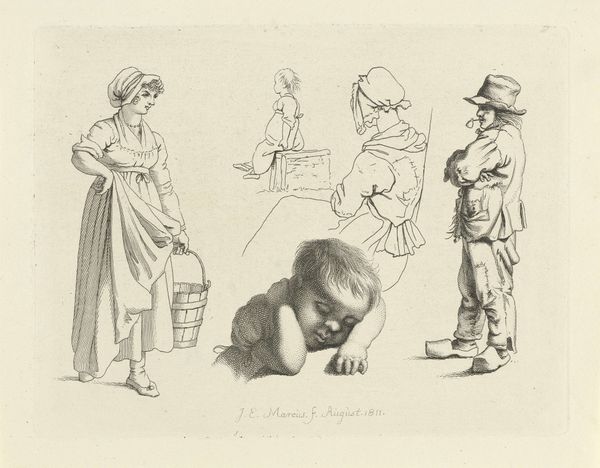

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

graphic-art

#

allegory

# print

#

line

#

engraving

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 201 mm, width 306 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is “Schilderkunst,” made between 1750 and 1778. It’s an engraving by Georg Leopold Hertel, housed at the Rijksmuseum. It depicts cherubs around art supplies. I find it interesting how these cherubs are actively working—what story do you think the work is telling? Curator: From a materialist perspective, I am more concerned with how it reveals the infrastructure of artistic production in the 18th century. Consider the engraving technique: a meticulous, labor-intensive process that democratized images and brought art to a wider, consuming audience. Who could afford this print? What does its relatively small scale say about how people accessed images at this time? Editor: That’s interesting! So, it’s less about the cherubs themselves and more about the availability and production of art for the common person? Curator: Precisely. We see how the Rococo style, with its delicate lines, was reproduced and consumed through printmaking. This engraving acts as a commodity itself, divorced from the presumed originality of painting. Also note how printmaking creates a lineage through reproduction—this image is based on a drawing by F. Boucher, a successful painter from the Royal Academy. Editor: So, the "high art" of Boucher is transformed by the labour of Hertel's "low art" printmaking. Curator: Exactly. How do you think the availability of such prints might have shaped artistic taste and demand at the time? Editor: I hadn’t considered that! The means of production truly shaped access to and the understanding of art. Thanks, that shifts my perspective entirely! Curator: Mine too. It's helpful to recall the concrete materials of image-making and think about how consumption changes meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.