print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

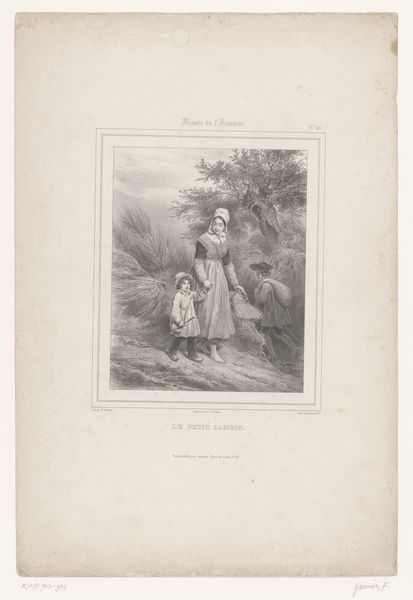

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 305 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

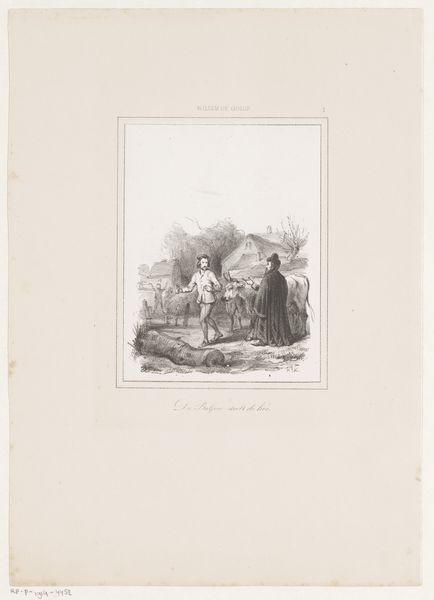

Curator: This print, created in 1829 by Jean-Louis Van Hemelryck, is entitled "Koning Willem I helpt een vrouw" – "King William I helps a woman." It’s rendered in an old engraving style, showcasing a scene steeped in narrative. Editor: Oh, it's like stumbling upon a quaint play. Everything feels poised and staged, from the carefully placed trees to their studied expressions. There's almost a theatrical air to it. Curator: Precisely. Genre and history painting converge here, framed by the romanticism characteristic of the era. Note the figure of the king—positioned not in regal splendor but engaged in humble assistance. He helps a woman laden with a large sack, while a donkey waits patiently nearby. The print attempts to portray him as accessible, involved with the daily lives of his people. Editor: So, the picture becomes less about William I as monarch, and more about... William I as one of us, schlepping along like everyone else, sort of. Curator: It's a strategic narrative. This representation serves as a visual articulation of power seeking legitimacy. In 1829, during the reign of Willem I, national identity and royal authority were consistently negotiated through public art. Editor: I see it as the same desire of politicians to look, I don’t know, authentic. “Here I am! Pushing this boulder WITH you, citizen!” It feels manufactured. I mean, who carries goods dressed in that elaborate coat and top hat? It clashes horribly with the gritty, laboring woman! Curator: It's a clear contrast, highlighting social class, and yes, perhaps underlining the artificiality of this manufactured empathy. The lines of the engraving are meticulously etched, almost too perfect. Editor: I see, in a cynical kind of way. Is it weird that I'm more drawn to the donkey than the King? I see genuine suffering in its stance… poor, poor, creature. It speaks of resilience—of being ever-burdened but remaining patient. Curator: That resonates! Elevating a historically subjugated perspective brings renewed layers of reading. Editor: Maybe we all should remember to pause and look at art beyond its stated intent! Curator: Agreed. Seeing is, inevitably, interpreting!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.