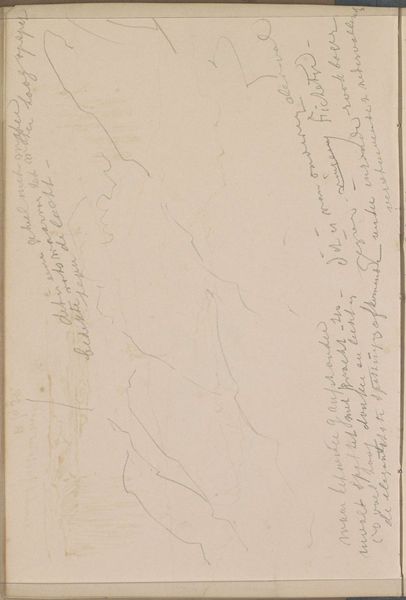

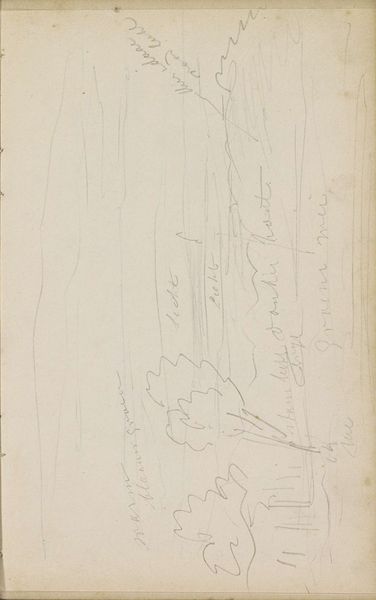

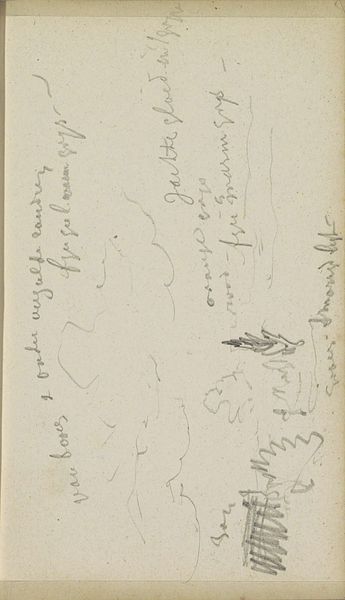

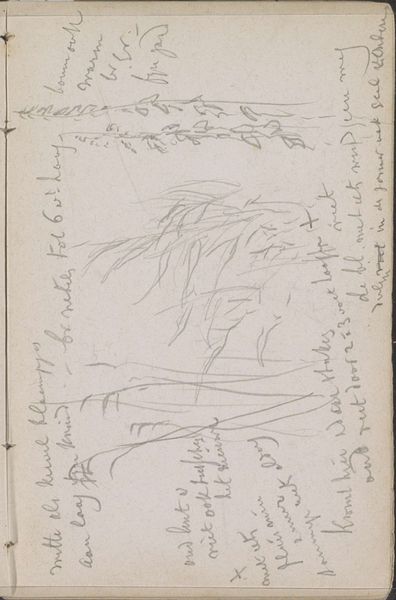

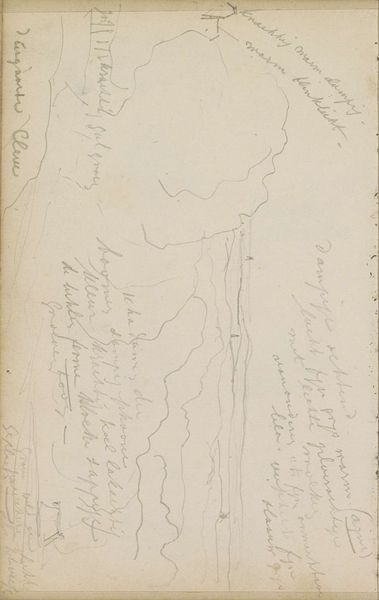

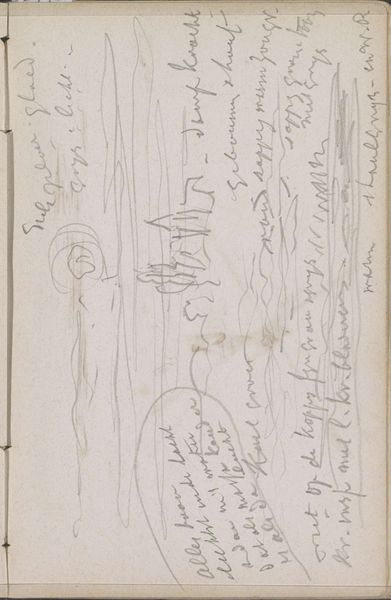

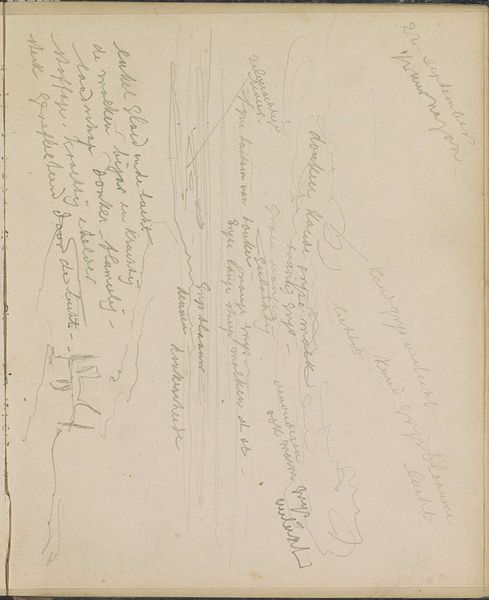

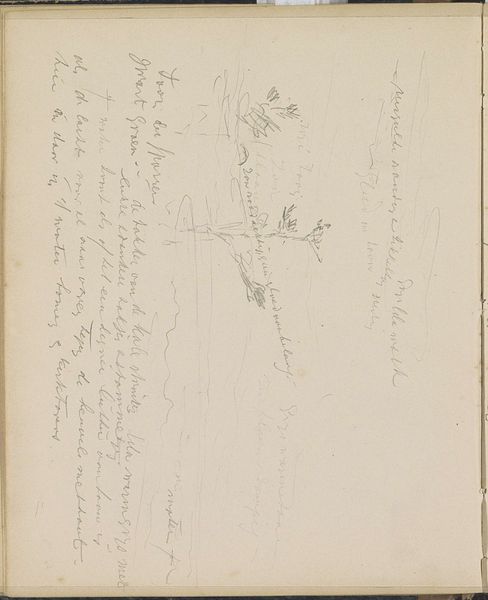

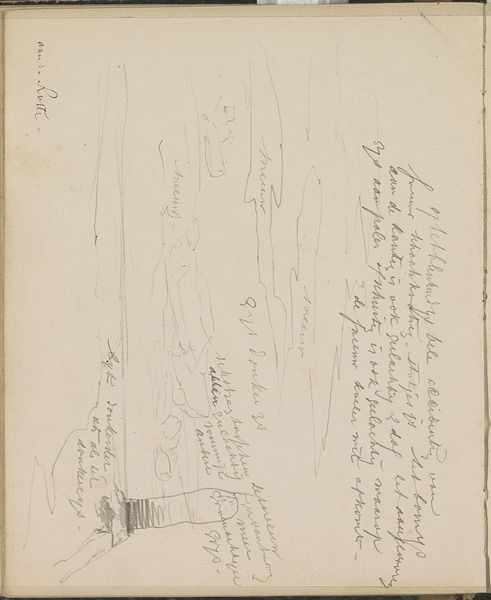

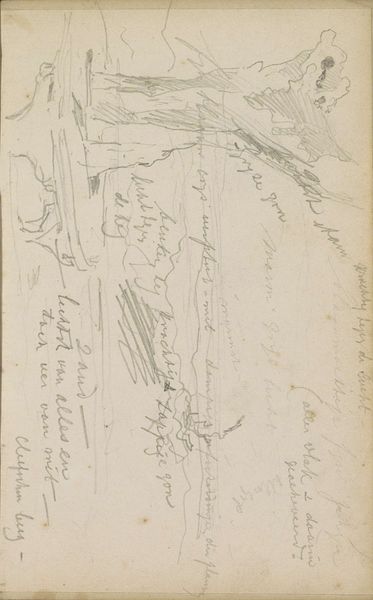

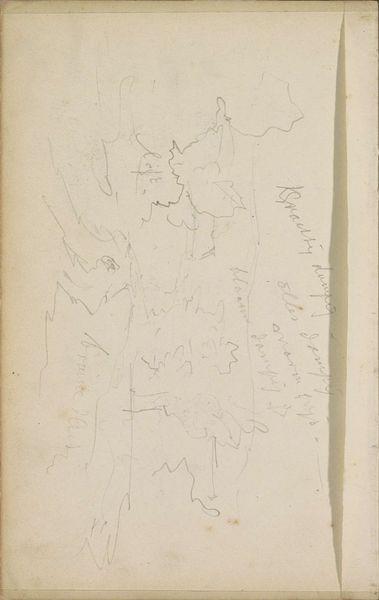

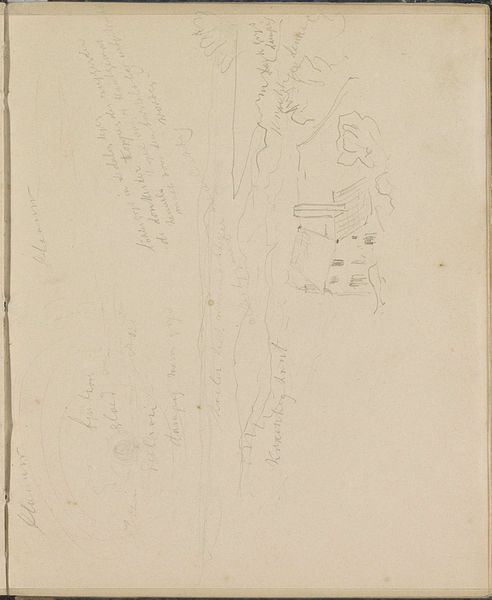

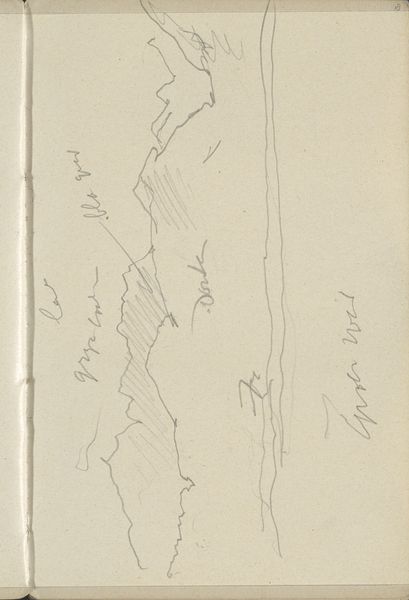

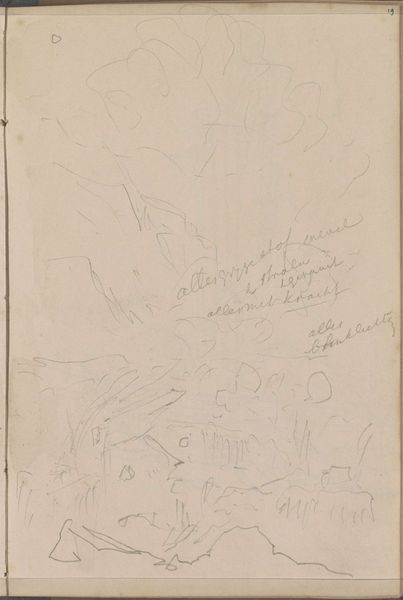

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

waterfall

#

paper

#

pencil

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Tavenraat’s “Waterval,” a pencil drawing on paper from 1858-1859, feels very immediate. You see the waterfall, yes, but the eye is drawn into these notes scribbled across the image. The work appears to be equal parts sketch and documentation. What draws your attention? Editor: I'm struck by the seemingly casual nature of the materials. It's just pencil on paper, like something I might do in a sketchbook. It makes me wonder, though, about the relationship between this kind of everyday process and the tradition of landscape art. Does that material simplicity change how we view the final artwork? Curator: Absolutely. Consider the labor involved in producing art materials during the mid-19th century. Pencils weren’t always mass-produced; think about the process of mining graphite, preparing the wood… This piece highlights a specific stage in art production, revealing the artist’s labor and choices. Is Tavenraat elevating the mundane by sharing what typically would remain unseen? What assumptions did 19th-century viewers hold about drawings versus more “finished” oil paintings, and what social classes could afford each material? Editor: So, by using such basic materials, Tavenraat might be democratizing landscape art in a way? Making it accessible both in creation and in subject? Curator: Precisely. He disrupts the hierarchy between 'high art' and more accessible forms of image-making. His focus becomes the direct interaction between the artist, the natural world, and the means of representation. He asks us to contemplate all aspects of art creation, not only the finished piece in a gilded frame. Editor: That makes me think differently about all the preliminary sketches I see in museums, and what they tell us about the economics of art production at the time! Thanks for clarifying the way materials shape the work's meaning and relevance!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.