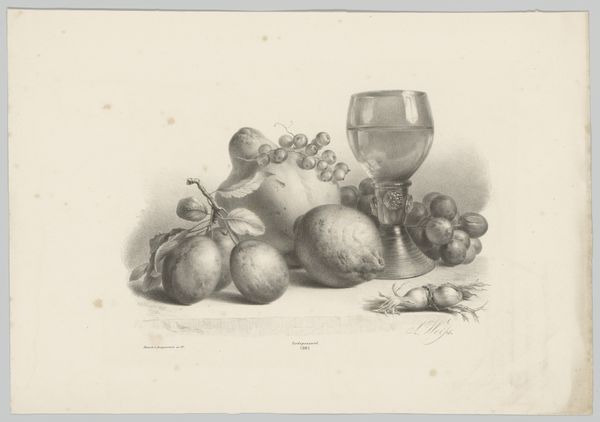

drawing, print, etching, graphite

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

etching

#

fruit

#

coloured pencil

#

15_18th-century

#

graphite

Dimensions: height 311 mm, width 473 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

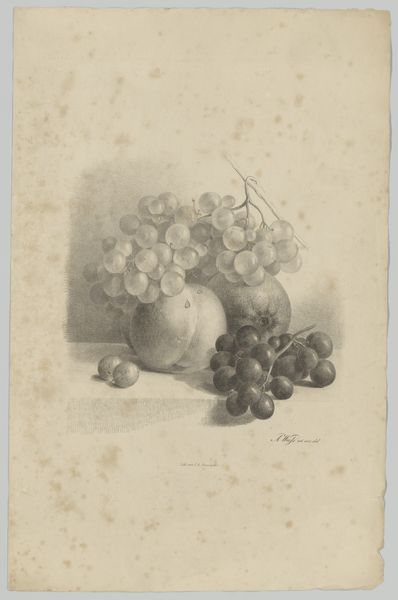

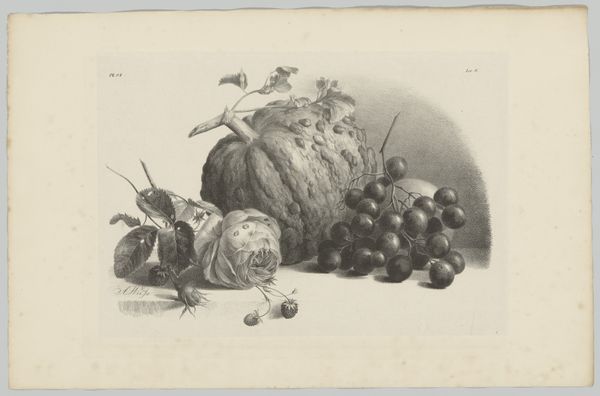

Curator: This drawing, "Still Life with Glass, Oysters and Grapes," dates from the first third of the 19th century, circa 1820-1833. The piece is on display here at the Rijksmuseum, rendered in graphite and etching techniques, which are expertly displayed across the page. Editor: The somber monochromatic palette gives a severe almost unsettling character. The composition seems staged—the glass, the oyster, the grapes… Are they symbols for something more? Curator: Considering the historical context, still lifes often served symbolic functions. Luxury items like wine and oysters can signify wealth, status, and a degree of global awareness of Dutch merchants and power. The Church might have been displeased. Editor: I wonder, though, about the deliberate choice of etching. Given that photography was still in its early stages, what message did the artist want to communicate? Did they see an inherent symbolism in reproduction itself? I'm thinking of the politics of the etching: Who had access, who reproduced them, and in what way were they sold? Curator: An intriguing angle, absolutely. The print medium would grant the artist greater reach. I wonder if they intended it for scientific study or simply aimed to appeal to collectors' aspirations for luxurious displays? Did wealthy patrons commission still life art like this for similar purposes? Editor: The grapes too--that bunch looks a little sickly, slightly rotten even. Perhaps the artist tried to comment on themes such as corruption. Curator: Could very well be. The decaying or vulnerability motifs of traditional paintings frequently reference our collective awareness about passing time and earthly decay, although these types of symbols tend to find favor among religiously inclined groups. But there could have been even more meanings implied as well. The relationship between mortality and feasting is often something found in still lifes as well. Editor: So it acts as a double-edged statement on class, taste, privilege, religion, nature, mortality, and commercial growth all in one seemingly innocent drawing. I'm also interested to think about the racial connotations and global trading networks in the colonies, that would bring all these items to the port and into people’s still lifes. Curator: A great analysis which offers layers and layers to discover as we look at the drawing, what do you think our modern day artists can glean from it? Editor: This reminds us of how we need to think when engaging art: to look, investigate, discuss, and consider from all possible viewpoints the function art played in broader social settings.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.