Chrysanthemum Festival- The Tamaya in Shin-Yoshiwara Edomachi itchōme c. 1830s

0:00

0:00

print, ink, woodblock-print

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 14 1/2 × 9 13/16 in. (36.83 × 24.92 cm) (image, sheet, vertical ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

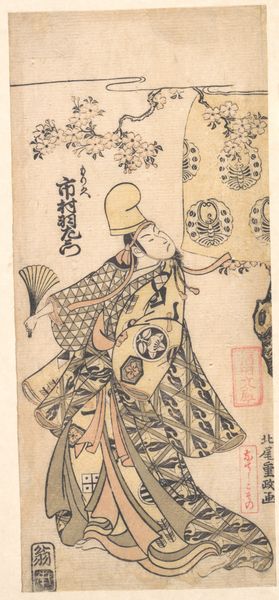

Editor: This is Utagawa Kunisada’s woodblock print, “Chrysanthemum Festival- The Tamaya in Shin-Yoshiwara Edomachi itchōme,” from around the 1830s. The texture of the paper and the vibrant colours make it feel incredibly tactile, almost like I could touch the patterns on the kimonos. What’s your take on this print? Curator: It’s fascinating to consider this print through the lens of its materiality. The very act of creating these prints was a collaboration, often involving publishers, designers, woodblock carvers, and printers, each contributing specialized labour. The type of wood used for the blocks, the quality of the ink, and the paper all influenced the final product and reflected a sophisticated consumer culture. What impact do you think this process has on the image's meaning? Editor: That's a side of artmaking I hadn't fully considered for prints before; the social network of artisans who each impart skill in a production line fashion. The print now seems less the expression of one individual and more a record of group labour. How does the festival setting relate to your analysis? Curator: Exactly! Consider the “floating world,” or *ukiyo*, depicted here. While seemingly about pleasure and entertainment, the festival setting speaks to the commercial forces driving Edo society. The chrysanthemums, symbols of longevity and beauty, become commodities displayed and consumed. The woodblock print itself becomes an artifact of this system, a tangible record of cultural exchange and production. The vibrant inks and detailed patterns, therefore, aren't merely aesthetic choices but also representations of the consumption and material wealth that characterized the era. Editor: So, you’re saying even the seemingly aesthetic choices reflect economic realities and a division of labour, very insightful. I'm struck by how a single print can reveal so much about the making, economy, and context in 1830's Japan. Curator: Precisely, analyzing the artwork from a materialist perspective exposes a deep web of economic, social, and labor relations which often go unseen with more traditional approaches.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.