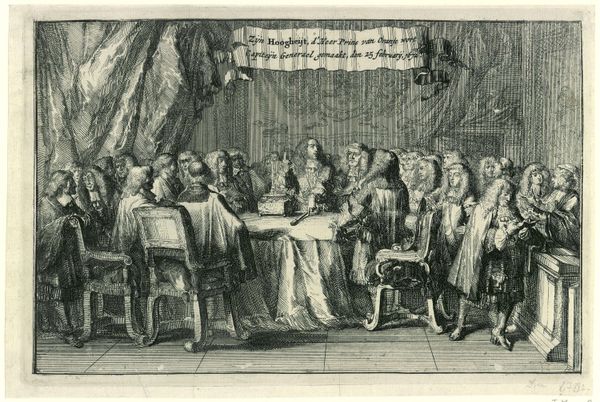

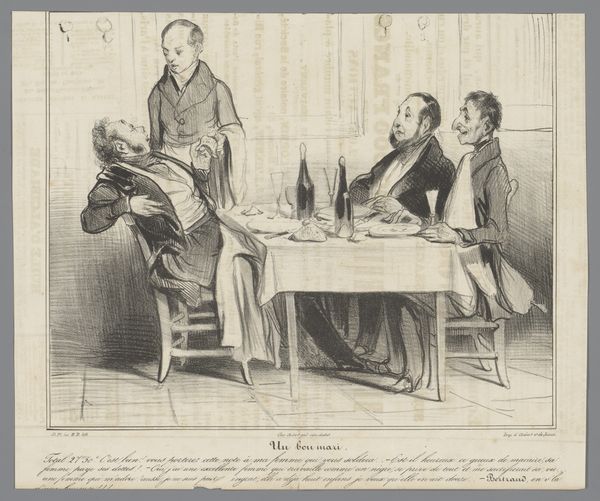

lithograph, print

#

lithograph

# print

#

caricature

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

modernism

Dimensions: overall: 36.2 x 49.1 cm (14 1/4 x 19 5/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

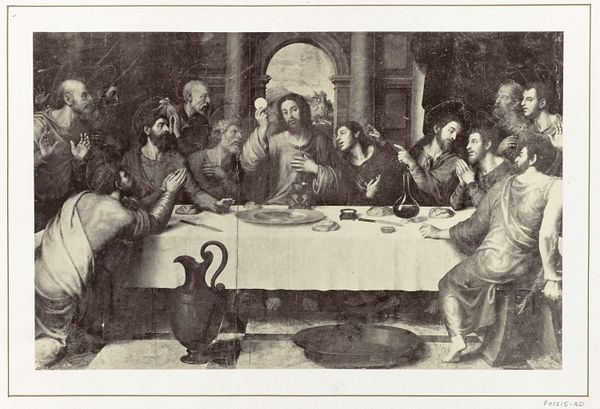

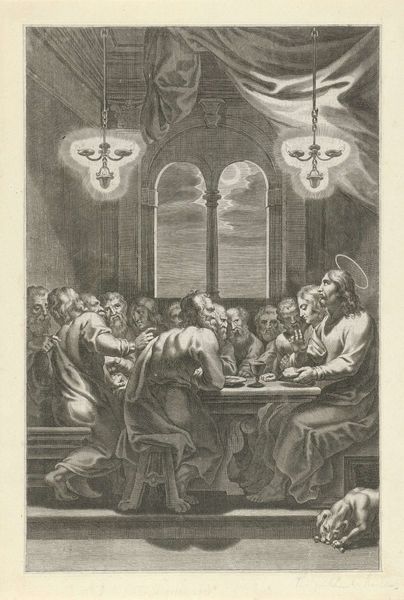

Curator: Looking at "Scène révolutionnaire: Parody on the Last Supper," a lithograph print made in 1834 by Auguste Bouquet, I am struck by the satirical humor employed within such a monumental art-historical reference. Editor: My first impression is how biting this caricature feels. It has an almost uncomfortable level of sharpness—the etching lines feel acidic. It's all so stark, focusing our attention on the people around that table. What is happening here? Curator: Well, we can see Bouquet’s clever manipulation of Da Vinci's "Last Supper." Instead of Christ and his disciples, we have leading political figures gathered, though portrayed here with clear disdain. It's a commentary on the post-revolutionary political landscape in France. Editor: Notice the choice of lithography; the way it can be mass-produced made this piece widely available and affordable, and it enabled critical social commentary to circulate broadly, which really speaks to the political climate and accessibility. It puts the means of criticism directly in the hands of the people. Curator: Precisely. The use of caricature was a potent weapon against authority. Artists could mock figures of power and expose their perceived hypocrisy to a large audience. These prints would appear in journals, passed around in salons, reinforcing shared opposition. Note also how genre painting conventions further satirizes and democratizes the political critique; Bouquet makes history painting and political life newly relatable by dressing it in genre codes. Editor: Look at the central figure, positioned where Christ would be, but instead, she's holding a prominent chef’s hat... Almost as if she is "serving" the nation. She literally embodies materiality by controlling the "table." Curator: I think the 'pears' that dominate the image cannot be overlooked as a political signifier, a coded insult directed at King Louis-Philippe whose pear-shaped head became the subject of endless lampoons. He quite literally sits among, and is 'served' by revolution! Editor: It's such a clever, biting commentary on power, crafted using the readily accessible material of lithography. Seeing the revolution from this perspective shifts how we approach the very materiality of printmaking. Curator: Absolutely. Bouquet provides us with an engaging lesson on how public image and artistic interpretation become crucial aspects in shaping socio-political history and identity. Editor: The subversive commentary available via accessible materials forces us to confront not just who holds power, but the tools by which that power is challenged and disseminated to the masses.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.