ink

#

medieval

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

ink

#

underpainting

#

china

#

line

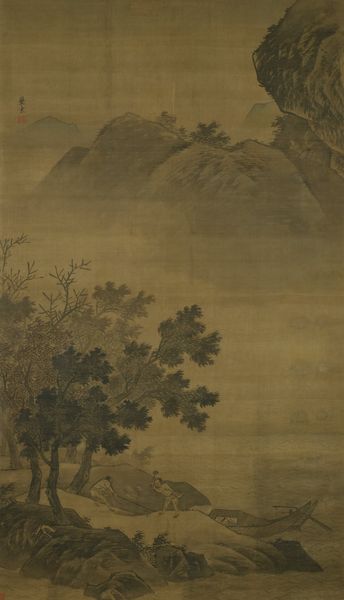

Dimensions: 65 3/4 x 41 3/16 in. (167.01 x 104.62 cm) (image)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Look at this magnificent landscape hanging before us; it's a Chinese ink painting titled "Listening to the Waterfall," dating back to approximately 1450, artist unknown. What are your first thoughts? Editor: A certain stillness pervades. The muted palette and soft lines create a sense of quiet contemplation. It feels very removed from the bustle of daily life. Curator: The anonymous artist truly captured a sense of hermetic tranquility. Waterfalls in Chinese painting are often visual metaphors for the Dao, a symbol of ceaseless transformation. It reminds one of our constant need to self reflect through contemplation. Editor: I agree, the presence of the waterfall as a source of spiritual metaphor is undeniable. Water motifs recur across time, often serving the ideological functions demanded of painting in a given period. In this piece I imagine that is part of its cultural draw. Curator: Indeed, the Daoist concept of living in harmony with nature is very important. The human figure seems purposefully diminished in scale in relation to the natural landscape. Editor: It’s interesting to think about the intended audience and context of such works. I wonder where this was hung, or under what circumstances it was originally viewed. What messages of power might it subtly be reinforcing? Or was it purely for aesthetic enjoyment, this feeling of closeness to nature? Curator: Perhaps it’s not so binary. Paintings like this could function on multiple levels; both reaffirming social values, but providing the mental space for individuals, especially elites, to imagine alternative modes of being. Either way it holds such a profound quality and meditative power that it has affected generation after generation. Editor: A duality of both, yes. Its survival, and display, speaks to an enduring desire. Curator: It makes one wonder how this particular painting survived. So much is now lost forever. It stands today, reminding us that our existence is so miniscule when looked at from a geologic perspective. Editor: Its survival serves as an encouragement to the pursuit and contemplation of visual artifacts as echoes from history, across a bridge of signs and aesthetics.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

In this evocative early Zhe school painting, a scholar-recluse lying near the edge of a cliff listens to the powerful waterfall that roils and boils above his resting place and crashes into the crevasse below. He has set aside his qin (zither) and book to enjoy the natural environment around him. The style and theme of this painting derives from the work of Ma Yuan (active 1180–1225), a well-known Song dynasty artist whose style had tremendous influence on Zhe school painting throughout the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The qin-playing recluse enjoying a waterfall is one of the most popular themes in Zhe school subjects. The painting underscores the early Ming revival of Song dynasty (960–1279) painting. Looking back on this golden age of Chinese culture was a way of negating the artistic accomplishments—which were many—of the Yuan dynasty (1280–1368), a period of Mongol control.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.