Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

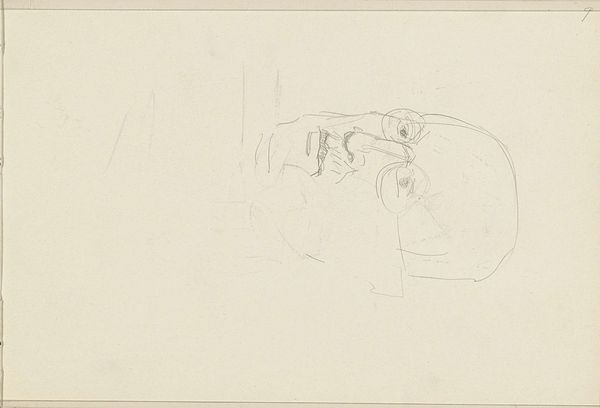

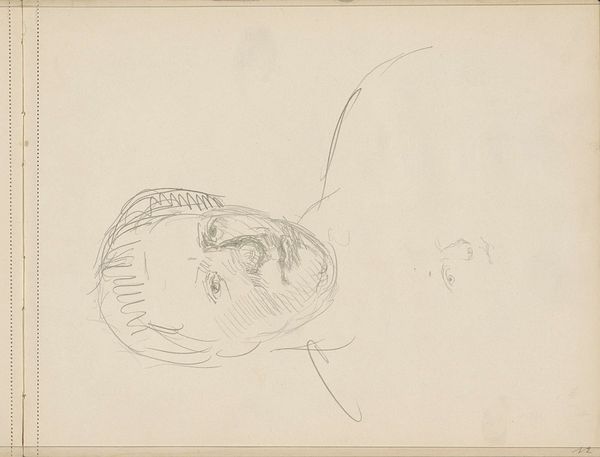

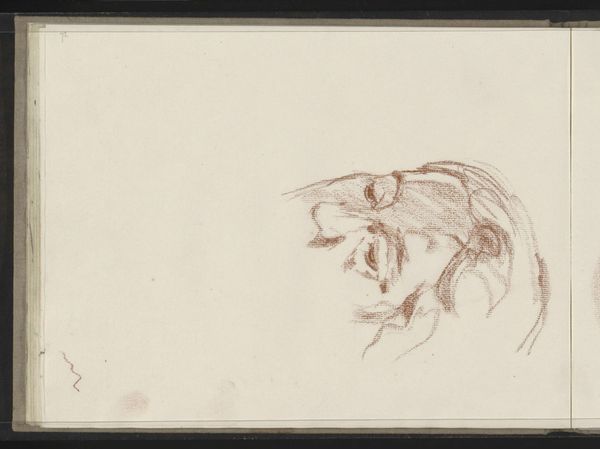

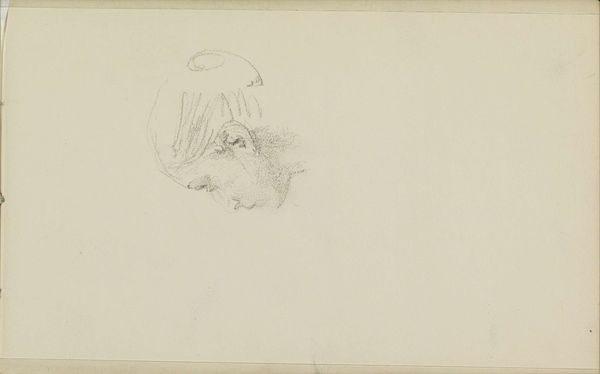

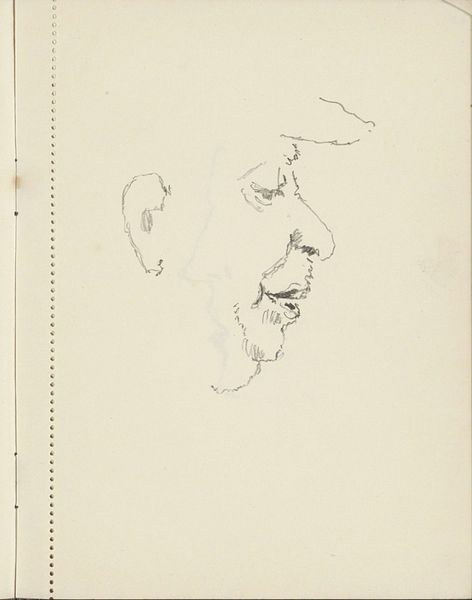

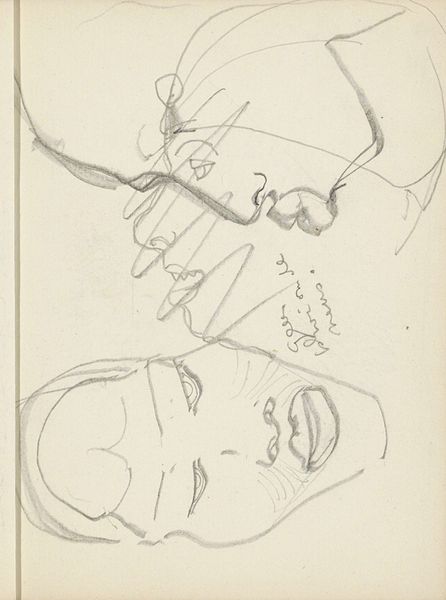

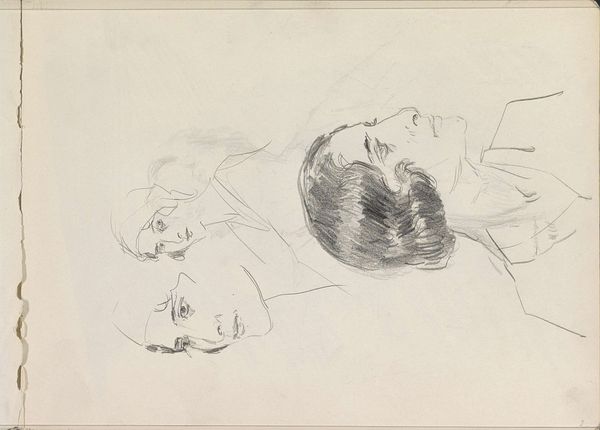

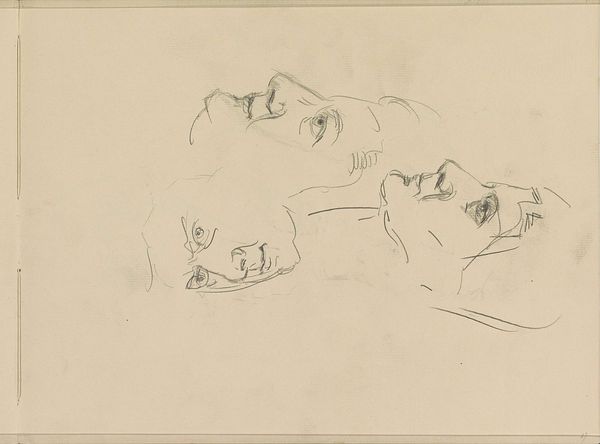

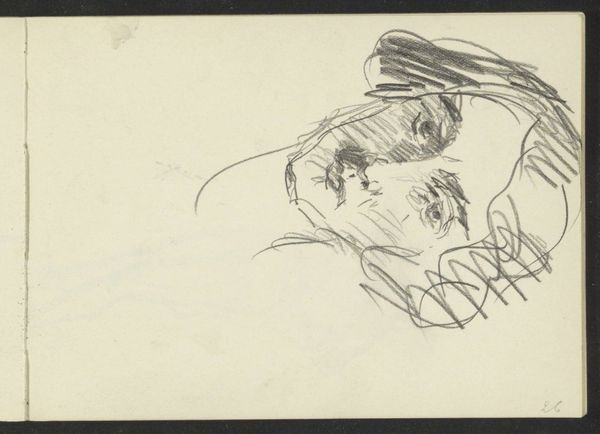

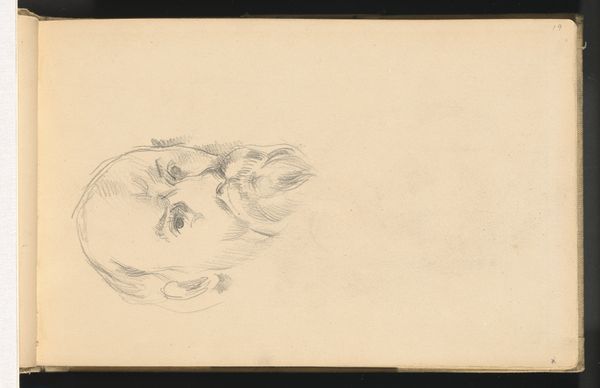

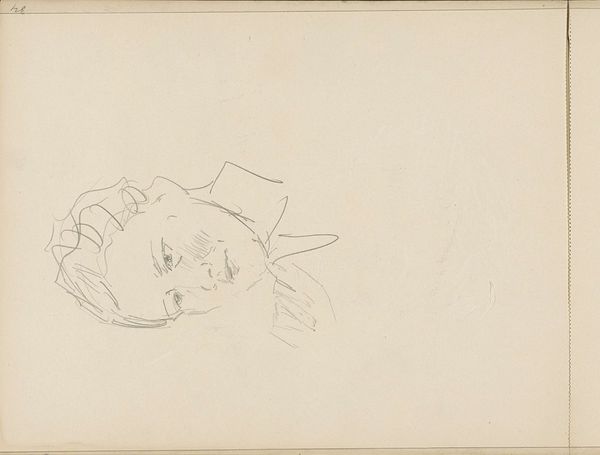

Curator: Here we have "Vrouwenhoofd en een zelfportret van Isaac Israels," a pencil drawing by Isaac Israels, created sometime between 1875 and 1934. Editor: There's something almost ghostly about it, isn't there? Just the faint, sketched outlines...like catching a fleeting memory. I suppose it’s fitting for a self-portrait—artists peering into themselves. Curator: It is more than one peering, yes. On a very tactile level, observe how Israels employs the pencil. The rapid strokes suggest immediacy; he's capturing an impression rather than a precise likeness. Look at the materiality – a relatively simple tool to explore the complexities of identity and representation, but it's so very raw and honest. Editor: I find myself wondering about the economy of line, really. What made Israels decide what to include and what to leave out? The sketch of the woman almost seems secondary to the self-portrait – did he draw that from his mind or from someone in front of him? And I cannot help but consider the economic conditions of being an artist and what the act of portrait making or drawing signified at that moment. Curator: I love that reading. The Dutch Golden Age had ended by then. One senses his effort in trying to balance tradition with modernity. The simplicity of line juxtaposed against such intricate study hints that it might have been done swiftly, perhaps even in one sitting with little to no modifications! Editor: Or perhaps, you could see how those portraits were replicated later, used to solidify identities and roles. Were those self-portraits or portraits of people replicated by prints in local magazines or distributed to their close community and friends? Were they for selling? Maybe he found pencil appealing because it was a versatile, easily sourced medium. Think about the socioeconomic implications and its impact on circulation. Curator: It is that, precisely! These rapid drawings almost act like cultural and commercial objects in their simplicity, or perhaps prototypes of grand oil paintings later in life. I wonder if those rough pencil drawings allowed others from outside to peer into intimate circles. Editor: Absolutely, each stroke speaks to a broader story about the social context of portraiture itself. How exciting that the economy of art might have shaped its material form. It feels like looking into an unfinished conversation between art, commerce, and self. Curator: Indeed, what’s been revealed feels all the more genuine. And what has been omitted or left undefined makes me ponder what other stories are in between the strokes!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.