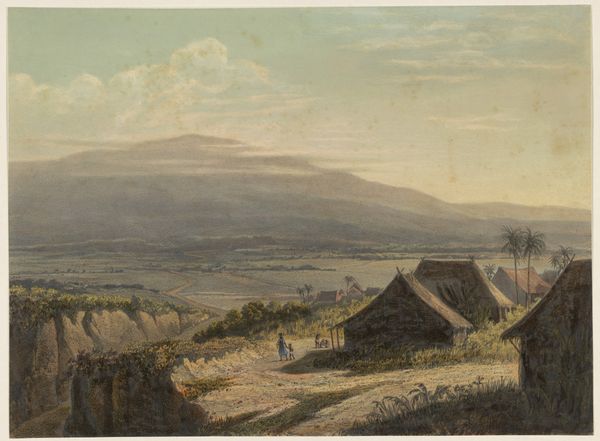

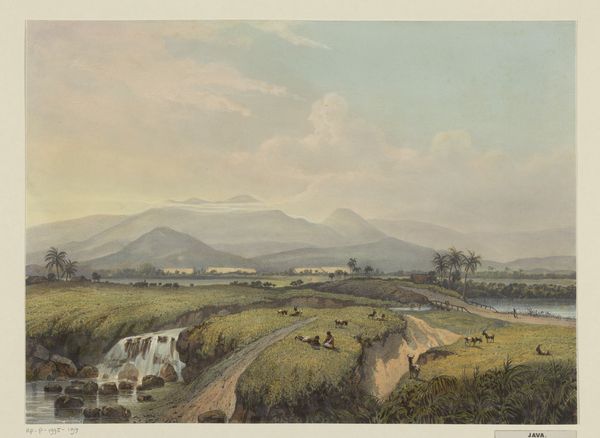

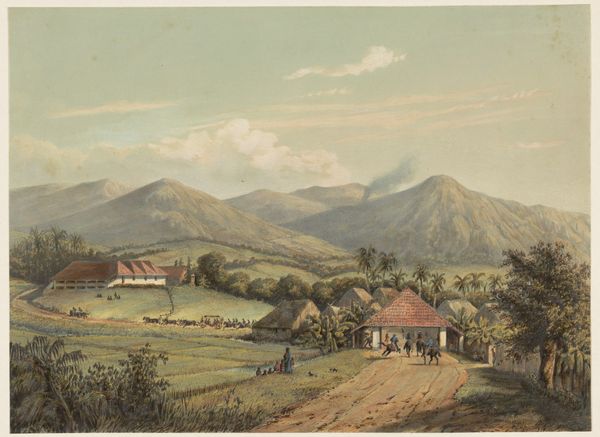

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 363 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This watercolor by Johan Conrad Greive, created in 1869, is entitled "Gezicht op Kedungbadak." It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is of quiet grandeur. There's this massive, almost imposing mountain softened by the muted tones and delicate brushwork. Curator: Exactly. The scene portrays Kedungbadak, now a suburb of Bogor in Indonesia, during the Dutch colonial period. Looking closer, one can notice laborers depicted very small on the side of the path to the left of the center of the frame. This contrasts the dominant depiction of nature and serves to normalize power imbalances in what was then the Dutch East Indies. Editor: Yes, the laboring figures become just another element, commodified within this sweeping view. You almost don't see them, overshadowed by the raw materials, the land that they must manage. There’s a tension, right? This is presented as an objective landscape, but it's completely mediated through a colonial gaze, even romanticized. What's particularly interesting is that it’s painted in watercolor, usually a medium associated with leisurely pastimes or sketches. But here it becomes this detailed record, part of an active strategy of ownership. Curator: I find it fascinating to view the watercolor, primarily seen as a feminine art-form and the production of it becoming this instrument of masculine domination. The way labor and nature blend subtly underscores how exploitation can be seamlessly woven into the perception of normalcy and even beauty. Editor: It is important to acknowledge that we may never know precisely what kind of exploitative work occurred there. Watercolor itself involves significant preparation, and like those of the invisible laborers, Greive’s work would eventually serve to fulfill some European patron’s desires, or perhaps an audience craving a taste of the exotic. And the consumption of such landscapes facilitated a connection to those territories, whether materially connected or merely ideologically complicit. Curator: Absolutely, a vital point, and it echoes beyond the purely visual, reaching into the ethics of production and the power dynamics ingrained within artistic representation itself. This painting and similar landscape paintings from this period become more poignant when we bring a more critical awareness. Editor: Seeing this through the lens of labor and materiality certainly forces me to think beyond the tranquil scene, and towards its complex origins and the relationships it perpetuates.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.