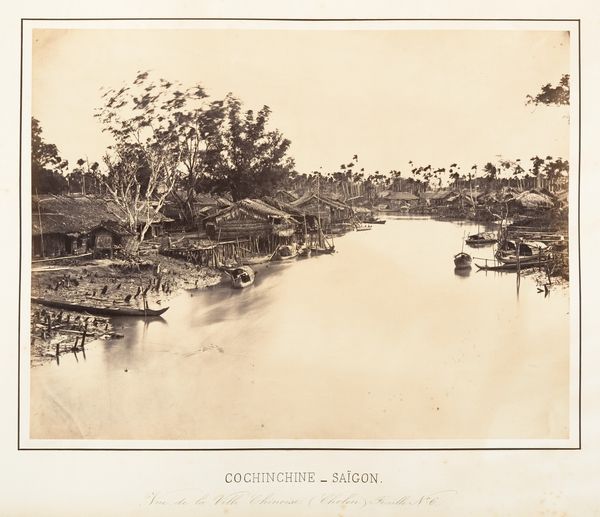

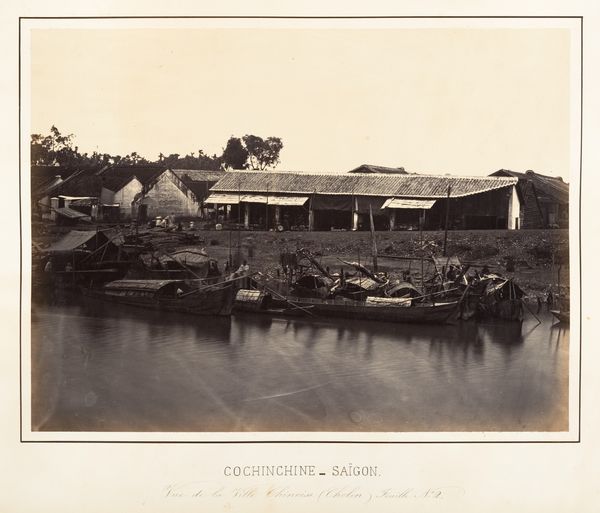

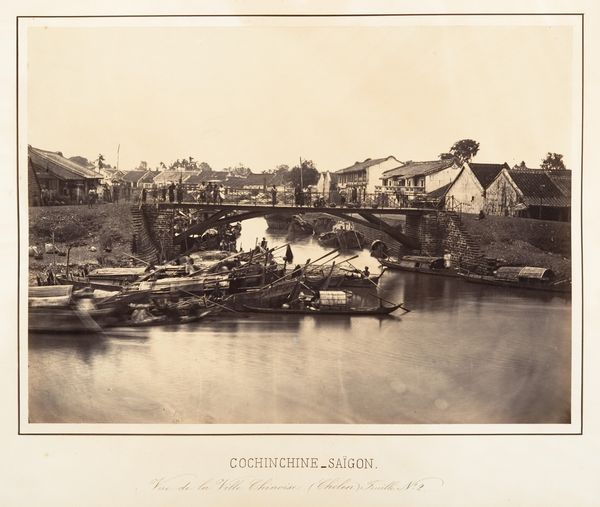

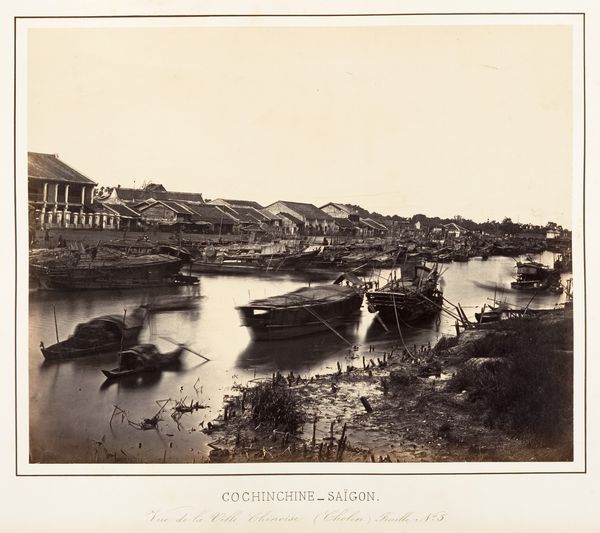

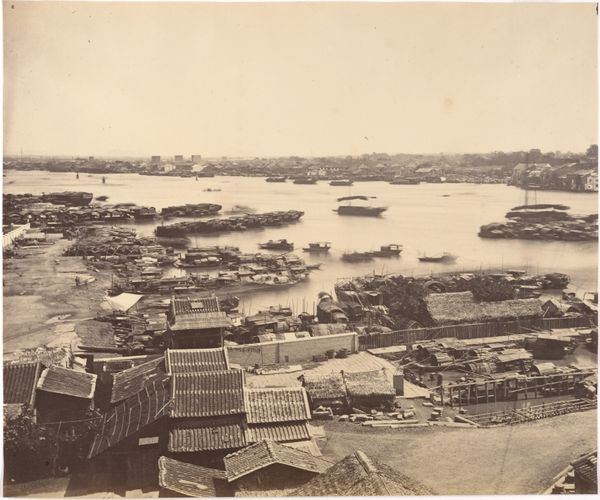

Vue de la Ville Chinoise (Cholen) Feuille No. 3, Saïgon, Cochinchine 1866

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

boat

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: 22.3 x 30.1 cm (8 3/4 x 11 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

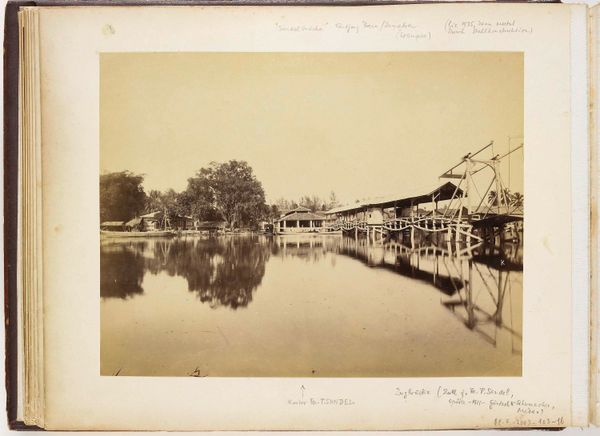

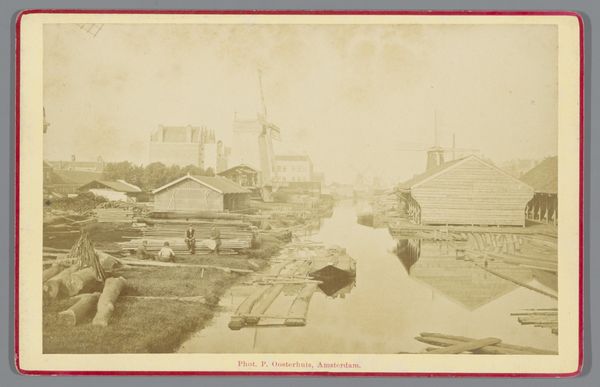

Curator: Looking at Emile Gsell's 1866 gelatin silver print, "Vue de la Ville Chinoise (Cholen) Feuille No. 3, Saïgon, Cochinchine," what's your immediate reaction? Editor: A hush. It's the kind of image that makes you quiet. The light is so still, almost sepulchral, reflecting off the water and rendering the houseboats near ghostly. You can almost hear the quiet lapping of water against the wooden hulls. Curator: It’s a remarkably evocative photograph, isn’t it? Gsell, working in what was then French Cochinchina, captured a slice of life in Cholen, now part of Ho Chi Minh City, through the lens of orientalism. What’s compelling is seeing how early photography was deployed to document and, arguably, define a colonial space. Editor: Exactly! And you feel that tension between documentation and… exoticization, if that’s a word. It reminds me of old postcards. You wonder what he left out of the frame. Is there anything deliberately omitted from the picture? I would really want to know more about the people, not just the location, or architecture. Curator: That’s precisely what the image sparks, isn't it? The desire to peel back the layers and engage with the unseen narratives of the Cholon residents of that era. Consider that Gsell’s work circulated widely in Europe, shaping perceptions and fueling colonial fantasies. Editor: You can almost imagine them receiving that image, unable to even point at this place on the map! How powerful images are… I guess what I’m taking away most is the deceptive stillness – the layers of history simmering just below that mirrored water. And that's the quietest kind of revolution, I guess. Curator: I think your insights on the interplay of visibility, representation, and colonial power add new layers of complexity to this 19th-century photograph, revealing both the charm and the embedded assumptions it carries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.