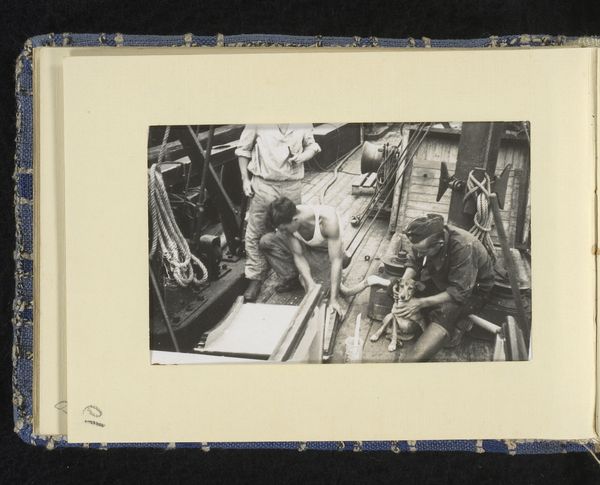

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

print photography

#

black and white photography

# print

#

social-realism

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

modernism

#

realism

#

monochrome

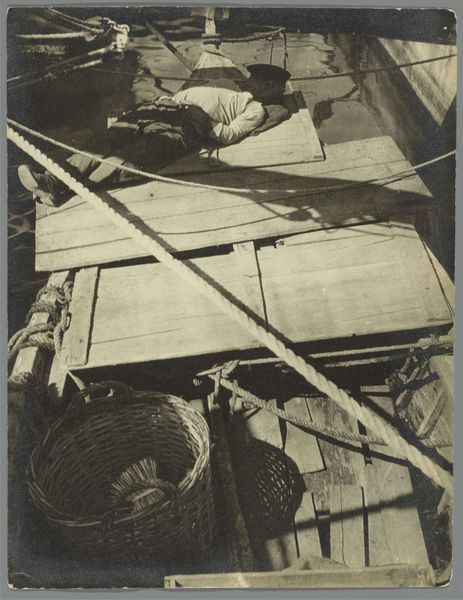

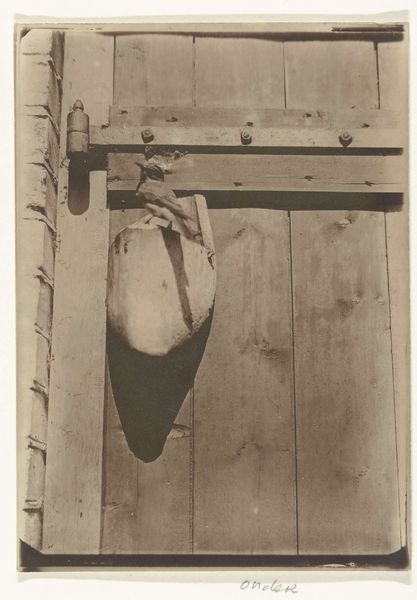

Dimensions: width 19.5 cm, height 18 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's take a look at "Twee havenarbeiders lossen een vrachtschip," which translates to "Two Dockworkers Unloading a Cargo Ship," a gelatin-silver print made sometime between 1940 and 1950, currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. It was created by A.B.C. Press Service. Editor: Wow, it feels like looking into the past. You know, like stumbling upon a grainy memory in an old photo album. The scale of those sacks, you can almost feel the weight of them. What's your take? Curator: For me, this image speaks volumes about the representation of labor in the mid-20th century. There’s an element of social realism that is worth noting; we are witnessing workers—specifically men—performing their job in the shipping industry. This kind of imagery, particularly in a period marked by economic instability, reflects shifting ideas about identity and masculinity. Editor: Right, right, it definitely romanticizes the… grunt work. But the composition is so tight, almost claustrophobic, with those massive sacks towering over the men. The high angle… I almost feel seasick looking at it! Curator: That angle perhaps intends to frame the workers’ existence—trapped—within the capitalist framework, to be utilized and consumed for labor power. What I find striking is how the work obscures the identity of each individual; class is what defines them here. Editor: I dig that. There's no individuality here—they're practically swallowed by the sheer magnitude of the industrial landscape. They seem anonymous, archetypal. It hits you in the gut. And that monochrome effect really heightens that feeling. What are your thoughts? Curator: In light of our current socio-economic climate, photographs like these offer us the possibility to investigate labor inequities, gender performance, and also challenge assumptions and expectations surrounding both of them. It serves as a moment for pause and reflection, no? Editor: Absolutely. It's more than just an image of labor. It's an image about how we *think* about labor. A pretty cool commentary on the past... and maybe even our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.