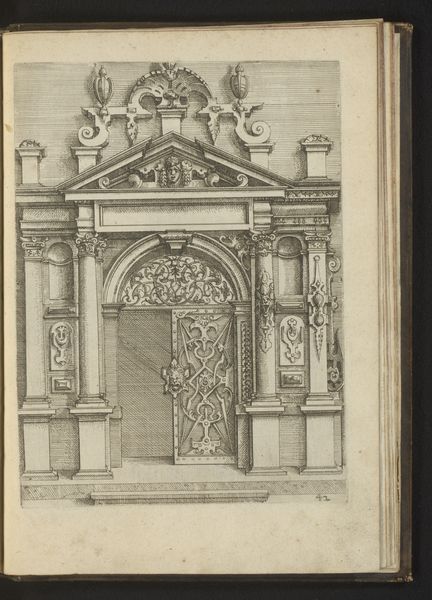

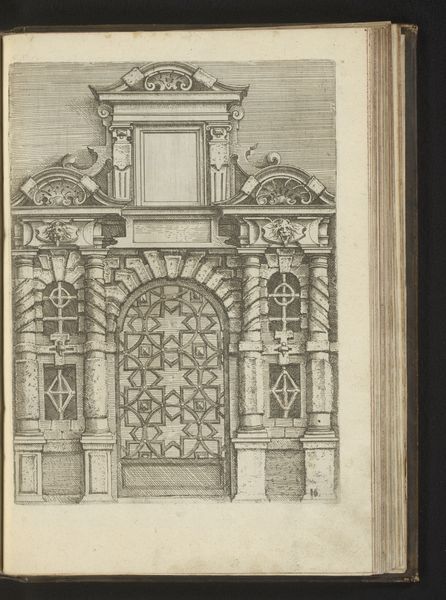

drawing, ink, pen, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

pen

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 254 mm, width 186 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

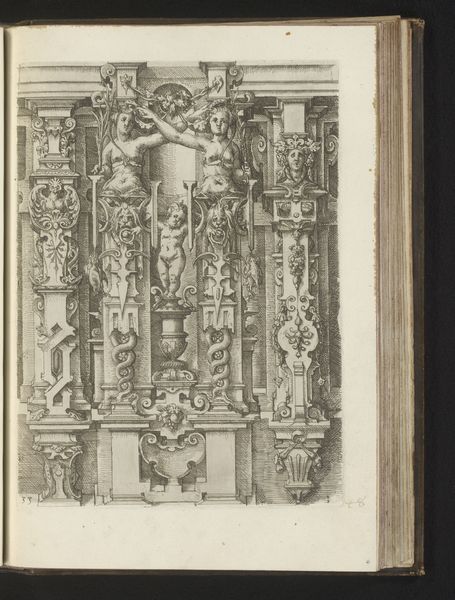

Curator: Just look at this! What do you see, walking up to this intricate design? Editor: An operatic dream of enclosure. It's imposing, detailed, yet ultimately a barrier. The heavy linework and the way it’s captured reminds me of a fever dream, that dizzying space between sleep and waking. Curator: Precisely. We're gazing upon a piece by Wendel Dietterlin, an engraving created between 1593 and 1595 titled “Portaal met ijzeren hek geflankeerd door kariatiden” or Portal with an iron gate flanked by caryatids. It showcases his unmistakable Mannerist style. Editor: Mannerist, indeed. The caryatids—female figures serving as architectural supports—feel almost strained under the weight of the structure, don't they? This really emphasizes the idea of women bearing societal burdens, quite literally holding up the gate and all its implications. I'm wondering if that was a deliberate artistic statement or if it simply speaks to our current moment? Curator: Well, Dietterlin's Mannerism played with exaggerated forms and spatial distortion to create a sense of unease, so that interpretation resonates beautifully. The detail, crafted with pen and ink, evokes grandeur, while those figures and ornamental ironwork also hint at exclusion and controlled access. Maybe all things that glitter aren't gold! Editor: Absolutely. The gate itself, so meticulously rendered, feels like a symbol of denied passage as much as an invitation. Who is kept out, and why? This portal screams hierarchy. And you have all these chubby putti hanging up above, like it is teasing those down below. Curator: The artist was obsessed with architecture, and this print reveals how he combined its elements to express philosophical, even esoteric, ideas about society, the world, and the human form. His vision was over the top, for sure, and it's thought to be intended to spark controversy! Editor: Mission accomplished, I’d say! It definitely evokes a dialogue, a tension between beauty and oppression that’s still relevant centuries later. It's an entry point not into a building, but a discussion. Curator: For me, its lasting appeal rests in Dietterlin's capacity to build up spaces which ask questions, offering us passage into speculation of how we think about power and beauty today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.