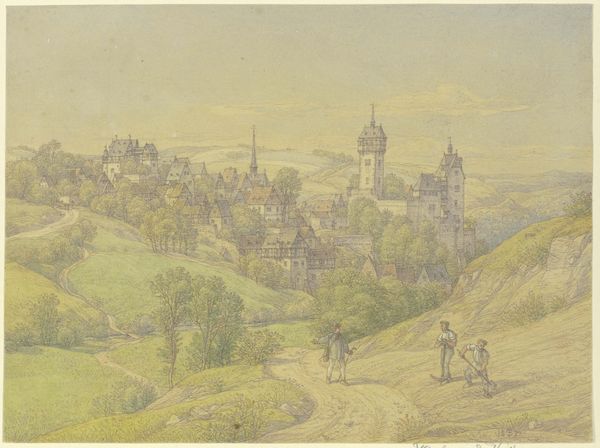

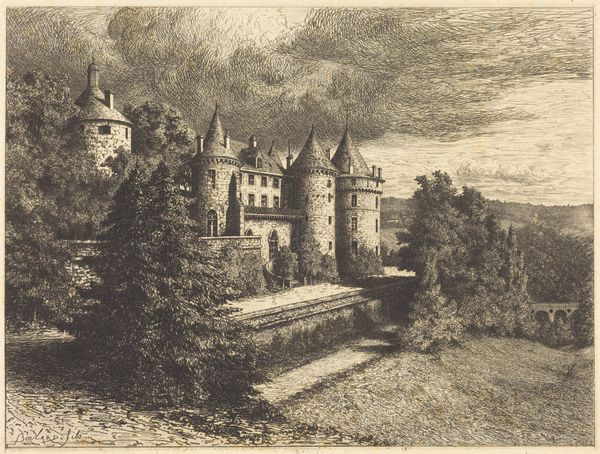

Gezicht op Lausanne, met uitzicht op de burcht en de kathedraal 1829 - 1911

0:00

0:00

henriknip

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 408 mm, width 585 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We’re looking at “View of Lausanne, with a view of the castle and the cathedral,” a watercolor work attributed to Henri Knip. The museum dates it vaguely between 1829 and 1911. I’m struck by the almost idyllic, staged quality of the landscape—it feels like a romantic backdrop for the figures on the path. What draws your attention when you see this piece? Curator: It’s fascinating how this watercolour captures Lausanne through a very particular lens. What appears idyllic to you, is actually a carefully constructed representation serving certain social and cultural functions. The placement of the castle and cathedral so prominently, against a somewhat soft and dreamlike landscape, elevates the socio-political and religious power structures within the town. Consider, who commissioned this work, and who was the intended audience? Editor: So, you're saying the seemingly innocent depiction of nature is more of a carefully curated…propaganda almost? Did landscape painting at this time often serve such purposes? Curator: Propaganda might be a strong word, but it certainly participates in image-making around power. Landscape painting in the Romantic period was frequently tied to notions of national identity and civic pride. Displaying a prosperous and stable town, anchored by its religious and military landmarks, communicated specific values and a sense of order. The relatively diminutive figures and animals on the road emphasize scale. Why do you think the artist included them? Editor: That’s interesting. Perhaps to reinforce the idea of everyday life happening under the auspices of these grand institutions? It creates a sort of implied endorsement. The town thrives under the watchful eye. Curator: Precisely. Think of the painting not just as a visual representation, but as a historical document reflecting and shaping societal values. How does understanding this impact your initial perception of the artwork? Editor: It definitely complicates it. What seemed like a straightforward landscape now feels much more layered. I see how the composition contributes to constructing a narrative about Lausanne’s identity. Curator: Indeed. It makes you question what is presented, and perhaps, more importantly, what is intentionally left out. Editor: Absolutely. It's fascinating how much historical context can reshape our understanding of even seemingly simple artworks. Thanks for helping me see beyond the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.