photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

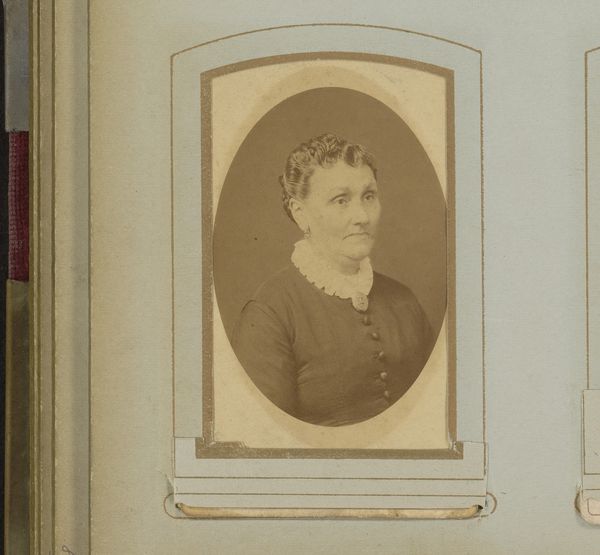

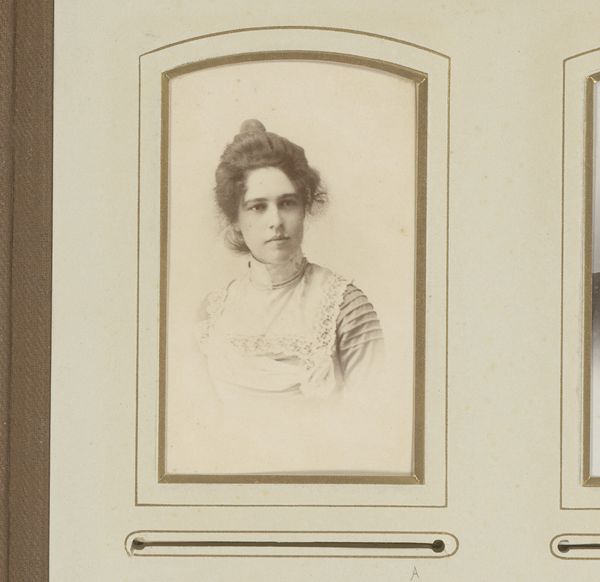

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

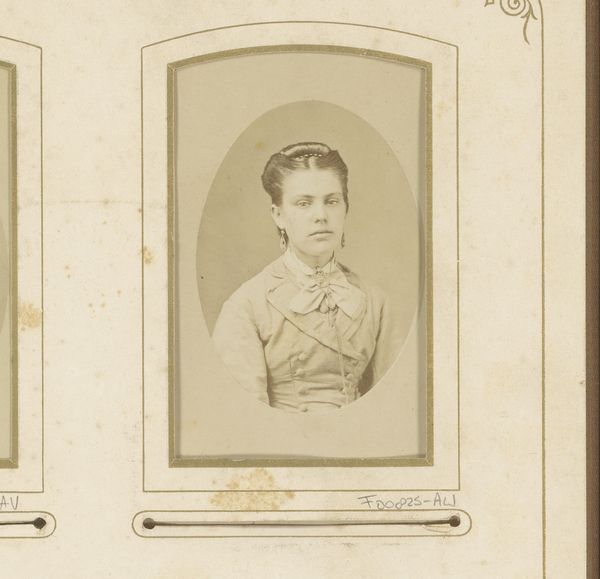

Editor: Here we have Jan George Mulder’s “Portret van een vrouw,” created sometime between 1865 and 1887. It’s a gelatin-silver print photograph, capturing a woman in formal attire. I’m immediately struck by the flatness and lack of depth. What can we understand from this early photographic technique? Curator: Consider the material realities shaping this image. Gelatin-silver prints, widely adopted then, relied on commercially produced materials. The availability and quality of gelatin, silver nitrate, and photographic paper would fundamentally affect the image’s tonal range and archival stability. Look at how the processing—the darkroom chemistry, the labour involved in coating and developing—dictates the final aesthetic. Does that affect how we consider this as an art object? Editor: I see what you mean. The process is crucial, but is it art or documentation then? Curator: That distinction collapses here. The subject’s clothing, the pose, the mounting—all constructed for the camera. Early photography democratized portraiture, yes, but also became a site of manufactured identity and aspiration for a rising middle class. How might her clothes and ornamentation speak to ideas of material consumption? Editor: Her jacket and bow look quite tailored; the jewelry isn’t ostentatious, but clearly present. So, the photograph becomes both record and aspiration? Curator: Precisely. The studio portrait’s affordability put this kind of carefully constructed image within reach, connecting art production to social mobility and shifting aesthetic values around how people wanted to be represented. This photograph is, ultimately, evidence of that new and ever-changing landscape of representation and consumption. Editor: I see it in a totally new light now, realizing that the processes and materials were as meaningful as the sitter! Curator: Indeed! And by acknowledging those material and economic forces, we uncover layers of social meaning often overlooked in traditional art historical narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.