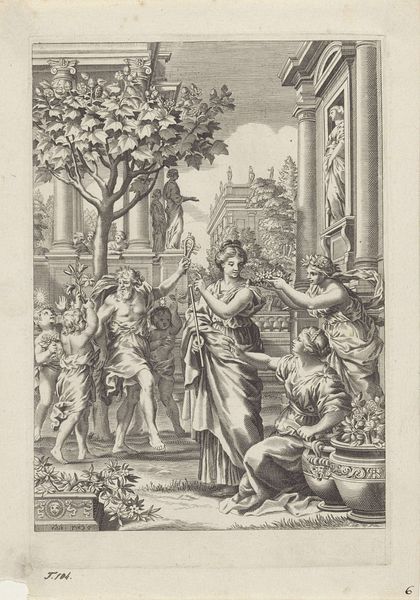

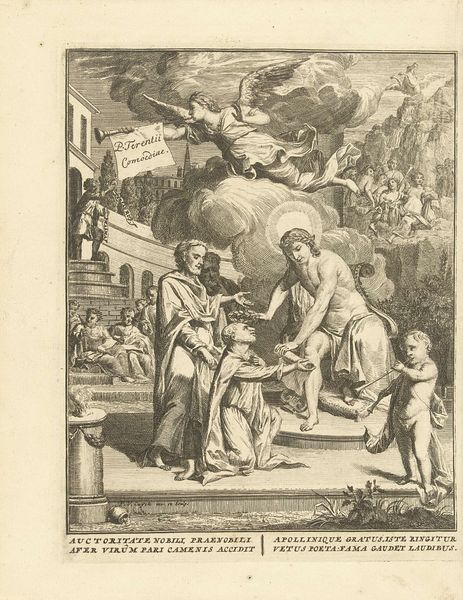

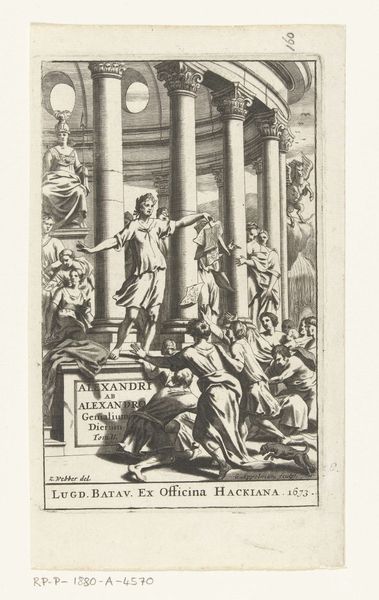

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

pen illustration

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 142 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The Rijksmuseum holds a striking engraving titled "Prints of the Female Reproductive Organs," created in 1672 by Hendrik Bary. It's quite a piece! Editor: My first impression is one of cool detachment, actually. Despite the allegorical nudes and putti, the overall feeling is clinical and almost austere. There's a neoclassical chill to the rendering of form. Curator: Precisely! Remember, this was produced during a period of intense scientific inquiry and the rise of anatomical illustration. It accompanied a published thesis related to female reproductive organs and generational theories from Reinier de Graaf. Editor: The contrast between the softness of the figures and the linearity of the engraving is compelling. Bary used hatching masterfully to delineate volume, which adds visual texture and detail, right? The way the light seems to skim over the allegorical woman's form is captivating. Curator: Absolutely, and that relates to the era. Scientific discovery was often presented through the lens of established aesthetic norms, creating complex narratives about knowledge, the body, and societal roles. These prints had both scholarly and social implications. Editor: Notice the architecture receding in the background – it suggests a distant civilization observing this act of reproduction. The details in the tree canopy too, convey the meticulous precision required for anatomical study at that time. The entire picture is perfectly organized by the rule of thirds, very classical, which provides its structural balance. Curator: I agree. Its style aligned the pursuit of medical science with classical virtues and societal ideals. Bary wasn't merely rendering organs; he was presenting an understanding of reproduction within a framework of allegory and scholarly discourse. Editor: Ultimately, seeing it through our contemporary eyes—it’s strangely captivating, and unnerving. Curator: It challenges us to contemplate shifting societal attitudes about gender and science. Thank you for taking the time to engage with me on that. Editor: A fascinating convergence of science and art, indeed. It provides much insight on its era and cultural underpinnings.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

In 1672, physician and anatomist Reinier de Graaf published his De mulierum organis about the female reproductive organs. The book contains detailed prints by Hendrik Bary, among them several of the vagina. De Graaf was the first to conclude that a foetus was the product not just of a man’s seed, but also of a woman’s egg. He discovered what he called blisters, which later became known as Graafian follicles.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.