Gezicht op het paviljoen van Léopold Koenig Junior op de Wereldtentoonstelling van 1885 in Antwerpen before 1885

0:00

0:00

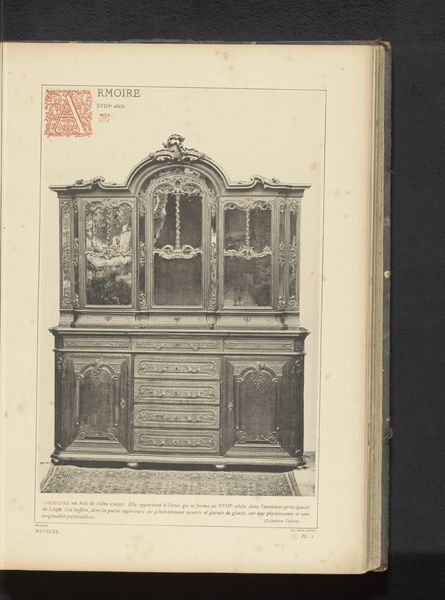

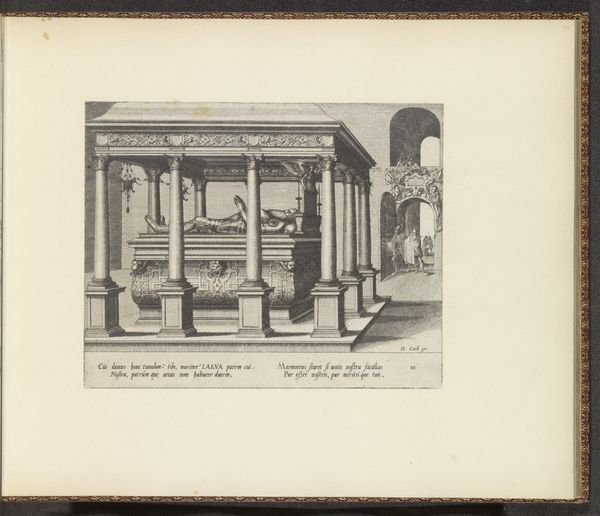

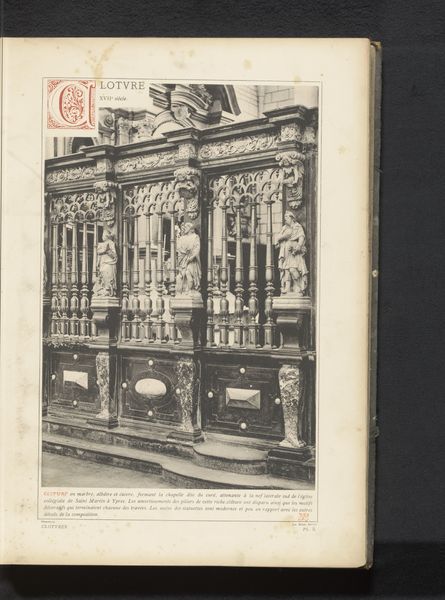

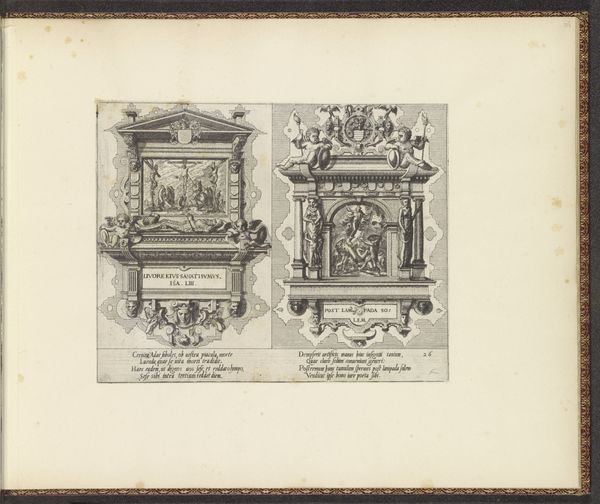

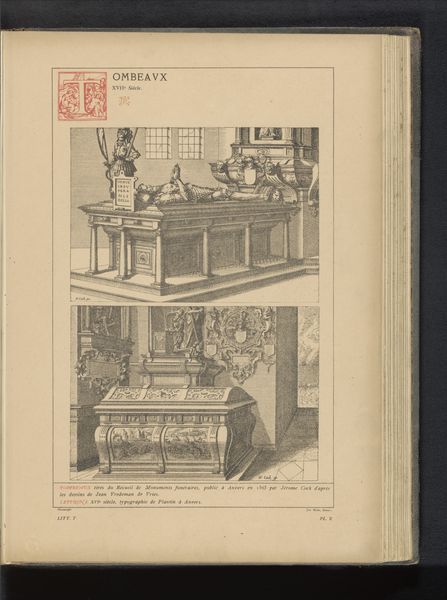

print, photography, engraving, architecture

# print

#

photography

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 267 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving, I feel like I've stepped into a grand hall, but a silent one. It has an aura of faded glory about it, almost a theatrical stage set. Editor: It's fascinating, isn’t it? What we’re seeing is a photographic reproduction of an engraving depicting Leopold Koenig Junior's pavilion at the 1885 World Exhibition in Antwerp. These exhibitions were about showcasing progress, trade, and frankly, colonial power. Curator: Progress… it’s interesting how “progress” often feels so hollow when it’s just about showing off, like an overripe fruit on display. Look at the lettering across the top, beautiful but completely foreign to me! And the sheer volume of stuff in the display cases—what do you even call that architectural style? Editor: Well, the lettering would be Russian, which helps place Koenig, a St. Petersburg merchant. As for the style, it's a blend—eclecticism reflecting the late 19th-century impulse to incorporate different influences and showcase the globe’s bounty. But I’d argue the “style” is fundamentally about power structures. Curator: Power dressed up as… curiosities? Makes me think of Marie Antoinette playing shepherdess. Editor: Exactly. These pavilions, showcasing advancements, also masked inequalities. Who got to participate, and whose resources were being displayed? It's a window onto a very specific, very biased worldview. Think about the resources invested here, compared to social reforms. Curator: And all for what? Now it's a faint, ghostly print, like a half-remembered dream of a bygone era of industrialists! But looking closely… doesn't the building itself look precarious, almost as if it’s made of playing cards, stacked ever so delicately on top of each other? Editor: In many ways, that's an astute reading, particularly when we understand these global displays for what they are—fragile, constructed narratives, obscuring as much as they reveal about resource exploitation, industrial labor, and inequality. They were more ephemeral than anyone cared to acknowledge. Curator: So, a Potemkin village of progress! I feel like my initial sense of theatricality has been affirmed. Thanks to Leopold Koenig Junior and this long lost photograph for reminding us that these shiny buildings aren't nearly as solid as they look! Editor: Indeed, questioning whose stories and achievements are memorialized through artwork is, in its own way, a form of progress too. This print is both an artifact of and a testament to how we might continually re-evaluate that progress.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.