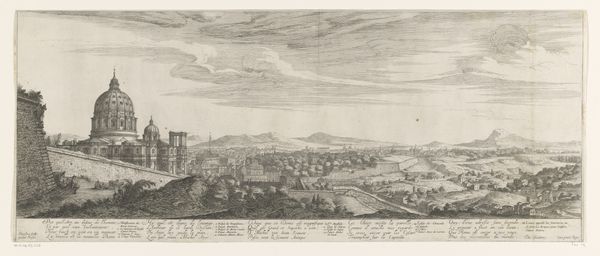

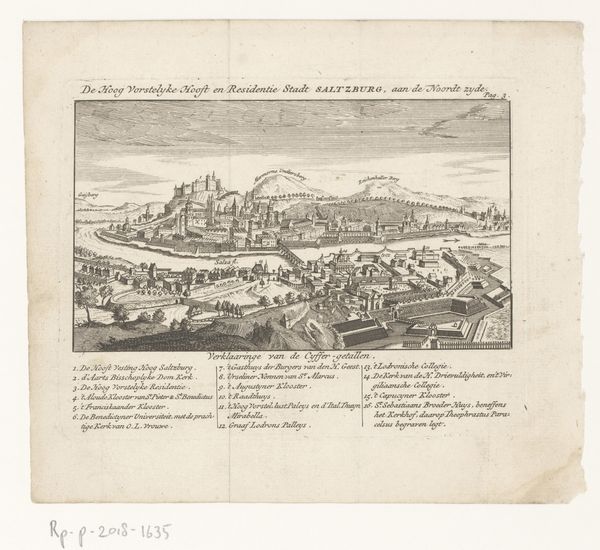

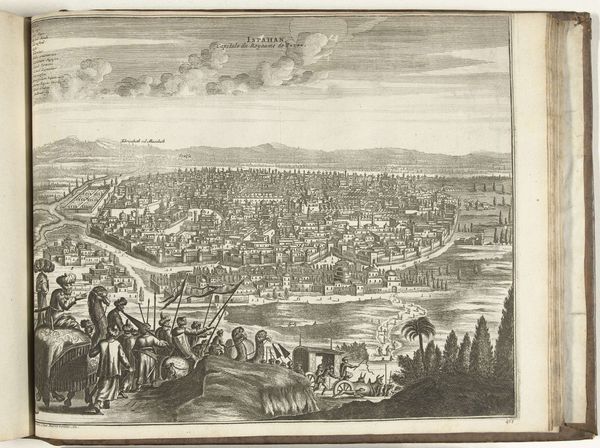

print, engraving

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 300 mm, width 390 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

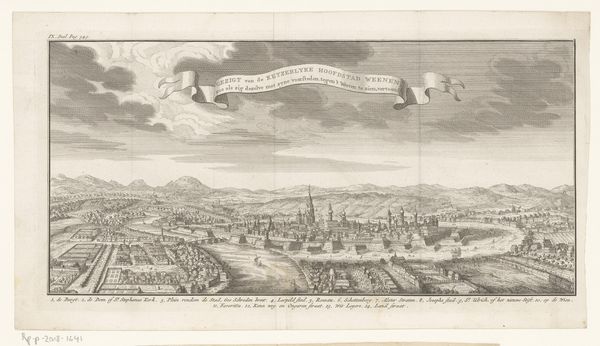

Curator: Here we have a look at the engraving titled "Gezicht op Astrakhan, 1726," which translates to "View of Astrakhan, 1726." It’s an anonymous piece residing here at the Rijksmuseum. What's your first reaction? Editor: It’s bleak, surprisingly desolate. The stark monochrome amplifies a feeling of almost suspended animation despite the bustling figures populating the foreground. Curator: The medium itself, engraving, lends itself to this crisp delineation of form. Note the strategic deployment of hatching and cross-hatching, employed to construct the volumetric space, casting shadow upon the city walls and implying atmospheric perspective as we gaze towards the distant, pale mountains. Editor: But doesn't that very starkness provide insight into 18th-century geopolitical vision? Astrakhan was, at the time, a critical point of contact and control, wasn't it, straddling Russia and Persia at the mouth of the Volga? This piece, I think, is designed to convey a sense of imposing stability for political intentions. Curator: An interesting socio-political consideration that layers on the effect. From my perspective, notice how the composition relies on a pronounced horizontal axis defined by the cityscape, then counterbalanced with these almost feverishly rendered details in the lower register near the river. Editor: Absolutely, it directs the viewer's gaze upwards to the architecture as the supposed representation of "order," with people in transit down below, perhaps deemed more transitional than their static backdrop. I notice as well how that small fluttering banner bearing the city's name presides over everything like a title card— a claim of ownership. Curator: Indeed, it performs on multiple semiotic levels. It signifies location, and implicitly, jurisdiction. That being said, perhaps its power lies paradoxically in its ability to distill grandeur and utility through a relatively constrained range of markings. It feels immediate despite its subject, almost reportage rather than romantic vista. Editor: I see that point. It becomes an almost ethnographic document as much as it's aesthetic posturing. I suppose analyzing it has provided us both perspectives: of a visual object as a tool in state-building, and as a standalone aesthetic document operating according to structural principles. Curator: Yes, precisely, offering a multi-faceted view as valuable and lasting as this carefully wrought rendering of a moment nearly three centuries past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.