drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

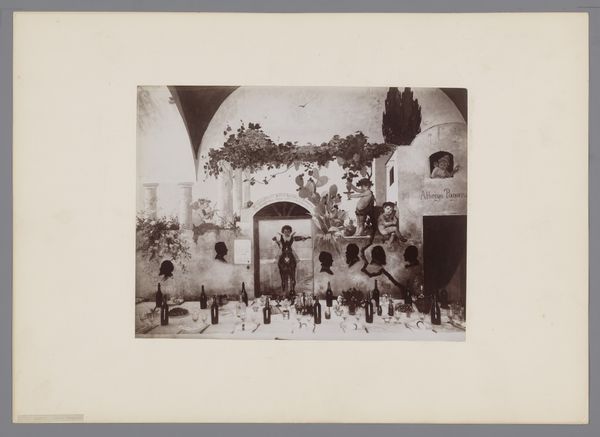

archive photography

#

old-timey

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: height 247 mm, width 319 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

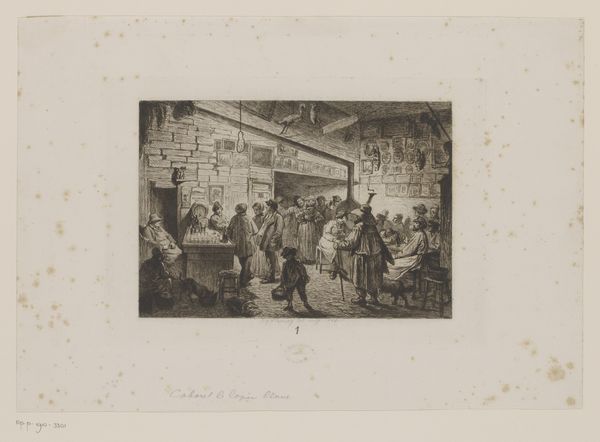

Editor: So this is "Ter dood veroordeelde man," or "Condemned Man," by Léopold Flameng, made in 1870. It's an etching. It's intensely melancholic. What really strikes me is how the faces tell so many different stories within the same setting. How do you interpret the symbolism in this piece? Curator: It is heavy, isn't it? What jumps out at me are the cultural symbols embedded in this image, such as the gathering around a final meal—a ritual reminiscent of religious iconography and, of course, the biblical Last Supper. There's also a suggestion of performance. Notice how the condemned man is staged. There’s an audience present, almost like theater. Do you think this amplifies the drama or perhaps comments on the nature of public punishment itself? Editor: That's a fascinating point about performance. It does feel very staged, as if we are watching a play. It almost desensitizes the gravity of the moment. Curator: Exactly! And what about the figures surrounding him? Consider the symbolism of children present. Are they witnesses to history, or victims of it? Their innocence juxtaposed against the impending doom highlights the emotional complexity Flameng captures. What does their presence evoke for you? Editor: It evokes a sense of broken innocence, of the corruption of childhood by witnessing something so cruel. They represent not just present sorrow, but also a future haunted by this memory. Looking at it again, I notice how the man's head, seemingly already severed on the floor, adds an element of brutal honesty, pushing through the layers of staged sentimentality. Curator: It does. That head transforms the domestic scene into something grotesque, reminding us that images can hold cultural trauma, prompting both mourning and critical reflection. This piece offers such fertile ground to examine how historical events shape collective memory. Editor: I agree. I didn't think of how much a single image can say about cultural memory, the weight of it, until now. Curator: Yes, art allows us to visit the past, to reckon with what was, and to question what still is.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.