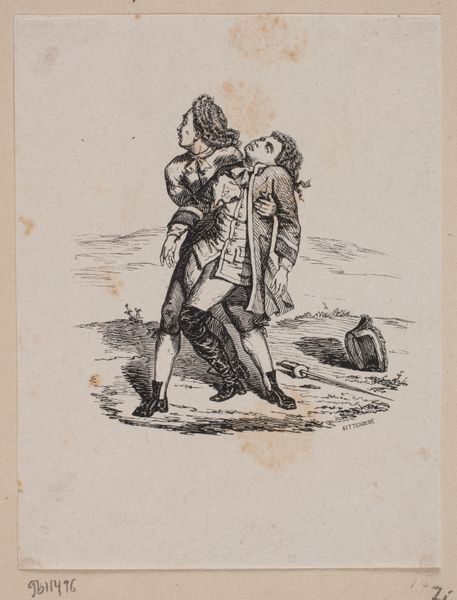

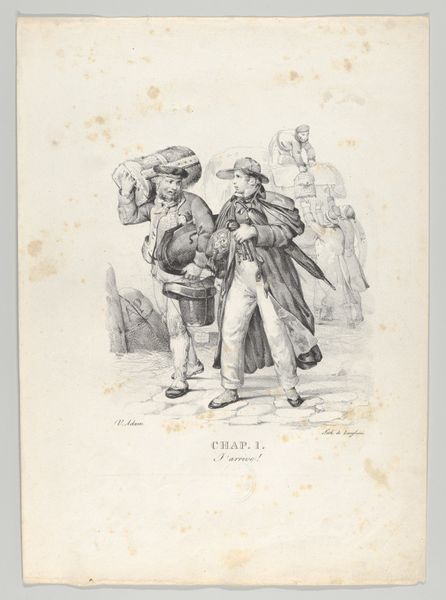

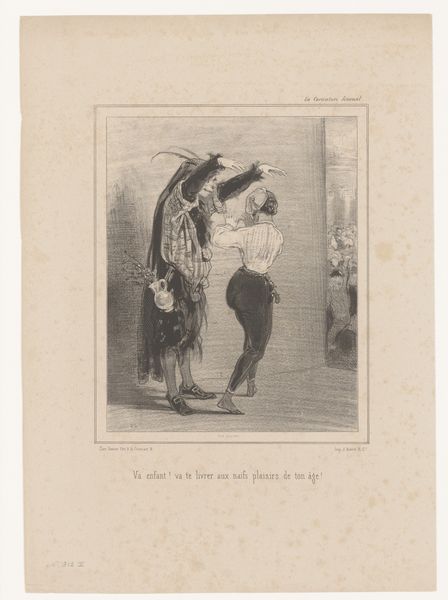

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 257 mm, width 181 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We're standing before Paul Gavarni's etching from 1840, "Pivonnet wordt weggesleept uit een café," housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Well, my initial impression is of the sheer physicality. The brute force! The larger figure hoisting the other so effortlessly... it feels both humorous and slightly unsettling. Curator: Precisely. Note how Gavarni employs etching to capture the raw emotion of the scene. The frantic, almost chaotic lines lend themselves to this sense of disarray and urgency. See, too, the formal contrast: the sturdy form of the person carrying, the limp, almost broken figure being carried away. Editor: The way that limp figure is rendered intrigues me. Is it indicative of a complete lack of agency, perhaps reflecting some sort of social commentary on dependence or a critique of the consequences of excess? I imagine this etching would have circulated quite widely at the time. Where might someone have viewed this? Curator: Likely in publications of the day, affordable prints that delivered political or social critique. Etching allowed for multiples. The act of producing images to make pointed commentary reflects how print became the media of dissent. Editor: It's quite captivating how the etching medium—relatively quick, certainly less precious than oil on canvas—allows for immediacy and dissemination. You're right, I see echoes of political dissent! The rough textures almost mirror the rawness of societal tensions simmering just beneath the surface. Curator: Yes. Look, for instance, at the figure’s clothing: its detailed portrayal, achieved through layered lines, communicates wealth. Conversely, the one being carried is far less meticulously drawn—simpler lines suggesting a lack of importance, a marginal place within society. Editor: Fascinating, considering its intended role and broad accessibility. It almost seems subversive, blurring the line between high art and what we might consider popular illustration. A commentary meant for popular consumption. The very nature of its materiality speaks to its message. Curator: Indeed, Gavarni uses visual language to navigate complex social dynamics, laying bare the uneven terrain of power and privilege within a seemingly simple genre scene. It invites inquiry into social production and how such themes end up for view by various classes. Editor: Thinking about the physical act of its making, it does bring to the forefront of the conditions of artistic creation itself, where each line applied onto the plate carried within it social implications. Food for thought indeed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.