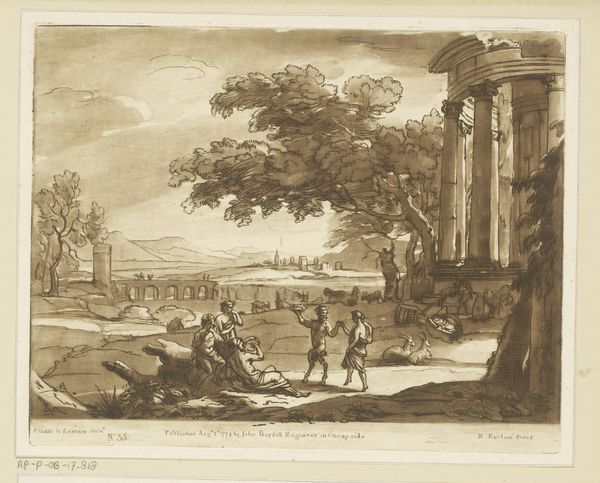

Landschap met herdersfamilie, ruïne en drinkende ossen Possibly 1776

0:00

0:00

richardearlom

Rijksmuseum

print, etching, engraving

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 206 mm, width 259 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

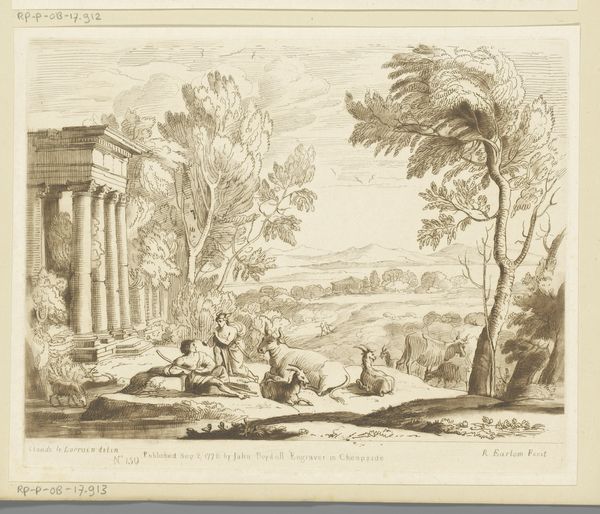

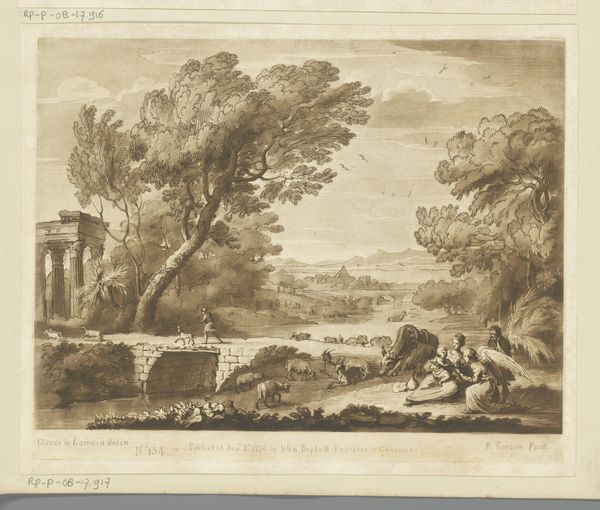

Curator: Richard Earlom created this print, "Landschap met herdersfamilie, ruïne en drinkende ossen," possibly around 1776. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum. What's your immediate impression? Editor: The sepia tones give it an aged feel, like a memory half-faded. The composition, though, is carefully constructed—the ruins on the left balancing the distant architecture on the right, drawing your eye through the landscape. Curator: The ruins are interesting, aren't they? They evoke a sense of classical history, perhaps Rome, even a lament for a golden age. These fragments act as potent symbols of past grandeur, speaking volumes about cultural continuity. Editor: Absolutely. But consider the materiality of that grandeur now, represented in print. We're not seeing marble; we are engaging with etching and engraving, a mass-produced image meant for distribution. The landscape becomes a commodity. Who could access such images, and what impact did this have on popularizing a vision of idealized landscapes? Curator: A keen point! Earlom, using etching and engraving techniques, makes classical imagery accessible, altering its context, and democratizing it through prints. Consider the etching, those delicate lines. Are they not reminiscent of sketching, blurring lines between original artwork and reproducible artifact? Editor: Exactly. It draws attention to the labor involved, the skill needed to replicate that Claudian aesthetic through manual, yet precise, techniques. It makes me think about the engravers themselves – what were their working conditions, who owned the means of production? Curator: Fascinating! And within the landscape itself, observe the positioning of the shepherding family near the ruin – they become integrated into history, participants in a landscape infused with symbolic significance, bridging the divide of eras. Editor: Yet their labor—the tending of animals, the use of land, and resources—becomes subsumed by this romantic vision. Are they laborers, picturesque figures, or both? That tension interests me. Curator: By delving into materiality and technique, you force us to reckon with the artistic processes that both produce and transform meaning, challenging conventional approaches that favor merely the aesthetic appeal of historical symbols and themes. Editor: Likewise, your emphasis on symbolic meaning underscores how these idyllic scenes naturalize the relationships between history, landscape, and labor that we ought to question, enriching the artistic dialogue in unexpected ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.