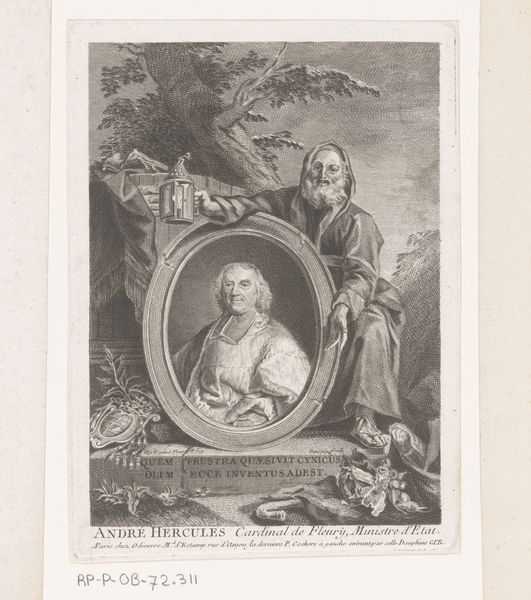

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 244 mm, width 171 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

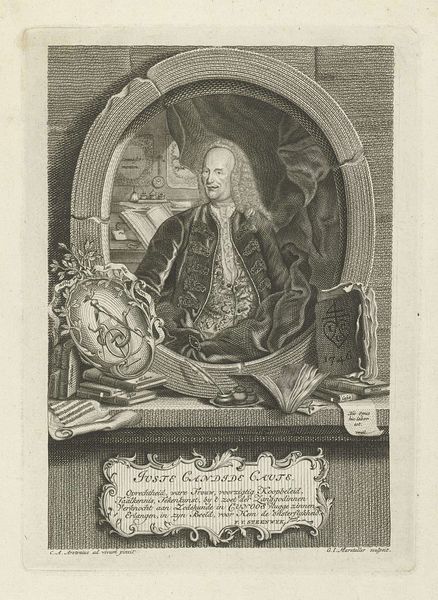

Curator: I’m struck by the stoicism radiating from this portrait—a sort of austere self-possession. Editor: That’s interesting. This is an engraving, "Diogenes bij een portret van André-Hercule de Fleury," likely created between 1708 and 1780. Jacob Houbraken is the artist. What are you keying into here? I mean beyond the portrait itself? Curator: Look at the figure of Diogenes. See how he's holding the portrait? It's an incredibly potent symbol. Diogenes, forever searching for an honest man. He stands here almost as an endorsement of Cardinal de Fleury. The lantern implies the Cardinal is, finally, that honest man. The weight of that archetype! It is all commentary on power, morality, and the role of the Church within French society during the 18th century. Editor: Yes, the lantern is a very traditional symbol but its purpose is being subverted. Here, the symbolism is inverted, used to validate authority instead of questioning it. Is the artist commenting on Fleury or Diogenes, I wonder? It makes me think of later critiques leveled against power structures during and after the French revolution, and how Fleury may be cast here as enlightenment’s answer to an honest broker, instead of what? Some other ideal of masculine honor? Curator: Perhaps! This is where context truly enriches our viewing. De Fleury held significant positions, from tutor to Louis XV, to a Cardinal and a chief minister. These affiliations would affect contemporary interpretation as the viewers engage with the idea of seeking and finding virtue in leadership. But it brings up many more questions about whose virtue is being examined. I suppose we can continue to explore how portraits can tell stories, even become cultural artifacts representing shifting societal values, in other rooms. Editor: Indeed, art constantly reframes our values, never allows us to truly rest in certainty.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.