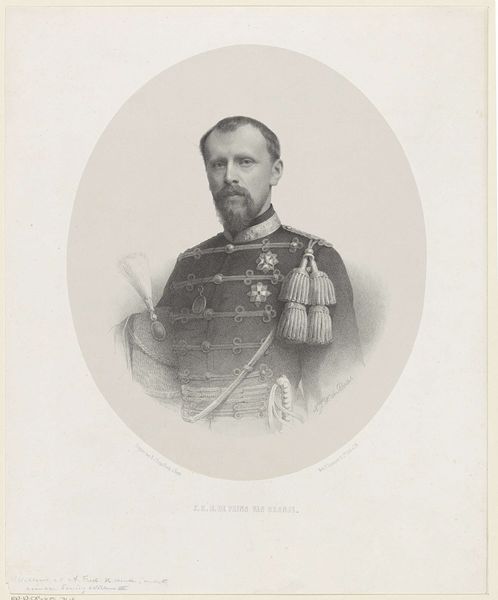

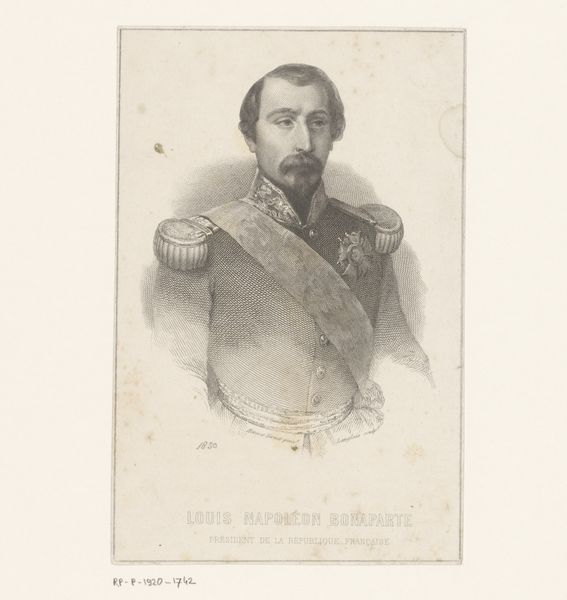

Portret van Willem III, koning der Nederlanden 1849 - 1853

0:00

0:00

hermanusjohannesvandenhout

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 365 mm, width 253 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is "Portrait of Willem III, King of the Netherlands," an engraving dating from 1849 to 1853 by Hermanus Johannes van den Hout, residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's striking. The almost photographic detail achieved through engraving really lends itself to a sense of formal authority, doesn’t it? The man practically radiates regal composure, even in a simple print. Curator: Indeed. What’s interesting to me is the materiality. This isn’t a grand oil painting intended for a palace, but a print. Consider its role: likely mass-produced for distribution, bringing the image of the monarch into homes and public spaces. It's about crafting and distributing an image of power. Editor: Precisely. The image of royalty, rendered accessible through the printmaking process. This allows for wider political and social impact beyond the elite circles who commissioned original portraits. The fact that the artist selected this technique informs our understanding of mid-19th century Dutch society, really, Curator: Absolutely. And look closely at the details, the textures meticulously rendered. The sharp lines of his uniform contrasted with the softer shading of his face – an impressive feat of craftsmanship, I think, regardless of who the sitter may be. There’s a clear engagement with the visual language of power here. How might its replication affect our view on the original and how its intention has survived throughout time? Editor: It presents a constructed persona. We see the king adorned in military attire. That emphasizes a specific kind of leadership. The symbolic weight of these embellishments contributes to how the image and office were perceived. This all feeds into the politics of imagery in an age rapidly changing with growing press availability, and shifting national identity. Curator: Considering its reproductive nature, and accessible qualities for different economic segments, its artistic qualities seem almost secondary to the portrait’s socio-political purpose. The very existence of this piece underlines the tension between art and propaganda. Editor: Very well said. It pushes me to examine the power dynamics at play—how readily reproducible images impacted conceptions of national leadership. A compelling reminder of the political dimensions embedded even in seemingly straightforward portraiture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.