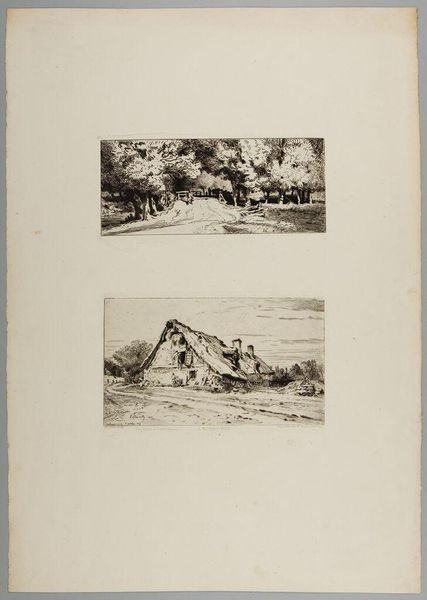

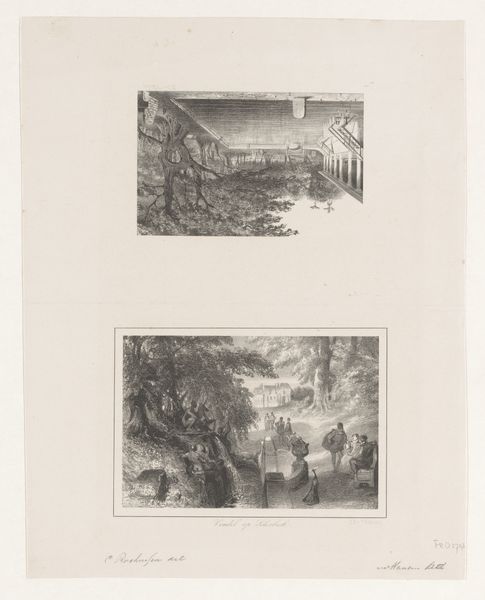

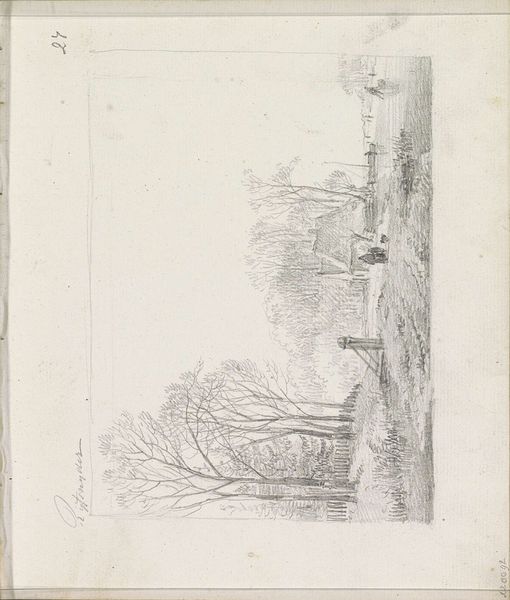

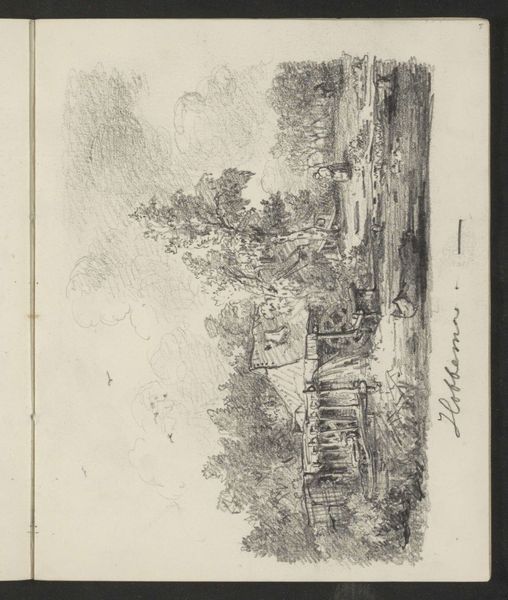

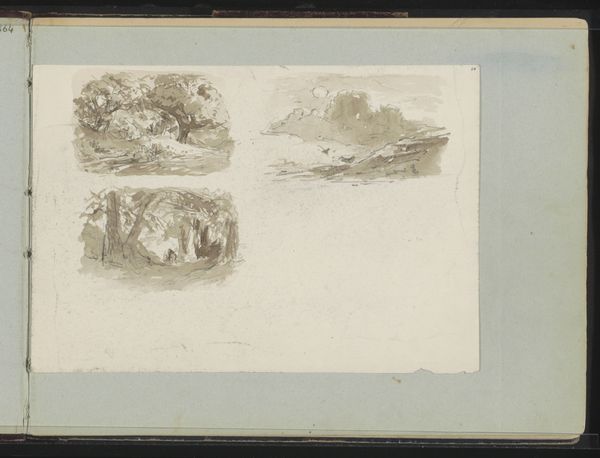

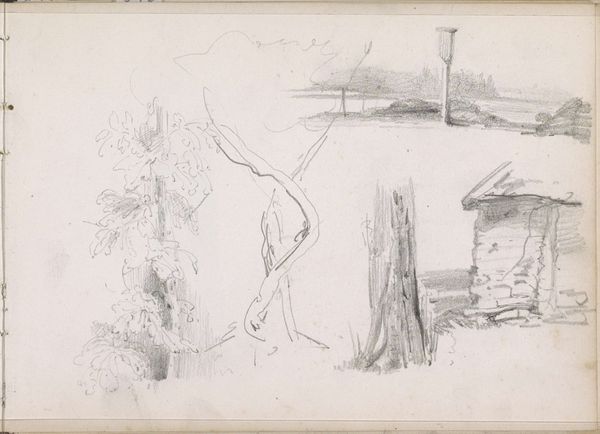

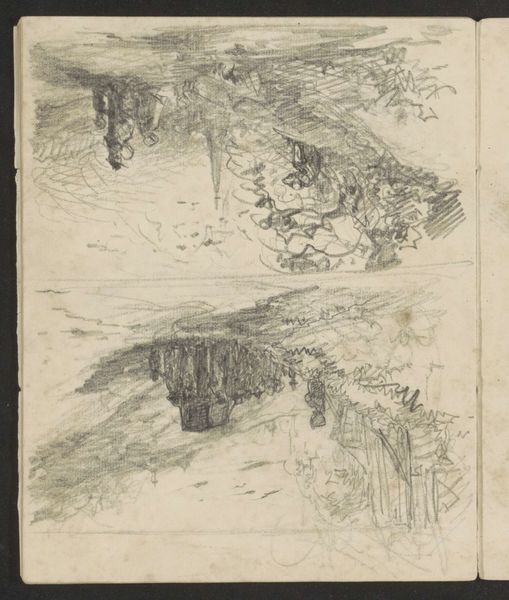

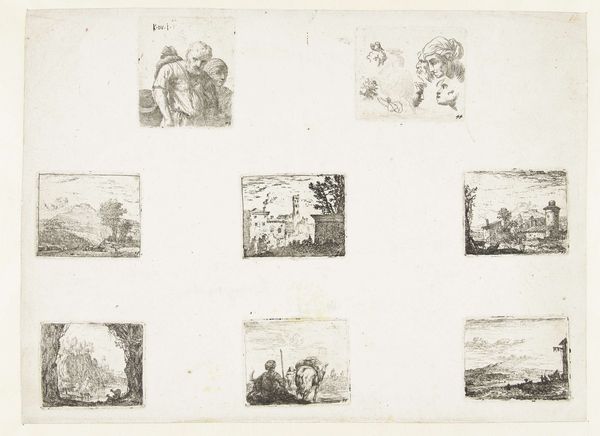

Rivierlandschap met een boom, een berglandschap en mannenkoppen, een molen en dieren c. 1826 - 1888

0:00

0:00

drawing, plein-air, paper, watercolor

#

drawing

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

mountain

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's delve into this sketchbook page by Johannes Antonius Canta, dating from approximately 1826 to 1888. It’s rendered using watercolor and coloured pencil on paper and contains landscape elements, studies of human heads, and some animals. Editor: It’s certainly evocative. A melancholic study in browns and greys dominates the piece, punctuated by the darker sketches and the ambiguous mass of figures. The watercolor application feels spontaneous and quite dreamlike. Curator: Absolutely. The style reflects the period's interest in capturing nature en plein air. This shift was, in part, fueled by social and cultural shifts around Romanticism’s reverence for nature, away from the rigid academic landscapes, allowing for a democratization of art as it could be created anywhere. Editor: That rings true. The arrangement itself, these vignettes sharing the same page, emphasizes the subjective experience. One senses Canta isn’t merely representing landscapes, but engaging in a kind of self-exploration, probing into identity and emotion through his drawings. How do you think this selection interacts with broader ideas of the natural world at the time? Curator: Canta might be hinting at the power structures imbedded in even the 'purest' representations of landscapes; remember, those idyllic rural scenes were often backdrops for brutal systems of labor and land ownership, deeply intertwined with class and gender disparities. Perhaps his superimposition hints at his own interrogation? Editor: That is a powerful and thought-provoking reading. I also believe his technique subtly questions authority. The loose watercolor washes feel incredibly transient; they don’t solidify nature into a single, imposing view but reveal its changing, ephemeral qualities, offering alternative and ever changing views of nature to the patriarchal gaze, if you will. Curator: I hadn't considered that connection so explicitly, but now that you mention it, the subversion feels palpable. Editor: It adds layers of interpretation, certainly. So, where do you think Canta's intent leaves us then? Curator: He prompts us to consider not only our gaze upon nature, but its relation to broader social and political structures that still shape our perceptions. Editor: Indeed. An unassuming page holds volumes when we consider the power dynamics and philosophies that sculpt how we see.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.