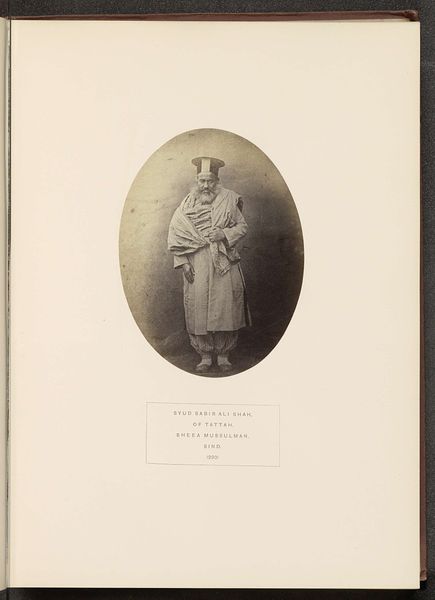

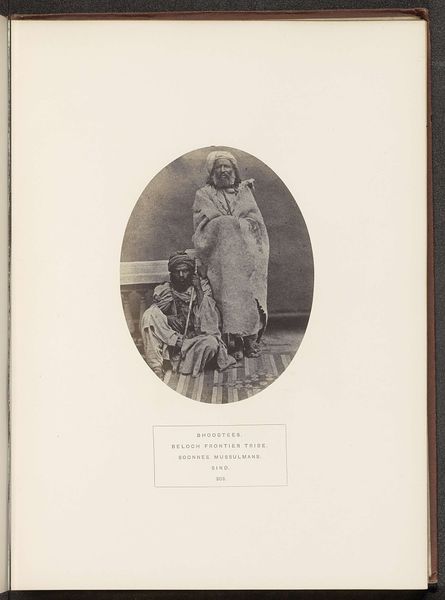

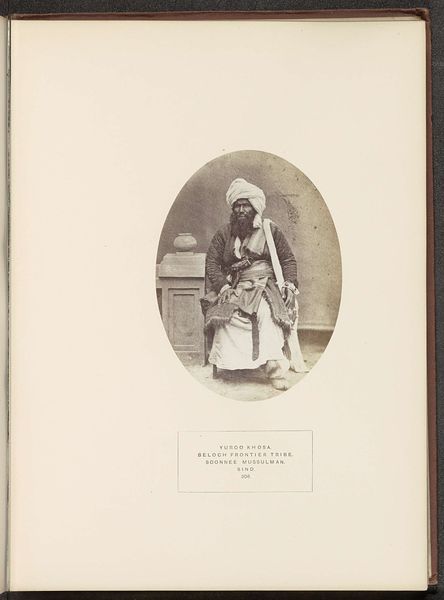

Portret van een onbekende man van de Baloch-stam in Sindh before 1872

0:00

0:00

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 128 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, hello there. Right now, we’re looking at an albumen print dating to before 1872 by Henry Charles Baskerville Tanner. It’s entitled "Portret van een onbekende man van de Baloch-stam in Sindh," which translates to "Portrait of an unknown man from the Baloch tribe in Sindh." Editor: Whoa, what a face! Those eyes… it's like he's looking right through you. There is a certain lightness with his all-white traditional garments, yet, despite the soft focus and monochrome, it feels really intense. It is like peering into history itself. Curator: The photograph offers a fascinating, albeit potentially problematic, glimpse into the ethnographic practices of the time. These kinds of images were often produced within a colonial framework, used to document and classify different populations. Tanner was part of a network of photographers who captured images that reinforced European understanding of the "Orient". Editor: Hmm, "reinforced European understanding". But look at his dignified pose. Doesn't it also feel like there’s a collaborative element? A negotiation between the photographer and subject. Look at that fierce mustache! The turban even feels a bit chef-like. Sorry, did I say that out loud? Curator: It’s important to recognize that even if there was collaboration, power dynamics were still very much at play. Photographs like this often served the purposes of empire, solidifying colonial control through representation. The circulation of images of indigenous peoples in Europe was about solidifying an understanding of difference, of "otherness." Editor: Fair point. I guess I was hoping for a kind of, I don’t know, accidental artistry? Maybe it’s my naive yearning for genuine human connection across time and cultures. Curator: Perhaps we can find artistry, or at least an unintended record of individuality, even within the problematic framework of orientalism. Thinking about the context allows us to approach it with necessary criticality and recognize its lasting impact. Editor: I am left just marveling at that face again... it feels very arresting, but in a very curious way, especially when considering what we know about the photographic intention. Curator: Ultimately, it encourages us to consider photography not just as a record, but also as a historical and social construct that actively shapes our perception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.