tempera, painting

#

portrait

#

high-renaissance

#

tempera

#

painting

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: 65.3 x 46.4 x min. 2.7 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

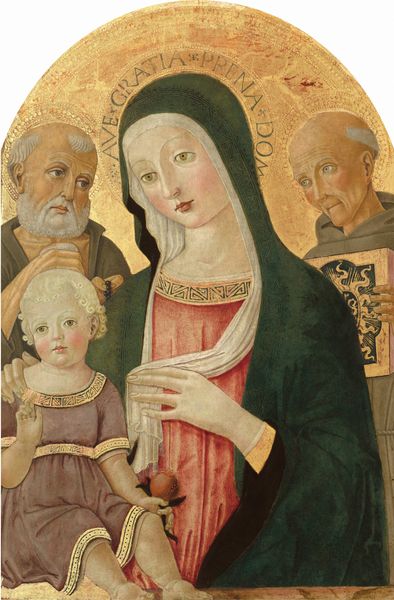

Curator: This tempera on panel, dating to about 1485, is "Virgin and Child with Saints Peter and Paul," by Neroccio de' Landi. You find it a somber, reflective image, wouldn't you say? Editor: Indeed. What strikes me is the evident handwork. Look closely, you can see the grain of the wood showing through the paint, almost asserting its presence in the divine scene. Curator: Right, and beyond just being materially present, consider Saint Peter with the keys, the direct linkage to the papacy and the earthly power structure. The very tool needed for access and divine approval is laid bare right there. Editor: That’s true. And note the choice of tempera, which lends itself to detailed, meticulous rendering, so different from the bravura of oil paint. There's a deliberateness here, an economy even. What was it like, culturally and economically, to have materials to render at this level of skill in Sienna in the late Quattrocento? Curator: I’d say it speaks to the wealth of symbolism typical of the time; the dove for instance in baby Jesus' grip and Peter with his Keys offer obvious visual reinforcement to established authority, each layer building trust and acceptance. Editor: Visual, yes, but how was the paint sourced, who prepared it? Think of the apprentices grinding pigments. The gold leaf in the halo must also carry some heft beyond just monetary or aesthetic, both metaphorically but also literally from the social labor needed for their production, do you think? Curator: Ah, yes. By employing gold leaf so carefully, a timeless appeal beyond cost to reach for, and root itself in, eternity; that sense of unshakeable religious order feels paramount, as seen by her stoic and calm presence amid two influential apostles. Editor: Ultimately it all adds up to a carefully manufactured devotion, using precious materials. From wood to finished iconography, each choice serves this sacred social structure as its true intent. Curator: Yes. And that the artist made the decision to ground the otherwordly presence through symbols into relatable truths is rather grounding. Editor: Very insightful to connect symbolism with labor; it seems all comes from someplace physical ultimately.

Comments

stadelmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

The historian and city librarian Johann Friedrich Böhmer (1795 – 1863) was a member of the Städel administration from 1822 to 1834. He bequeathed to the museum works by his contemporaries, for instance Ferdinand Olivier and Johann Anton Ramboux, as well as two early Italian paintings. Only a year later, the Städel received a further twenty-three Sienese paintings – including this panel – which Böhmer had initially given to the Verein für Geschichte und Alterthumskunde. As that society had no use for them, it exchanged them for a pair of old pistols.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.