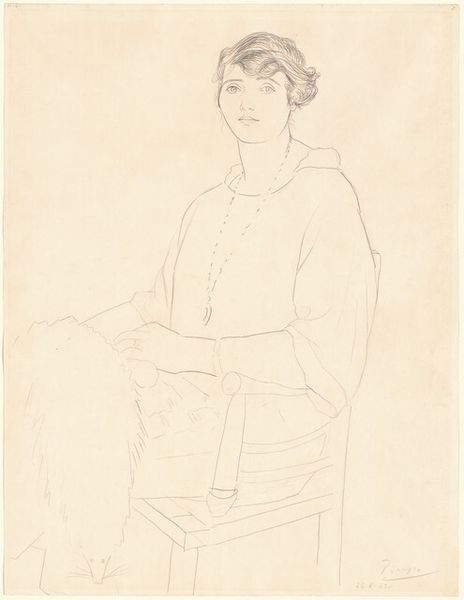

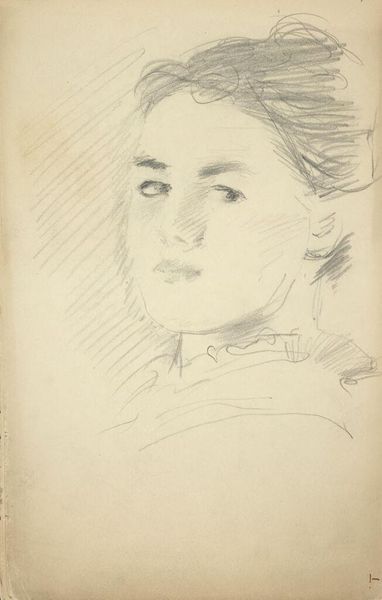

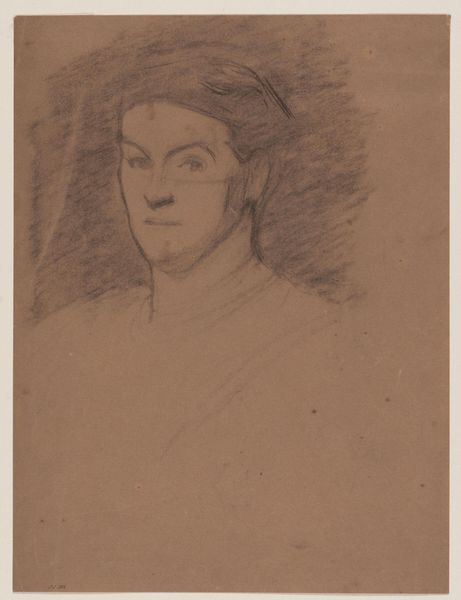

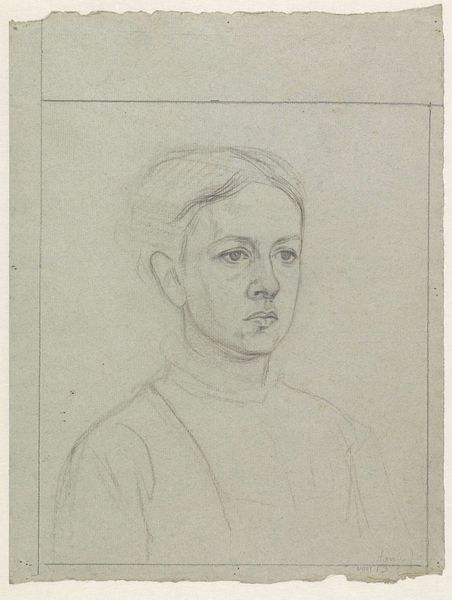

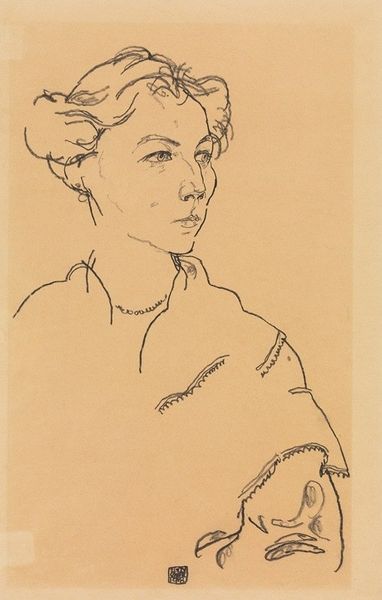

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

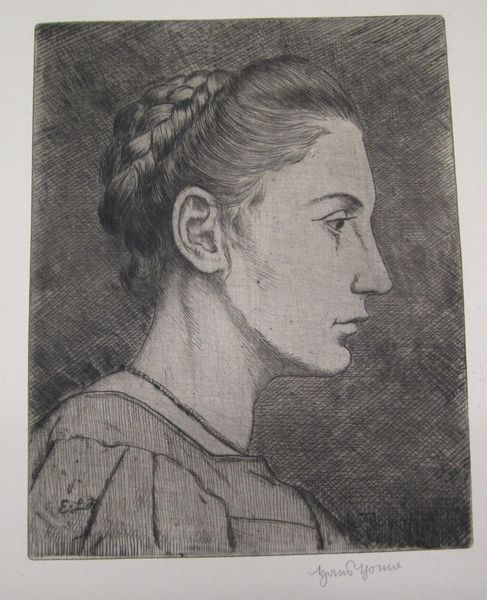

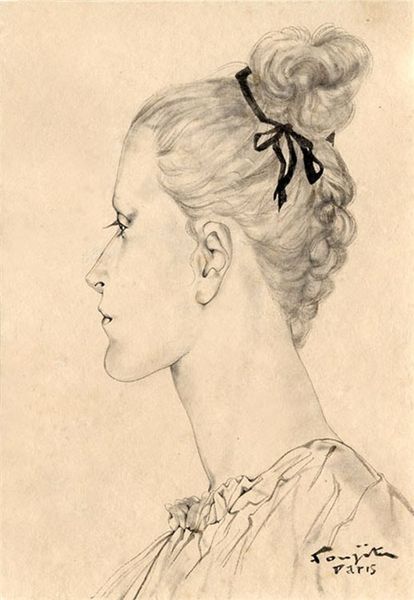

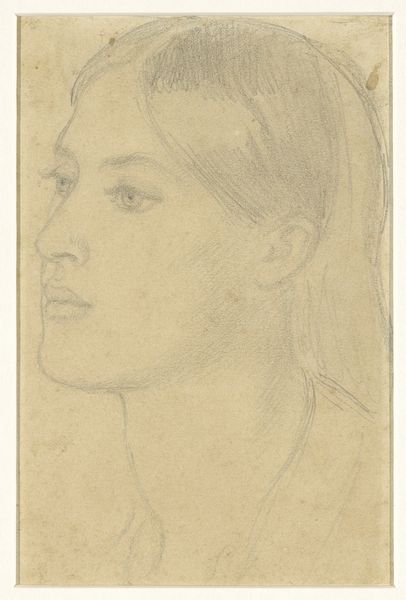

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

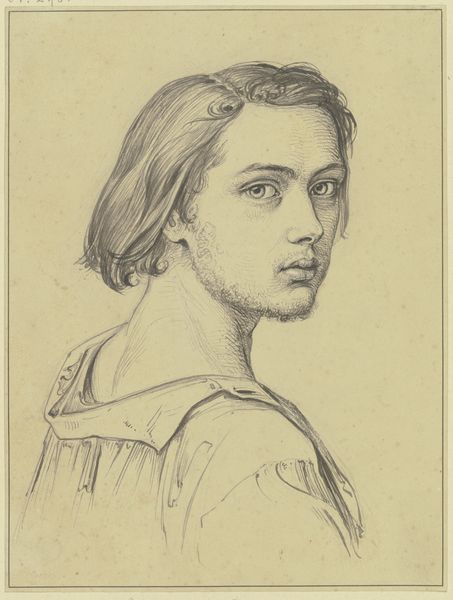

pencil

#

portrait drawing

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Editor: Here we have Richard Nicolaüs Roland Holst’s pencil drawing, “Portret van Kootje Martinet,” from 1905. It has such a delicate, almost ethereal quality to it. What strikes you about this piece? Curator: Well, looking at this portrait through a historical lens, I am immediately interested in the subject. Who was Kootje Martinet? Portraits are rarely just likenesses; they reflect the social standing, or the aspirations, of both the sitter and the artist. Do we know much about her? Editor: I believe she was part of the artist’s circle. A friend, perhaps? Curator: Precisely. Consider then, the context of early 20th century artistic circles. There's often a conscious rejection, or redefinition, of bourgeois norms. A simple pencil drawing, rather than an elaborate oil painting, might signify a deliberate move away from formal, establishment portraiture. It invites intimacy, doesn't it? We seem to see something sincere here. Editor: That's interesting. So the medium itself makes a statement about the relationship between artist and sitter, and their stance within society? Curator: Exactly. The choice of pencil, the almost unfinished quality, even the way the background is only suggested, contributes to a feeling of accessibility, a lack of pretension. It almost pulls the viewer into their world, questioning formal societal portraiture, and creating an artistic shift. It reflects and reinforces Roland Holst's artistic ethos, in relation with his peers. It all speaks volumes about the values of that specific artistic community at the time. Does this consideration change how you perceive the work? Editor: Absolutely. I hadn’t thought about the choice of medium as a social or political statement. Seeing it now enriches my understanding a lot. Curator: And that's the beauty of art history – uncovering those hidden dialogues and power dynamics embedded within the visual language.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.