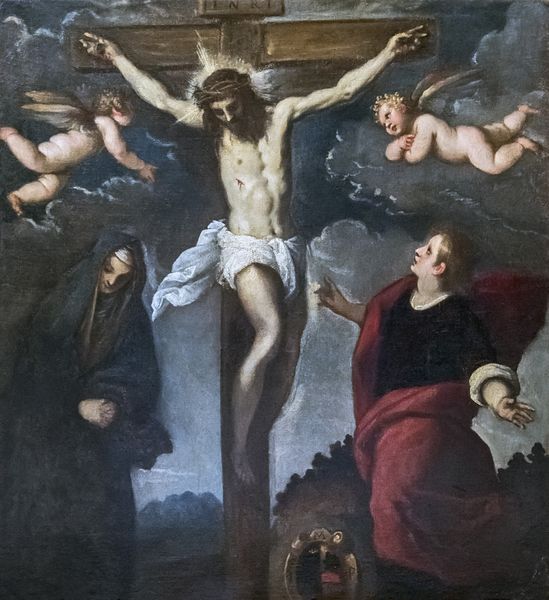

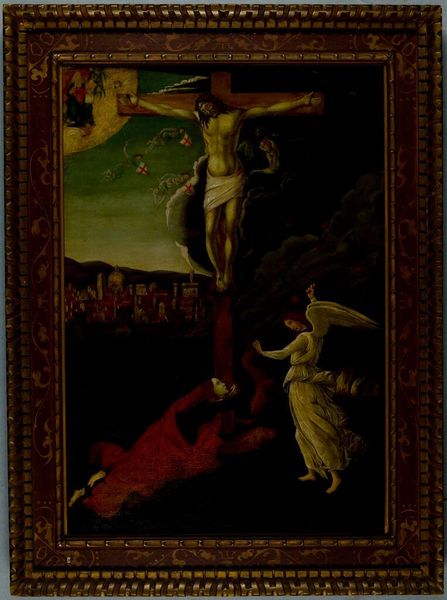

Crucified Christ Triumphant over Death 1621

0:00

0:00

painting, oil-paint

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 16 1/8 × 9 1/4 in. (41 × 23.5 cm) (sight)16 1/8 × 9 7/16 in. (41 × 24 cm)21 1/8 × 14 5/8 × 3 1/8 in. (53.7 × 37.1 × 7.9 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Oh, wow, what a stark contrast. The stark white figure against the deep, almost consuming darkness. It gives it such an…unsettling beauty. Editor: We are looking at "Crucified Christ Triumphant over Death" crafted in 1621 by Paolo Guidotti, also known as Cavalier Borghese. It's an oil painting currently housed at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, a powerful example of Baroque allegory. Curator: Allegory is right! I see this drama unfolding, bathed in a really unsettling light. The mourners at the base feel so raw. The color choices make me almost cold. Is that the allegory of Death being trampled beneath Christ? I think there are a lot of clever devices employed in this canvas. Editor: Exactly. Observe how Guidotti situates Christ, almost floating, above figures symbolizing despair and death. The crushed figures beneath Christ represent vanquished Death. The entire composition, its Baroque dynamism and dramatic light, emphasizes triumph, specifically that of spiritual salvation overcoming earthly mortality. There are interesting ways that art can be deployed for specific effects here in service of Christian values. Curator: Spiritual salvation, sure, but visually it’s the struggle that speaks loudest to me. Look at those faces. They reflect deep suffering. And even in triumph, there’s this fragility in the figure of Christ himself. It’s like victory and defeat coexisting on the same plane. Or even just in the same being. That is complex work in this painting. Editor: The intentional complexity underlines core socio-religious narratives of the time. Remember, the Baroque period used art to reinforce faith and power. Paintings like this were meant to emotionally move viewers, driving home specific religious messages in very manipulative ways! Curator: Manipulative indeed! Even centuries later, those high-contrast emotions are hard to shake. This Baroque is saying more than the picture first let on, which, admittedly, has quite a bit going on to begin with. Editor: I agree. From a historical view and in our time, we continue grappling with representations of power, mortality, and the stories we choose to tell about them. So maybe, looking at it this way, this painting from 1621 holds some relevance.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Paolo Guidotti was a true Renaissance man. Interested in flying machines, he made wings from whale bones, feathers, and springs and attempted to fly off a roof, breaking his leg. To study anatomy, he reportedly removed body parts from recently buried corpses. He also practiced architecture and law. Commentators have called him “a crazy master” whose expressive, eccentric style verged on the “hallucinatory.” Guidotti’s eccentricity is on display in this haunting, unusual Crucifixion. He set the tragic scene in the darkness of night, with Christ’s tortured body stilled by suffering and his head bowed in sorrow. Below the cross is a heap of vanquished figures: Death, represented as a skeleton; Evil, represented as the Devil or Lucifer; and Sin or Flesh, symbolized by the bound, naked figures of Adam and Eve. The six mourning women represent the six Maries—devout figures in the bible with Mary in their name—among them the Virgin Mary, in the blue mantle at left, and Mary Magdalene, kneeling at Christ’s feet. The other four might be Mary of Clophas; Mary, mother of James and John; Mary of Bethany, sister of Lazarus and Martha; Mary, mother of John Mark; and Mary of Rome. This small devotional painting was likely made for Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, the future Pope Urban VIII (1623–44). Dated 1621 by the artist on the verso, it was executed just two years before Urban’s election to the papacy. The work can be traced in inventories of Rome’s famous Barberini collection throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.