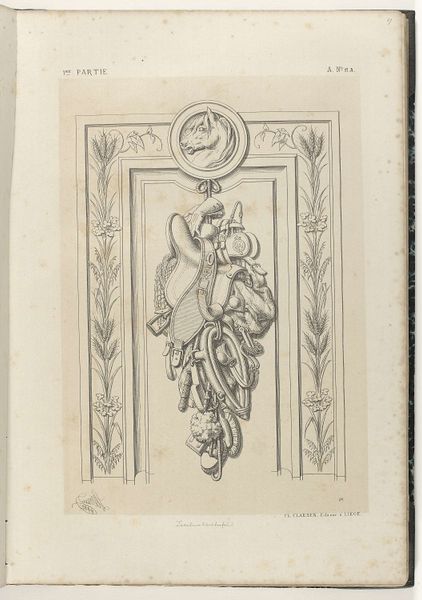

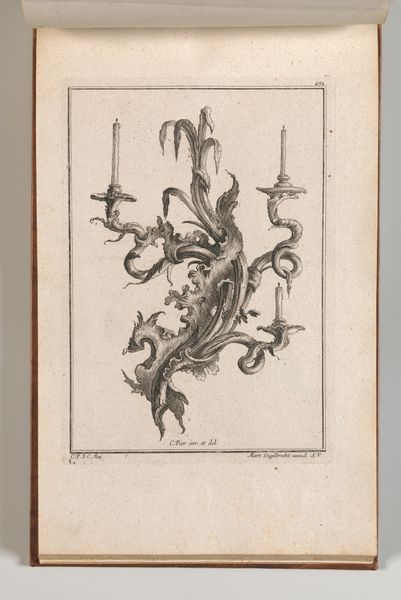

Dimensions: height 278 mm, width 184 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Gottlieb Friedrich Riedel's "Trofee met helm en schilden" from 1779. It's a print, I believe made of metal and using engraving. It feels quite imposing with all these instruments of war arranged so meticulously. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This print offers a glimpse into the visual culture of the late 18th century, a time steeped in the legacy of conflict and the visual language of power. Trophy imagery like this served not merely as decoration but as potent reminders of military achievements, social standing, and the perpetuation of hierarchical structures. Notice how the assembled armor and weapons aren't simply thrown together. They are strategically arranged to create a composition that conveys both strength and artistry. The presence of the helmet and shields suggests a clear reference to the art of warfare and nobility. Editor: So it’s less about celebrating a specific victory, and more about reminding viewers of existing power structures? Curator: Precisely. Consider the Baroque style informing its creation. Baroque, in its very essence, sought to overwhelm and impress. How do you think that aesthetic intersects with the political and social functions of this artwork? Who do you imagine the intended audience was for such a print? Editor: Someone of wealth, probably connected to the military, looking to signal their status. This image seems almost like propaganda, but for a very specific, elite audience. Curator: That’s a keen observation. In examining such images, we gain insights into the values and aspirations of specific social groups at a given moment in history. Images can have a direct and meaningful role to the intended and unintended viewers and participants. Editor: It’s fascinating how a seemingly decorative piece can reveal so much about the society that produced it. I’ll never look at trophies the same way again. Curator: Indeed, questioning the motivations behind images is fundamental to understanding their broader cultural and historical significance. There is always more under the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.