drawing, print, paper

#

drawing

#

type repetition

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

script typography

# print

#

hand drawn type

#

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

orientalism

#

thick font

#

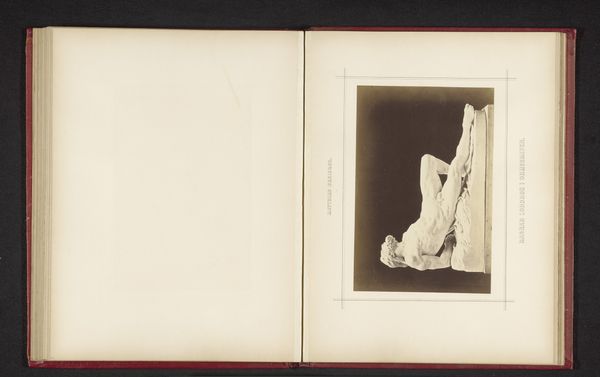

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

historical font

#

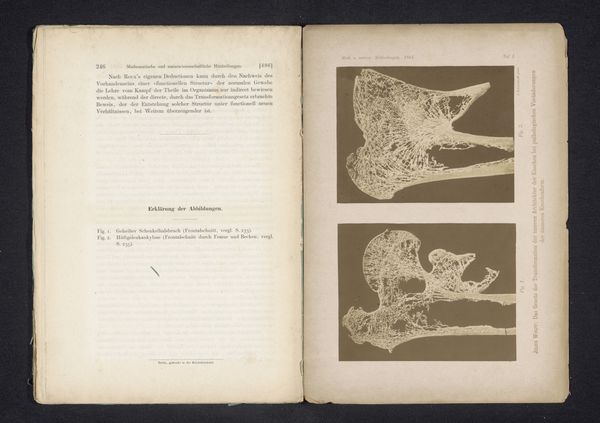

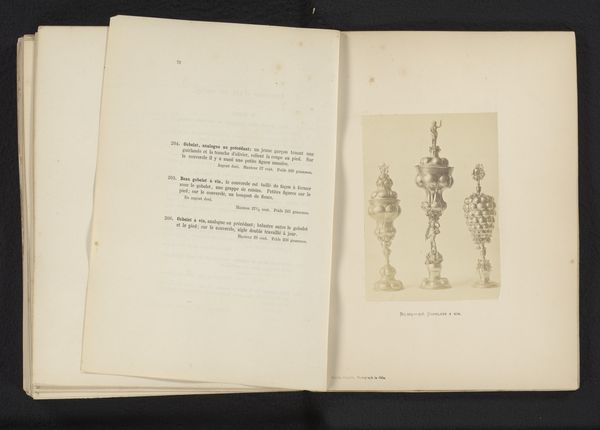

columned text

Dimensions: height 204 mm, width 159 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

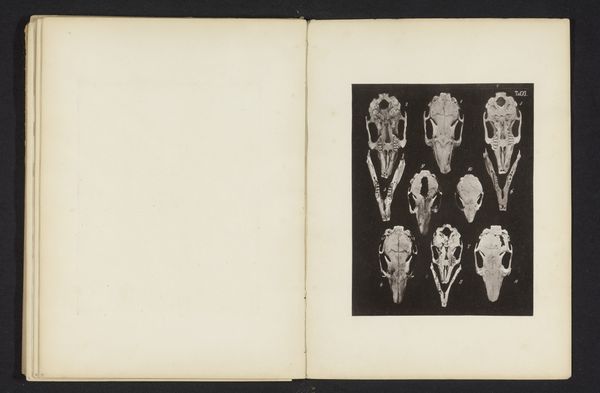

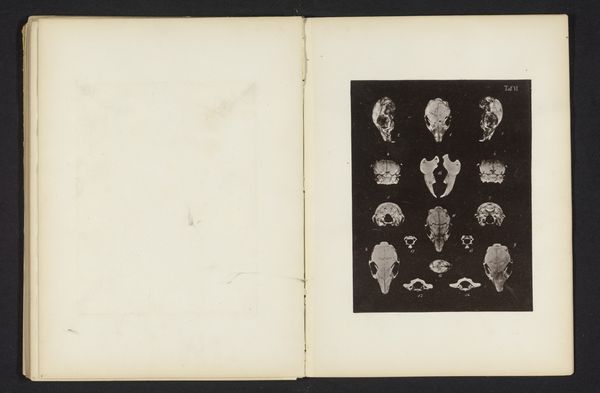

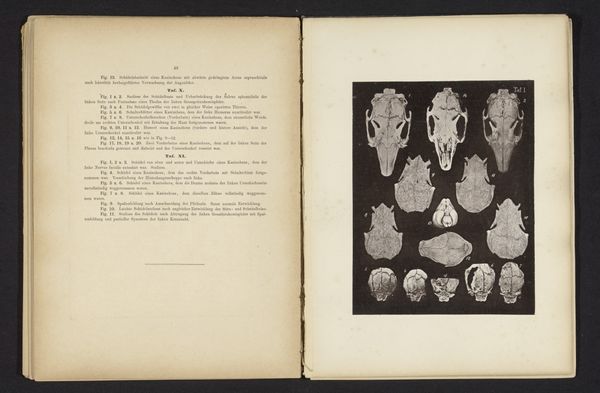

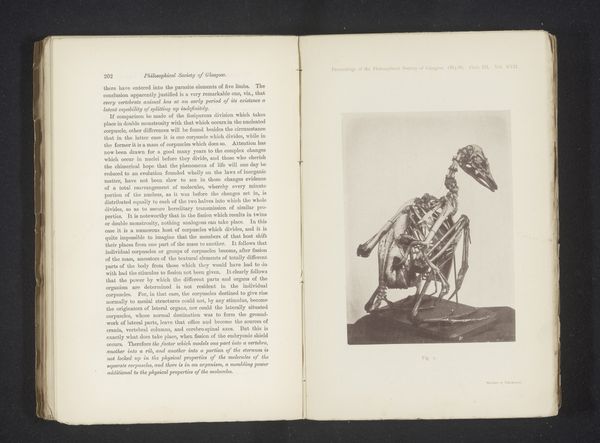

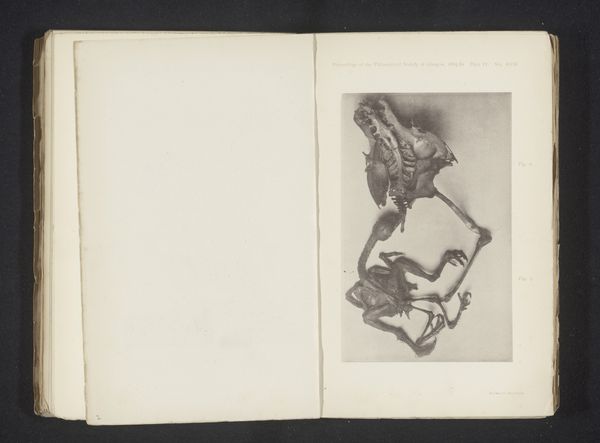

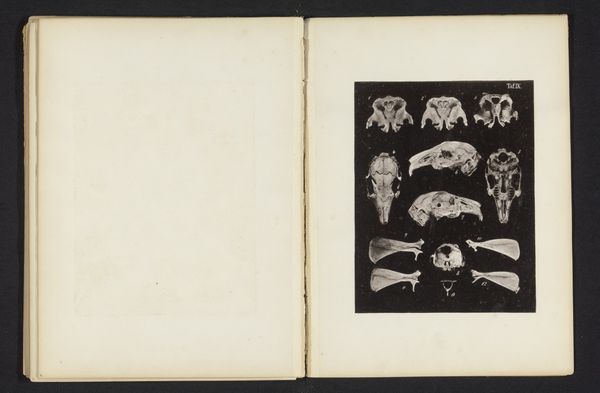

Editor: So, here we have "Twintig aangezichten van botten en het schedel van een konijn," or "Twenty Views of Bones and the Skull of a Rabbit," created before 1874 by Bernhard von Gudden. It's a print, almost like a page torn from an old textbook or personal sketchbook. I'm struck by the stark contrast of the bones against the dark background and how meticulously each piece is rendered. What do you see in this piece beyond its apparent anatomical nature? Curator: What immediately strikes me is the work’s engagement with systems of knowledge and power. Think about it – who gets to dissect, study, and categorize? During the 19th century, this act of naming and classifying was deeply intertwined with colonialism and the assertion of Western dominance. The rabbit, seemingly innocuous, becomes an object subjected to scientific scrutiny. Does that raise any questions for you? Editor: Absolutely. The objective "scientific" gaze isn't so objective after all. The very act of isolating these bones speaks to a specific, perhaps biased, way of seeing the world. So, how might that colonial context influence the way we view this image today? Curator: We must acknowledge how images like these participated in creating a hierarchy. On one hand, we can interpret the detailed rendering of each bone as demonstrating the value of science. Yet, it also implicitly asserts power over the natural world, turning living beings into objects of study. It invites us to question whose knowledge is valued and whose perspectives are marginalized in such depictions. Does it remind you of other scientific studies of the period? Editor: Yes, thinking about phrenology and the pseudoscience used to justify racial hierarchies... I see the connection much more clearly now. This wasn't just about bones; it was about solidifying a worldview. I now realize this image asks far more questions than it answers! Curator: Precisely. It's a potent reminder that art, even scientific illustration, exists within broader social and political currents. Hopefully, this exercise makes us all the more critical!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.