Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

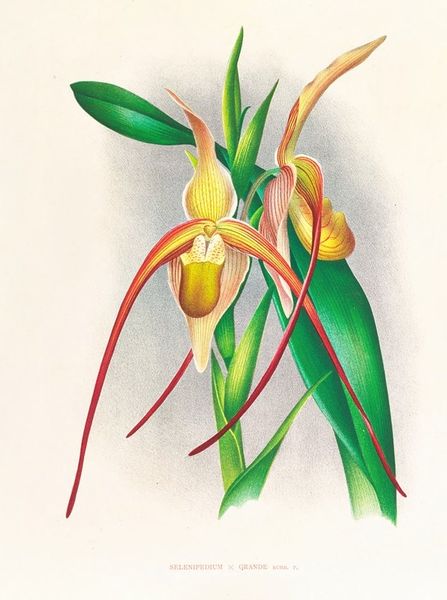

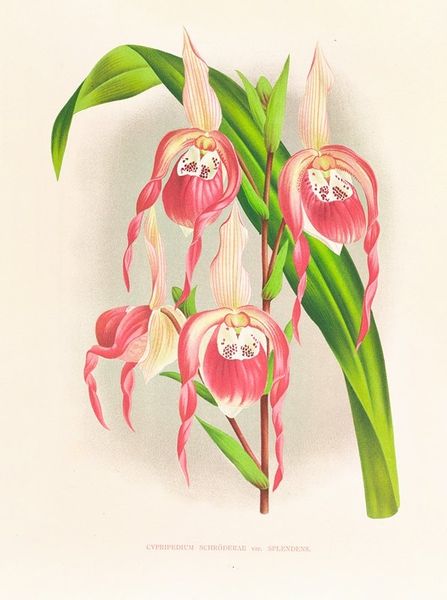

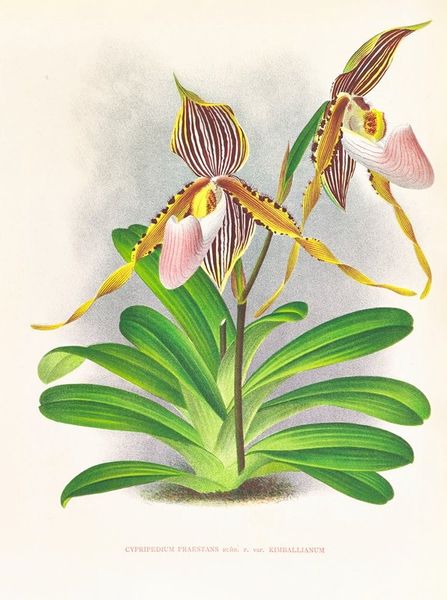

Curator: Welcome. Before us is a watercolor illustration titled "Selenipedium caudatum," likely rendered between 1885 and 1906 by Jean Jules Linden. What strikes you most? Editor: An immediate impression? The almost cartoonish droop of the petals, combined with those wildly spiraling tendrils… it gives a sense of both elegant fragility and… almost absurdity? Curator: I think you've hit on something crucial. The seemingly effortless detail achieved with watercolor points to significant artistic skill. It wasn't merely about botanical accuracy; Linden was surely influenced by the era's aesthetic preferences, possibly fueled by the exoticism associated with the plant. One can consider questions surrounding plant ownership, display, and wealth. Editor: And I think it leans heavily into very specific symbolism. Orchids are rife with cultural meaning—rarity, luxury, even eroticism, depending on the viewer and the cultural context. Look at how those cascading petals frame the central pouch; it is like the skirt of a very rare, almost unattainable thing. Curator: That ties directly to materiality, I think. How would Linden, as a visual artist, have perceived and transformed these plants for commercial means and public viewing? Watercolor lends itself to relatively easy reproduction in publications… this expands reach. Editor: Absolutely. And thinking of wider circulation, botanical art from this period was not just scientific documentation but an aspirational display of cultural capital. The detailed depiction emphasizes its otherness and perhaps its desirability in far-off lands. These are very subtle cues, that speaks to deeply embedded power structures of the time. Curator: And the format of naturalistic renderings made them very palatable for audiences. However, what sort of labor or practices could have enabled this vision, considering Linden was likely European, and these plants originate from the tropical Americas. There's tension. Editor: A valid consideration. The green backdrop is striking because it is both verdant, suggestive of life, and deliberately empty, void of real context or reference. It almost suggests that nature itself is secondary. Curator: I find it rewarding to reconsider the function and symbolism in concert with production concerns like artistic materials and the historical moment of the art’s creation. I see new richness in this work through our exploration. Editor: And for me, it's about considering those long trails as not just botanical features, but deliberate semiotic gestures designed to evoke wonder and aspiration. The orchid becomes a symbol beyond itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.