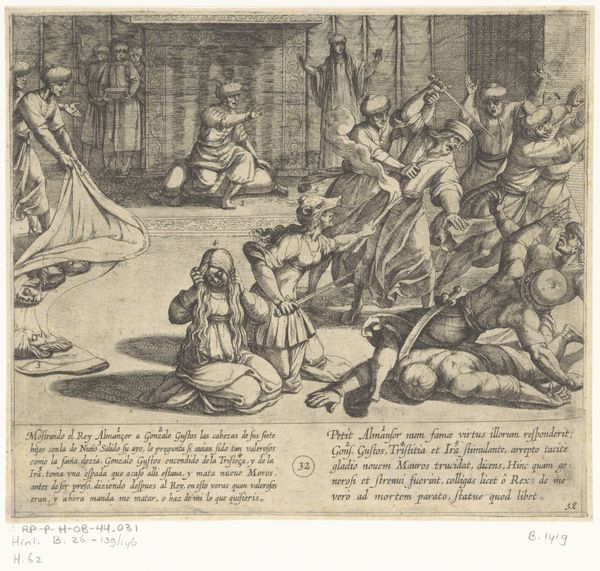

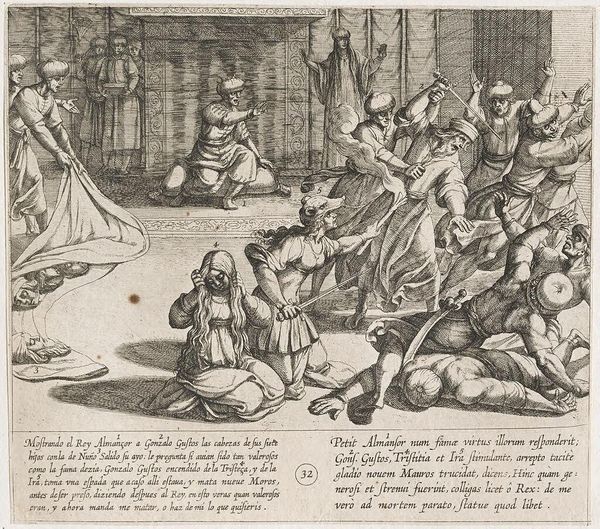

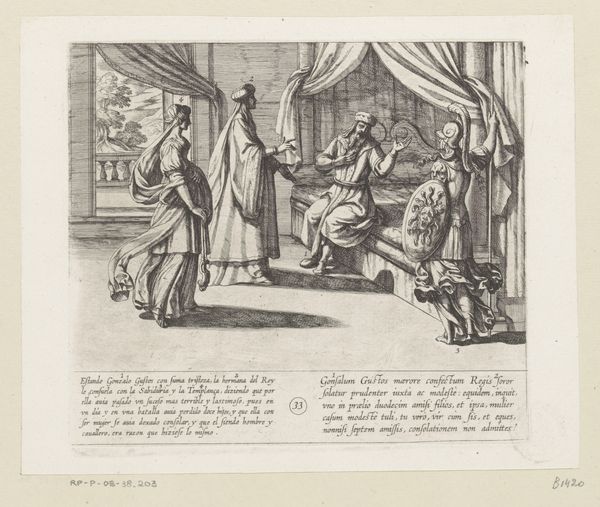

In aanwezigheid van Almanzor, identificeert Gonzalo Gustos de hoofden van zijn zonen 1612

0:00

0:00

antoniotempesta

Rijksmuseum

print, etching, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

islamic-art

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 206 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at the drama etched into this scene. This is Antonio Tempesta's "In aanwezigheid van Almanzor, identificeert Gonzalo Gustos de hoofden van zijn zonen," made in 1612. It's a print, specifically an engraving. Editor: It’s a stark image. Dark and filled with mourning. The presentation of severed heads is obviously intended to shock. What is the purpose? Curator: The artwork illustrates a cruel episode, a demonstration of power and brutality by Almanzor, an Islamic ruler, presenting the heads of Gonzalo Gustos' sons. Editor: I am interested in how Tempesta rendered such a specific episode in printed form for consumption and dissemination. Note the elaborate clothing, textiles, turbans… There's a clear attempt to portray an exoticized 'other,' reaffirming existing power structures. Are we sure we know what specific tools were used to produce it? And were the raw materials hard to come by at that point in time? Curator: That's interesting; the use of the printed image makes this political theatre, playing out the power dynamic in a way accessible to a wider audience than a unique painting would have. Tempesta utilized techniques that were quite involved to ensure the production, starting with careful etching of lines into the metal plate, adding details and textures to create depth, light, and shadow, then the plate would be inked to capture every detail and after being pressed on paper a complete work could be made from these careful procedures. Editor: So much of this era's artwork functions to reinforce specific political, racial, and religious viewpoints, wouldn't you say? I think about the history being narrated here, whose version gets centered, and what's obscured by this orientalist representation. Curator: Yes, there is an undeniable bias here, viewing it through a distinctly Christian lens, villainizing the ‘other.’ This also points to how this scene played within narratives constructing Christian identity at the time. Editor: Right. What Tempesta thought of 'Spain' or 'Christianity' definitely informed his creation! Considering art this way contextualizes the work, challenging how we might otherwise simply accept its historical depiction. Curator: Indeed, viewing this print is more than just looking at a historical record, but interrogating how narratives are made, distributed, and consumed within larger ideological frameworks. Editor: Exactly, understanding the conditions in which a piece like this emerged – that’s where true understanding lies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.