Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

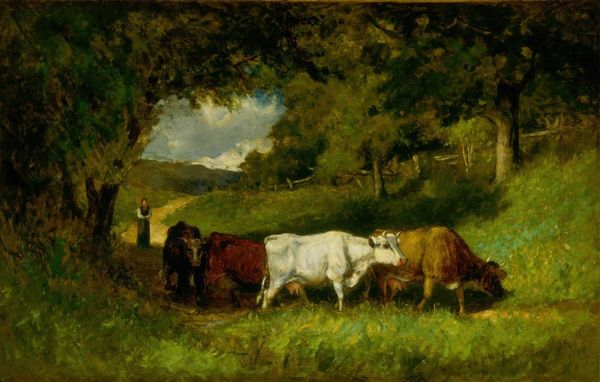

Curator: There's a lovely tranquility in Eugène Boudin's "Environs d’Honfleur," painted sometime between 1854 and 1857. It’s an oil on canvas depicting a pastoral scene near the coastal town. Editor: My first impression is one of a gentle realism, the soft greens and browns creating an incredibly earthy, material presence. I find myself focusing on the handling of the paint itself, a subtle choreography between thick impasto and smooth glazing. Curator: Absolutely, and consider how that palette evokes the traditions of landscape painting. But look also at the scene’s content: The cattle, the figures on the path, aren't merely picturesque. Cows have long held complex associations, particularly fertility and nourishment. They connect to the land itself, speaking to cycles of production and sustenance. Editor: True, and it also suggests a society built on agrarian labor, on the material process of animal husbandry. I'm drawn to how Boudin captured this life in paint, the labor embedded in the very materiality of the artwork itself. It is made by and of work. Curator: Indeed, yet there’s a romanticism, a gentle idealization here as well. That distant water in the painting invites contemplation, providing a vista toward escape and possibility. How does this interplay affect its lasting resonance, do you think? Editor: Perhaps because Boudin has documented not only an ideal, but an active economic engine tied to location and people—it provides a social and environmental image of 19th century Europe. We might miss these connotations in more “elevated” subjects of art. Curator: The symbol becomes richer through the dirt and labor. Editor: Yes. What begins as picturesque extends towards social documentary. Curator: I think my understanding of the symbolic implications in the work is increased. Thank you. Editor: Likewise; materiality can expand the symbolic significance of even simple landscape scenes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.