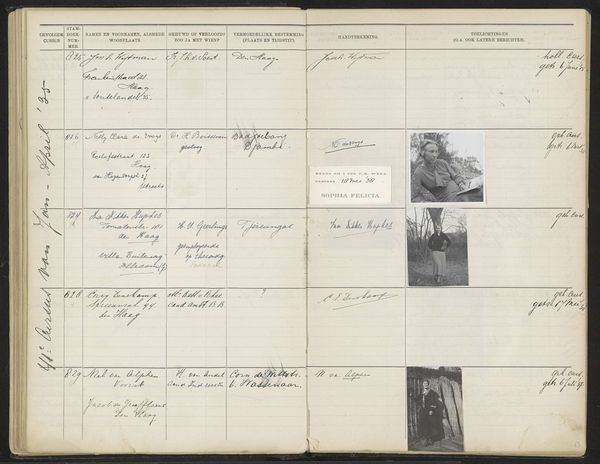

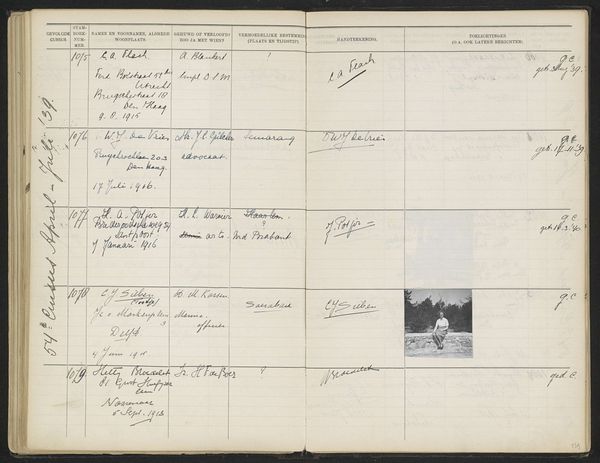

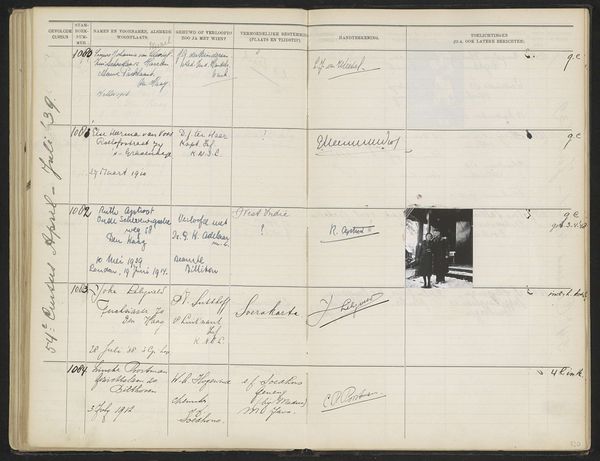

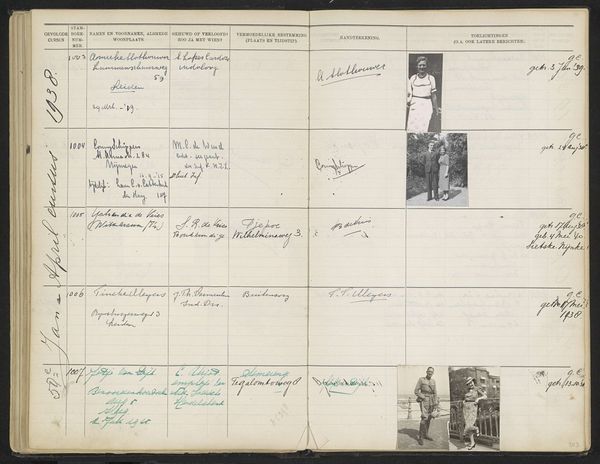

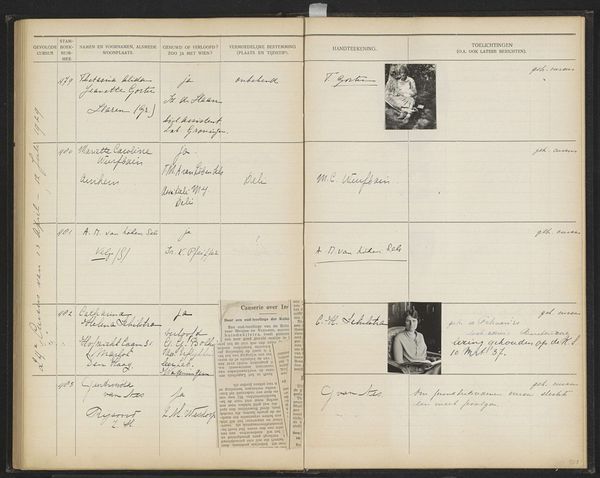

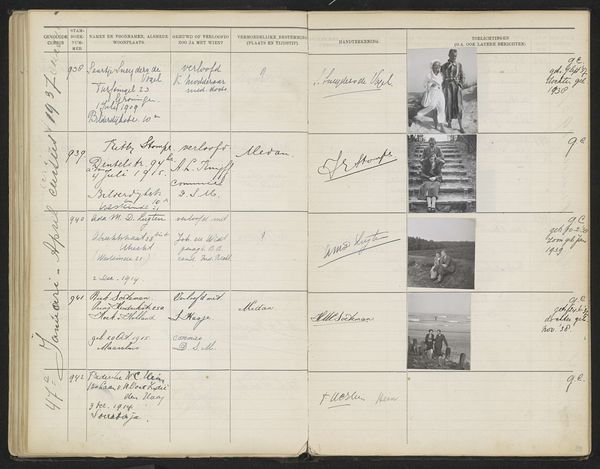

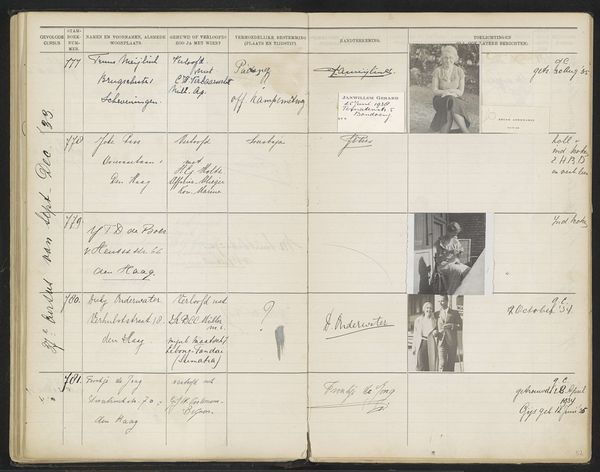

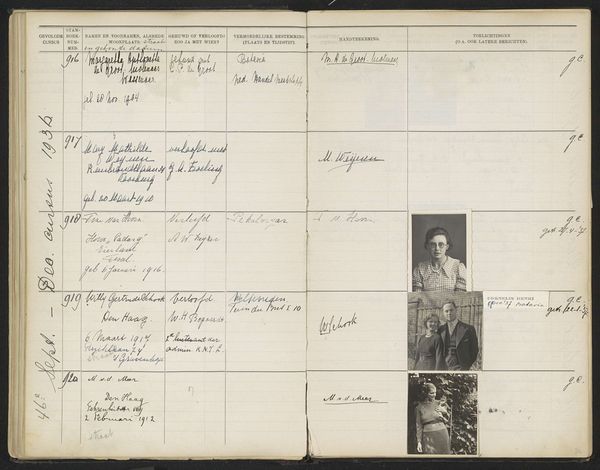

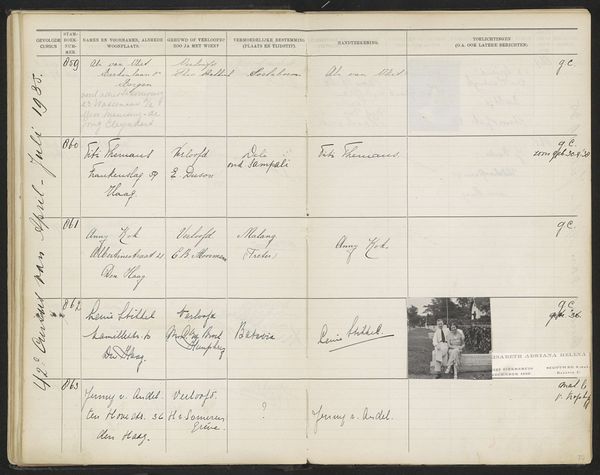

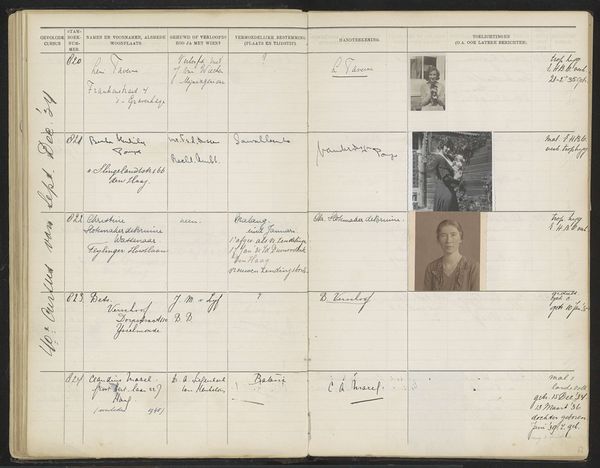

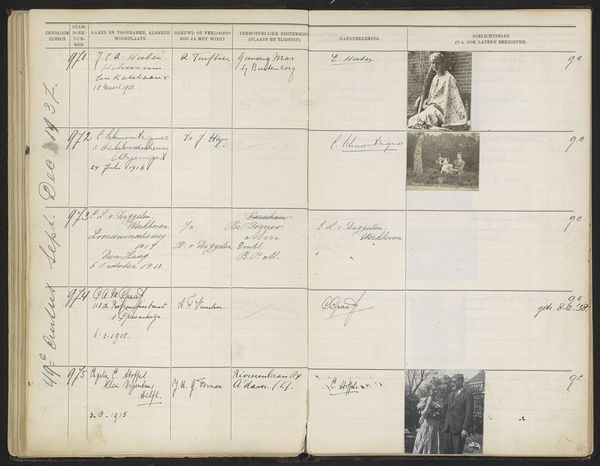

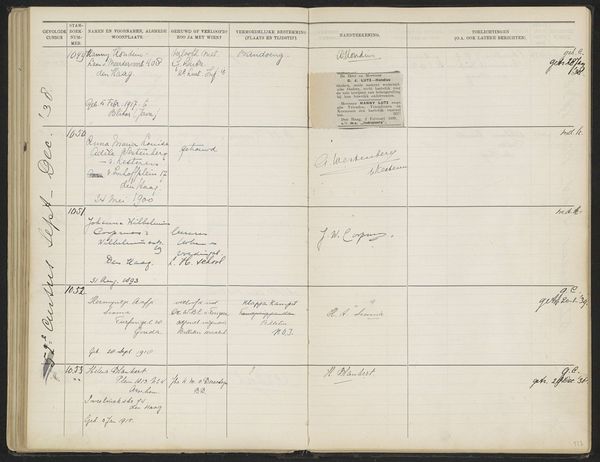

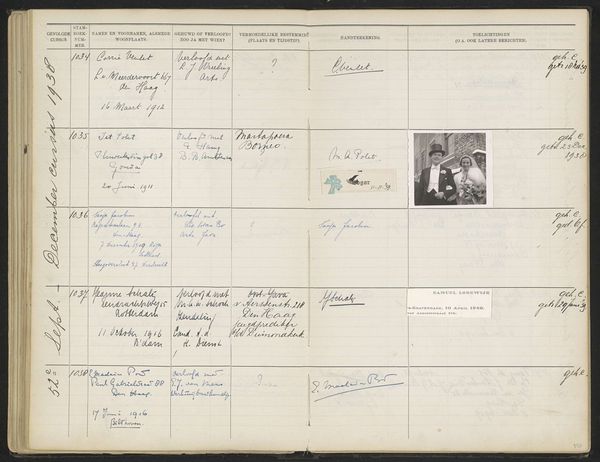

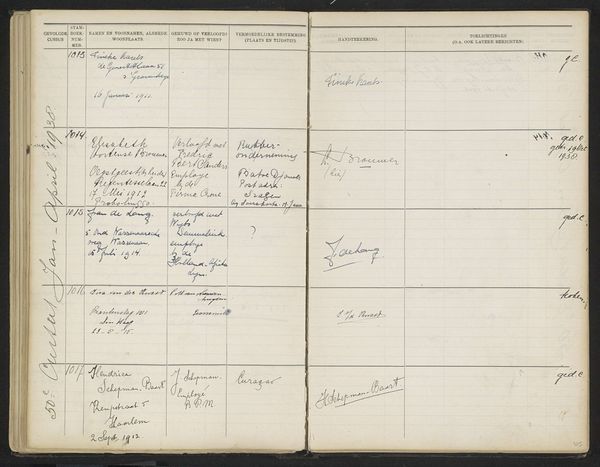

Blad 109 uit Stamboek van de leerlingen der Koloniale School voor Meisjes en Vrouwen te 's-Gravenhage deel II (1930-1949) Possibly 1938 - 1939

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

sketch book

#

hand drawn type

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-written

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

ink colored

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

academic-art

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 337 mm, width 435 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, what strikes you about this open page from "Blad 109 uit Stamboek van de leerlingen der Koloniale School voor Meisjes en Vrouwen te 's-Gravenhage deel II (1930-1949)"? It's a spread from what seems to be a student registry or yearbook, possibly dating from 1938 or 1939. Editor: My first thought? It feels incredibly… intimate, yet institutional. The neat rows of hand-written entries contrasted with the personal photos pasted in the "handtekening" column create an intriguing tension. It speaks volumes about control and individuation, or a twisted attempt to suggest control. Curator: Precisely! Think of these young women, perhaps preparing for lives of service in the colonies. Each entry meticulously records their name, origin, previous place of residence… It’s all quite regimented. And the attached photographs serve as these eerie individual identifiers, each unique yet trapped in the same frame. Editor: Right, the archive is interesting to think through because it immediately raises questions of identity, gender, and empire. What does it mean to be schooled specifically as a woman for colonial service? What kind of expectations are placed upon them? Curator: Expectations that were most certainly coded within this school, and later on the people this institution molded to represent colonial structures. We're also viewing it decades later. We know these archives represent more than their apparent bureaucratic task. There's this haunting aspect too… who were these women? Where did they end up? What did they do with their education? What was left unwritten? Editor: Absolutely, those unwritten narratives haunt the archive. You think about the colonial project's insidiousness – how it sought to erase or overwrite existing histories and identities. The very act of documenting these students in this way is a form of control, and frankly violence as well, whether realized by those recording this in the archive or not. And photography at the time, while it may seem like something casual to the viewer in the 21st century, for a majority of these young women, this may be one of very few photograph of themselves. A luxury many may never have been able to afford on their own without being provided by the state. Curator: Looking at this brittle paper is almost like staring through time. One is a silent witness, perhaps? The mundane documentation reveals cracks in the facade of order and control. The beauty and cruelty are palpable; I can practically smell the ink in the aged binding of the registry. Editor: Right? We get to engage with that legacy through the archive's survival – a fragment inviting critical reflection of gender, identity, and power. I want to explore this collection, or rather… unearth this collection. It is really vital in the field of research for further insight.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.